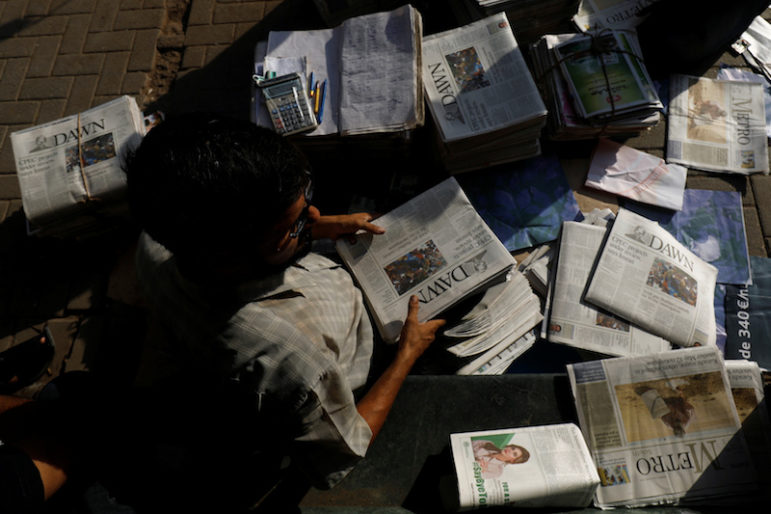

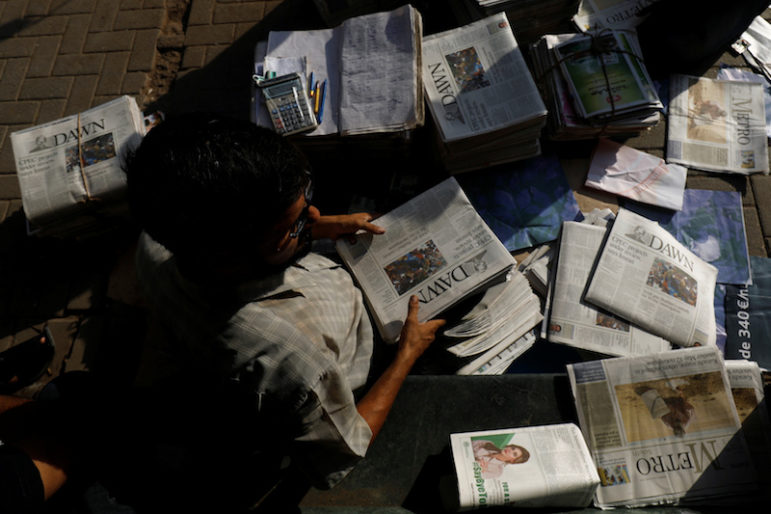

A hawker sorts out newspapers as he sells them along a street in Karachi, Pakistan. Photo: Reuters/Akhtar Soomro.

Dawn, Pakistan’s Paper of Record, Under Pressure as Military Tightens Grip

Baqir Sajjad was unlocking his car after meeting a British diplomat at a renowned café in an Islamabad market when he was approached by two men in civilian clothes.

“Why did you meet him?” he was asked. Sajjad – who is a foreign affairs and national security correspondent for Pakistan’s leading English newspaper Dawn – was exasperated. He showed them his credentials and explained it was part of his routine to meet diplomats from all over the world.

The men, whom Sajjad believed were “low-level intelligence operatives,” demanded he come with them for questioning. Upon his refusal and demand that they present a formal arrest warrant, the men forcefully pulled out the keys from Sajjad’s car and warned him that there would be consequences for not complying.

“I was very scared; I didn’t know where they would take me,” a shaken Sajjad recently told GIJN. “I have never faced such an incident in 12 years of my reporting on a beat as sensitive as national security.”

While he was not detained, what happened with Sajjad is one of the many “firsts” in Pakistan’s journalism landscape, which has come under immense pressure “as the country’s powerful military quietly, but effectively, restricts reporting by barring access, encouraging self-censorship through direct and indirect acts of intimidation,” according to an investigation by the Committee to Protect Journalists.

It is just one of the pressures bearing down on Pakistan, which is the world’s sixth most populous country and is nuclear armed. It came close to another war with India earlier this year after Pakistan retaliated for Indian airstrikes, which were a response to a terrorist attack in the Indian-administered Kashmir that they claimed a Pakistan-based jihadist group was behind. The country is also in the throes of an IMF bailout as the new government under former cricketer-turned-politician Imran Khan struggles with the deteriorating economy.

Dawn, which has retained its reputation as one of the country’s independent media outlets, has become the face of these crises.

In one of the latest tactics to pressure Dawn, the government revoked its advertising in the newspaper, as well as its sister TV channel, DawnNews. Reporters Without Borders condemned the move as a “crude intimidatory tactic” and demanded an end to “one of the most insidious forms of coercion” that jeopardized the paper’s independence.

