Image: Shutterstock

Growing a Small Nonprofit Can Be a Bit Like Adolescence — Painful, Difficult, Awkward

Read this article in

Anyone who has interacted with a teenager, or remembers having been one themselves, knows the challenges of adolescence. It’s a period of change and growth, when we figure out who we are. That journey can be painful and difficult.

When it comes to nonprofits, that period of transition can be similarly awkward, trying to find what your organization ultimately stands for, what its ambitions are, and how to grow from fledgling start-up to a robust organization that is set up to succeed.

That’s the phase we’re going through at the Global Reporting Centre, a small nonprofit organization based in Vancouver, Canada, that grew out of a desire to change how global journalism is practiced.

Having both worked for decades in mainstream media, and having come from diverse backgrounds — Klein the son of refugees, Crossan raised by her First Nations grandmother — we saw a need to challenge what we saw as problematic norms and practices in international reporting.

Instead of parachuting into far-off places for short visits, we empower marginalized communities to tell and own their own stories. Instead of working with local journalists relegated to subservient roles as “fixers,” the center partners with reporters around the world. Instead of going to scholars for quotes to bolster reporting, we bring experts into the newsroom from the start.

The center began with two part-time employees, as a side project alongside Klein’s other duties as a professor at the University of British Columbia. Close to a decade later, we now have three full-time staff members, two part-time. But despite a body of award-winning work and meaningful impact, our small team’s endless efforts to “punch above our weight” are not sustainable. It’s also difficult for a small organization to represent the breadth of backgrounds and perspectives necessary to tackle global stories. The GRC has recently been formalized as a center at the university, but we’ve come to realize that, if it has any chance of survival — to make that leap from “adolescence” to “adulthood” — we need to grow.

The landscape for journalism nonprofits has become more precarious, with major foundations pulling back from journalism funding, donor fatigue setting in after years of crisis-driven fundraising, and the politicization of philanthropy creating new pressures. At the same time, the need for independent, innovative journalism has never been more urgent. Against this backdrop, the questions we face are familiar to many journalism nonprofits today: what’s that optimal size, and how do we get there?

Looking for Successful Models

In the for-profit startup world, there’s a long history of fledgling organizations getting a leg up from early investors, and then either flourishing or dying. While nonprofits operate under fundamentally different constraints and measures of success, the startup ecosystem offers valuable lessons about scaling organizations and securing early-stage support.

“I’ve always believed that you have to take a business approach to philanthropy,” said Frank Giustra, founder of both for-profit ventures like Lionsgate Entertainment, nonprofits like the Social Enterprise Partnership, and a recent donor to the GRC. “You have to show results and find ways to evaluate your results.”

But in the nonprofit ecosystem, the motivations and outcomes are bespoke.

“The metrics that matter in a for-profit are financial returns,” noted Paul Cubbons, a business professor at the University of British Columbia. “The metrics that matter in a nonprofit are actually about mission alignment and impact.”

When it comes to nonprofits, “using the word investor is a misnomer,” explained Oliver Hamilton, a legal and management consultant. “An investment is something tangible you’re going to get compensation out of, which flies in the face of donations.”

This poses one of the fundamental challenges in funding a nonprofit — how to show success, and gain the backing and trust of supporters. On this, we were told time and again that it’s the people running the show that make a key difference.

“I always start with — who’s managing this and how are they capable of making something happen?” said Giustra.

Cubbons agreed: “Everything I’ve learned in fundraising, whether nonprofit or for-profit, is that it’s all based on developing relationships.”

The problem for a small organization can be getting a foot in the door. All too often, donors invest in larger, more established organizations with whom they have long-standing relationships.

Risk aversion has become even more pronounced in recent years — and in an era of economic uncertainty and a growing political divide, the handful of well-funded journalism centers with ample staff and walls full of awards attract the lion’s share of support from traditional backers. For smaller, more experimental organizations, the path to sustainability has become steeper.

“Part of my frustration with philanthropy is the framing of ‘prove up your value, prove up your worth,’ and these are the hurdles or the litmus tests we use to see if you’re ready for additional funding,” said Lawanna Kimbro, managing director of Stardust Fund, a small family foundation out of Texas, which has supported the GRC in the past.

