The Global Backlash Against NGOs (and How To Fight Back)

Authoritarian governments have cleverly used the liberal norm of transparency in order to shut down liberal groups in their countries, a new report has detailed.

The report, “Distract, Divide, Detach: Using Transparency and Accountability to Justify Regulation of Civil Society Organizations,” is aimed at helping civil society organizations (CSOs) against a growing backlash against them. The report describes how a focus on transparency, in particular requirements to disclose sources of funding, has allowed authoritarian states to paint liberal CSOs (also known as NGOs, non-governmental organizations) as puppets of the West with little local constituency, and to justify crackdowns against them.

The report, “Distract, Divide, Detach: Using Transparency and Accountability to Justify Regulation of Civil Society Organizations,” is aimed at helping civil society organizations (CSOs) against a growing backlash against them. The report describes how a focus on transparency, in particular requirements to disclose sources of funding, has allowed authoritarian states to paint liberal CSOs (also known as NGOs, non-governmental organizations) as puppets of the West with little local constituency, and to justify crackdowns against them.

The most notorious example is Russia’s so-called “Foreign Agents Law,” which requires groups getting funding from abroad to register and tar themselves with that unattractive label. But that is just one example of many similar cases around the world, and especially in the post-Soviet space.

The report also cites Azerbaijan as an exemplar of the trend.

[T]he government of Ilham Aliyev invoked transparency when legislation to regulate CSOs was introduced. In 2013, the government stated at a UN forum that its NGO legislation “should only disturb the associations operating in our country on a non-transparent basis.” The actual legislation reached far beyond transparency, as the bank accounts of most CSOs were frozen. Many CSOs closed, and others could restart operations only after demonstrating loyalty to the government. Several human rights defenders were arrested and held in prison for months, some of them under charges of tax evasion and fraud related to their CSOs. Most independent observers viewed the charges as fabricated.

The governments use the transparency argument in bad faith, argues the report’s author, Tbilisi-based Hans Gutbrod.

“Many of the arguments on transparency and accountability appear reasonable at face value: Governments appear to ask of CSOs, in many cases, what CSOs ask of governments,” Gutbrod writes. “[A] degree of regulation to ensure that these are organizations working for broader charitable purposes is sensible and even necessary. However, proposed measures often come with intrusive requirements and enforcement mechanisms.”

Yet the report is unsparing about the systemic weaknesses that plague donor-funded NGOs and open them to attack.

One is that the NGOs often don’t have a strong local constituency, which allows them, with some justification, to be responsive not to the country’s citizens but to foreigners.

“Demands for accountability also play on the fact that in many contexts, CSOs do not draw on a large membership base. While many Western CSOs have developed extensive member networks over many decades, for issues ranging from civil rights to bird-watching, membership numbers in other countries remain comparatively low,” the report says. In cases where foreign donors back an organization, “the direction of the funding stream reverses accountability of the CSO and its leadership toward donors and away from the membership base.”

Another is that local NGO officials often get generous salaries, which is necessary to compete for highly qualified staff but opens the groups to criticism that they represent only a privileged elite.

Combating those perceptions “requires sophisticated counter-messaging,” Gutbrod writes.

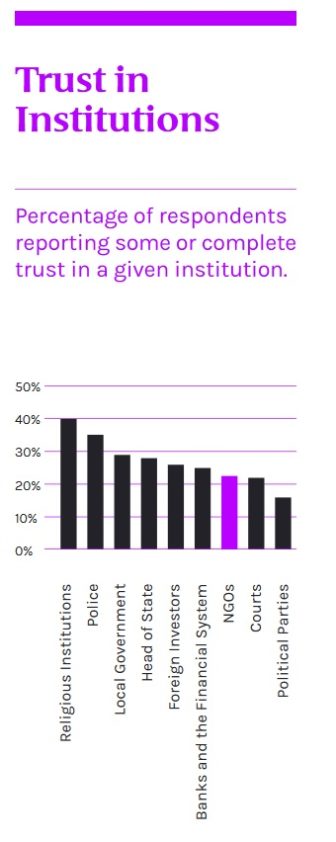

But in many cases civil society groups are unaware of their lack of public support. The report cites research in Armenia, which showed that “CSOs greatly overestimate the trust that they enjoy.” According to the 2013 study, NGO leaders believed that 48 percent of the population “fully or somewhat trusts” NGOs. But the real number was 18 percent. “It is at least possible that this pattern holds in other countries as well,” the report argues.

But in many cases civil society groups are unaware of their lack of public support. The report cites research in Armenia, which showed that “CSOs greatly overestimate the trust that they enjoy.” According to the 2013 study, NGO leaders believed that 48 percent of the population “fully or somewhat trusts” NGOs. But the real number was 18 percent. “It is at least possible that this pattern holds in other countries as well,” the report argues.

And a lack of transparency does in fact plague many organizations — even those that advocate for transparency from governments. At the 2015 International Open Data Conference in Ottawa, “only 12 out of 34 organizations provided comprehensive information on their funding. Many open-data advocates were opaque.”

So what to do? The report advocates a variety of PR and legal measures that groups could take to prepare for attacks from authoritarian governments. But they should not give up pushing for transparency, even as the same argument can be used against them: “the overall pro-transparency strategy remains sound, though continuously adapting the tactics to context will help achieve greater impact,” the report concludes. “The language that grantees use with donors likely is not the language that always appeals to local constituencies.”

This post first appeared on Eurasianet.org and is cross-posted with permission.

Joshua Kucera is a freelance journalist based in Istanbul. He is Turkey/Caucasus editor at EurasiaNet and his articles also have appeared in Slate, The New York Times, The Wilson Quarterly, The Atlantic, Al Jazeera America, Roads & Kingdoms, and Jane’s Defence Weekly.

Joshua Kucera is a freelance journalist based in Istanbul. He is Turkey/Caucasus editor at EurasiaNet and his articles also have appeared in Slate, The New York Times, The Wilson Quarterly, The Atlantic, Al Jazeera America, Roads & Kingdoms, and Jane’s Defence Weekly.