The latest unofficial ban on providing advertisements to Dawn came after the newspaper published Khan’s remarks during his visit to Tehran in which he publicly admitted that terrorists had used Pakistan soil to undertake attacks in Iran – a claim long denied by the country’s security establishment.

In response, Amnesty International’s Rabia Mehmood decried the “brutal crackdown on freedom of expression in Pakistan,” which she said escalated in 2018, in the lead-up to the general elections. “In addition to censorship, journalists and media staffers have faced arrests, false police cases, allegations of sedition, surveillance, harassment and warnings of dismissals over social media posts, and job cuts in the last year and a half.”

While many speculated whether these tactics would affect Dawn’s editorial independence, Hasan Zaidi, who edits the newspaper’s weekly EOS Magazine, said he didn’t feel any significant changes. “Dawn, unlike many other media outlets, remains editorially independent of management and there has been no pressure or interference from the management so far,” he said. However, due to the financial situation, the newspaper, including Zaidi’s magazine, had to cut down its pages.

“Obviously, there is sometimes self-censorship now where reporting on issues is likely to provoke a backlash from state organizations and we often weigh what the repercussions might be,” he said. Reporting on the military has always been difficult in Pakistan, but more recently stories about the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (Pashtun Protection Movement) have also become a no-go topic for most journalists, Zaidi said, although he pointed out that Dawn has been covering it nevertheless.

But the ad ban for Dawn is not the first time the government has tried to coerce the newspaper into silence. Last year, the paper’s circulation was disrupted in several cities.

“Multiple reports are also coming in of officials posted in many cities and towns in Punjab, arbitrarily summoning newspaper agents, hawkers, and salesmen, and warning them not to distribute copies of Dawn, threatening them with consequences if disobeyed,” the newspaper said in a statement at the time.

Previously, Dawn’s assistant editor and a regular columnist, Cyril Almeida, was barred from leaving the country after he reported an exclusive story detailing the conversations from a national security meeting during which the civilian leadership had warned the military of international repercussions if the latter did not act against the militants. In 2018, Almeida faced treason charges when he conducted an interview with former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, where he implicitly criticized the military’s policies towards militant groups.

While Almeida was named the International Press Institute’s 2019 World Press Freedom Hero for “his tenacious coverage of the Pakistani state’s patronage of militant groups,” his weekly Sunday column remains discontinued.

One Dawn staff writer who preferred not to be named due to security concerns said there has been a “massive shift” in the newspaper’s editorial policies over the last few years.

“The government ads were also revoked after we reported the attack on a reputed hotel in Gwadar on our front page,” the journalist told me, referring to the developing port city in the turbulent Balochistan province that represents the progress on the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, which is part of China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative.

Both Zaidi and the staff writer confirmed that there had been major pay cuts in employee salaries, ranging from 20% to 40%. Senior staff have warned that if pressure continues, Dawn might shut down in two years.

The new government under Imran Khan refused to pay advertising bills from the previous administration, triggering a crisis in the news media that left several prominent journalists unemployed and caused news channels to shut down. According to Zaidi, the government owes around 8 billion Pakistani rupees (more than $52 million) to the news outlets, including Dawn.

But Dawn’s former editor Abbas Nasir said that the cancellation of ads after the publication of critical stories is not new.

“The government revoked ads for Dawn in 2006 after I pulled all the stops to report on Balochistan following the killing of Nawab Akbar Bugti when the military raided his hideout,” Nasir said, referring to the death of a tribal leader that triggered a separatist insurgency in the southwestern province.

Zaidi believes that, apart from the deliberate targeting of critical media outlets, several other elements come into play with regards to the depleting revenues for Dawn. “The advertisers, like elsewhere in the world, are moving away from print and are investing in broadcast and digital media,” he said, adding that the recession is also affecting revenues.

Nasir believes the problem is far more complex. “If it were a market-based challenge, Dawn could respond with a market-based solution, but this is far more sinister,” he said.

Zaffar Abbas, Dawn’s long-time editor, was a bit more pointed: “They are no longer trying to kill journalists,” he recently told GIJN. “They are trying to kill journalism.”

Umer Ali is a journalist reporting on human rights, conflict and censorship. For his reporting on blasphemy and religious minorities in Pakistan, he won two prestigious journalism awards in 2016 including the Kurt Schork Memorial from Thomson Reuters and the print journalism award by the London-based Frontline Club.

Umer Ali is a journalist reporting on human rights, conflict and censorship. For his reporting on blasphemy and religious minorities in Pakistan, he won two prestigious journalism awards in 2016 including the Kurt Schork Memorial from Thomson Reuters and the print journalism award by the London-based Frontline Club.