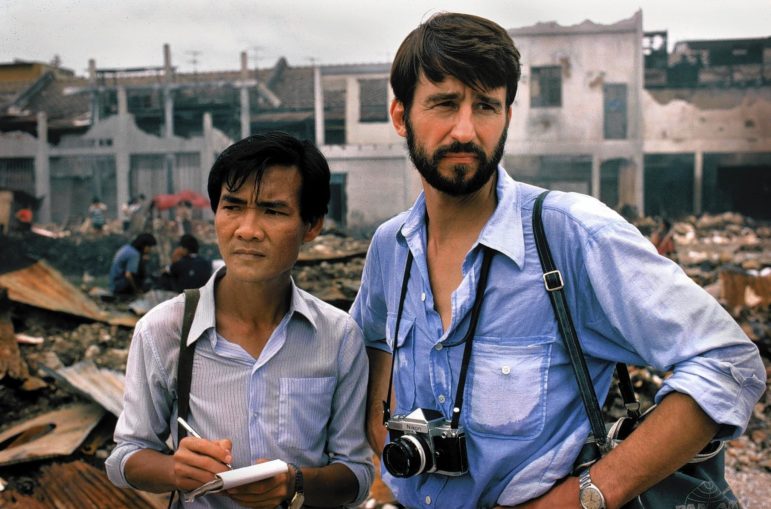

GRC Executive Director Andrea Crossan reporting in Paris in December 2023. Image: Courtesy of the Global Reporting Centre

She argues that this just reinforces the status quo, leaving little capacity for supporting those who are experimenting, or organizations led by traditionally marginalized groups.

“The other perversion in this is that money begets money. So much of what people are counting is whether or not someone can afford a development officer or a grant writer, not per se whether or not it’s efficacious,” she continued. “We undercapitalize people and use their small coffers as reasons not to give them more.”

At the center, most of our success in fundraising has been through smaller family foundations and individual philanthropists, who are often more willing and able to take risks.

We have also diversified our funding, through non-traditional supporters like academic agencies. For instance, a US$2.5 million grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) in 2018 gave us the runway we needed to build a supply chain reporting initiative, and we used this funding to leverage matching support from foundations.

Kathy Im, who heads up the journalism program at the MacArthur Foundation, appreciates the importance of giving organizations the space and time to find themselves, and in a co-authored essay for American Press Institute, she made the bold case for unrestricted funding for journalism nonprofits, particularly those starting out and taking chances.

She gave the concrete example of the Investigative Reporting Program based out of UC Berkeley, which had a tip about sexual assault of farmworkers, but didn’t have funds to pursue this story further. When MacArthur gave the program US$2.5 million in unrestricted funding, a small portion was used to chase this lead, which resulted in an award-winning and policy-changing documentary for FRONTLINE. “Without those funds,” Im wrote, they “would not have been able to pursue this story. Decades of farmworker abuse might have continued unnoticed and unabated.”

The power of unrestricted funding becomes even clearer when it enables genuine innovation. A benefit of doing independent journalism without the pressures of profit and circulation is the ability to experiment. One example is an approach to reporting we call “empowerment journalism,” in which we hand storytelling power over to story subjects. This departs from traditional newsroom standards of maintaining editorial independence and control. But as a result of these rules, marginalized communities are often misrepresented, or ignored altogether.

We have been able to crowdfund and secure academic funding to experiment with this new model, and produced an eight-part series, Turning Points, on alcohol use, addiction, and healing in Indigenous communities for PBS NewsHour, in which the Indigenous storytellers directed their own short documentaries. The series was awarded a national Edward R. Murrow Award for Excellence in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.

Image: Academic Director Peter Klein, reporting from the field in Yellowknife, Canada, for GRC’s award-winning eight-part series, Turning Points. Image: Courtesy of the Global Reporting Centre

This kind of innovation requires resources — not just to experiment, but to have the organizational capacity to take risks. For us, growth isn’t about empire-building; it is about having enough staff to pursue ambitious projects while maintaining quality, and enough diversity of perspectives to tell global stories responsibly.

The latitude we had to try new approaches has, in the end, helped us ultimately sharpen our message to funders — and better define our purpose. In startup mode, organizations tend to take on any projects or funding that crosses the transom. This can overcommit an already stretched staff, and can soften the focus of an organization — and we were certainly guilty of this in our early years. As we mature, we have started to reject projects, and even turned down smaller grants with long lists of deliverables that do not align well with our mandate.

The adolescent phase taught us crucial lessons. First, that sustainable growth isn’t about becoming a different organization — it’s about having sufficient resources to fully realize your mission. Second, diversified funding from “venture philanthropists,” family foundations, and non-traditional sources like academic grants can provide the flexibility that risk-averse major foundations cannot. And third, that saying no to misaligned opportunities is as important as saying yes to the right ones.

Today’s journalism nonprofits face these same growing pains in an even more challenging environment. But the organizations that will thrive are those willing to experiment, to cultivate diverse funding relationships, and to stay true to their mission even as they scale. Every adolescence is awkward — but it’s also when we discover our true capabilities.

Peter Klein is founder and academic director of the Global Reporting Centre (GRC), a former producer at 60 Minutes, former executive editor of NBC News.

Peter Klein is founder and academic director of the Global Reporting Centre (GRC), a former producer at 60 Minutes, former executive editor of NBC News.

Andrea Crossan is the executive director of the GRC, and former executive producer of the public radio program The World.

Andrea Crossan is the executive director of the GRC, and former executive producer of the public radio program The World.