Image: Nyuk for GIJN

Advice from a Pioneer of Investigative Journalism in the Chinese-Speaking World

Read this article in

In any discussion of investigative reporting in Taiwan, one name inevitably arises: Sherry Lee Hsueh-li. As the current chief operating officer and deputy CEO of The Reporter — Taiwan’s first nonprofit media outlet established by a public foundation — she is not only an award-winning investigative journalist but also a pioneer forging a new path for reader-sponsored investigative journalism in the Chinese-speaking world.

With a career spanning over 25 years, Lee began her journey as a reporter at Taiwan’s renowned CommonWealth Magazine. She steadily rose through the ranks to become deputy editor-in-chief and the head producer of its video division. From 2010 to 2012, she also served as the magazine’s Beijing correspondent.

By 2015, the global shift to social media had reshaped Taiwan’s news industry, with many outlets prioritizing clicks and trending topics. This left journalists under immense pressure, with dwindling resources for in-depth work. Concerned about this trajectory, Lee and a group of colleagues began searching for a sustainable model for journalism — one free from the demands of advertising and traffic. They drew inspiration from a growing wave of nonprofit newsrooms worldwide, including ProPublica in the US, Correctiv in Germany, Newstapa in South Korea, and Waseda Chronicle in Japan. United by the question: “Can we forge a different path?” they officially launched The Reporter on September 1, 2015.

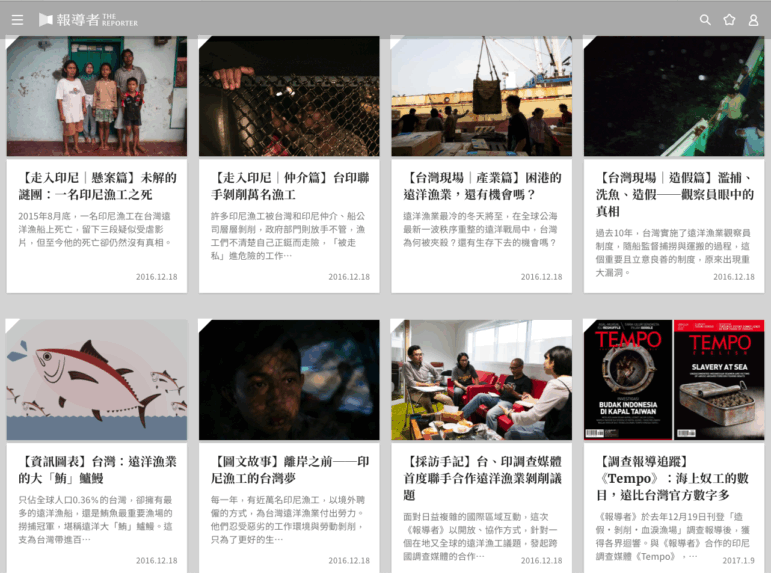

Since The Reporter’s founding, Lee and her team have tackled numerous difficult social and public issues, producing a series of high-impact investigations. Starting in 2016, the three-part series Slaves of the Far-Sea Fishing was The Reporter’s first cross-border investigation and the breakthrough project that established its credibility and reputation. The team conducted a long-term investigation into the labor exploitation of foreign fishermen in Taiwan’s distant-water fishing industry. Through exhaustive interviews, it not only exposed the industry’s hidden operations but also successfully pushed for policy changes. Taiwan passed the Three Acts on Far-Sea Fishing in early 2017 and the minimum monthly wage for migrant fishermen was raised from US$300 in 2016 to US$550 in 2022.

Lee excels at starting with individual problems and social issues, piercing through the surface to dig into the structural roots of the problem. For The Reporter’s 2018 series Youth in the Ruins, she and her team interviewed over 100 teenagers from high-risk families, revealing their struggles to work and live amidst adversity. The series questioned how Taiwan’s social welfare, education, and labor systems had systematically failed this group of invisible and marginalized people. The report resonated deeply with the public, sparking profound reflection on the issue of family dysfunction.

It’s the social impact of these investigations that has earned the trust and support of readers. In its first month, The Reporter had only four regular monthly donors. Today, a decade later, that number has grown to almost 8,000. By steadfastly adhering to its principles of accepting no advertisements and having no paywall, The Reporter — which became a GIJN member in 2017 — has carved out a new path in the Chinese-speaking world, one that relies on reader support to focus on major public interest reporting.

Lee will be a keynote speaker at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, this year. Ahead of the conference, GIJN spoke with Sherry about the state of investigative reporting in Taiwan, the principles and challenges that define her work, and her strategies for coping with professional burnout.

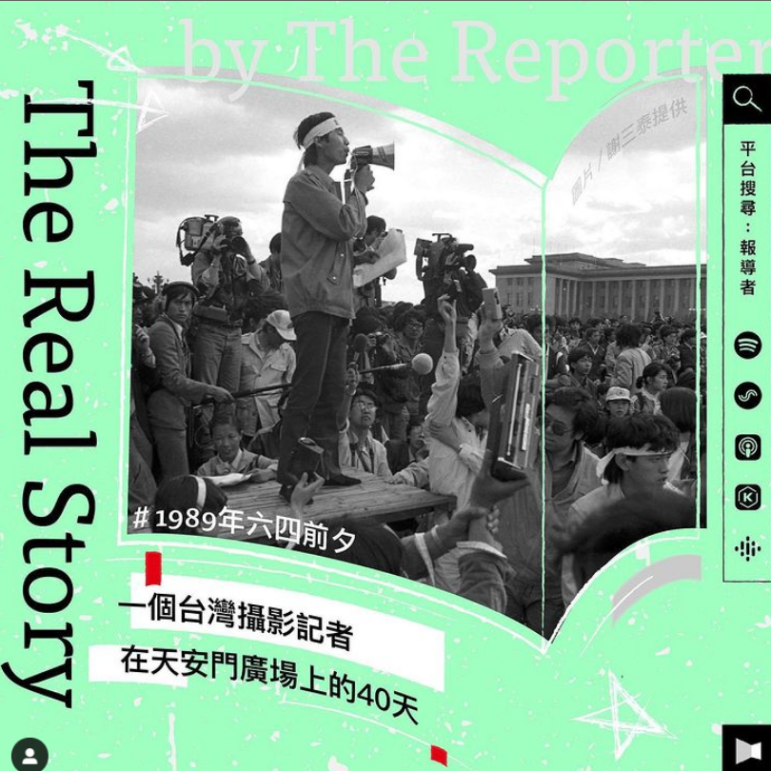

The Reporter’s collaborative multi-part series with the Indonesian site Tempo dug into the labor exploitation of foreigners in Taiwan’s far-sea fishing industry — and prompted changes in the country’s law for fairer pay. Image: Screenshot, The Reporter

GIJN: Of all the investigations you’ve worked on, which has been your favorite and why?

Sherry Lee: My favorite would have to be Slaves of the Far-Sea Fishing, particularly our collaboration with the Indonesian media outlet, Tempo. We had to overcome numerous barriers — language, culture, and systemic differences — to conduct a deep, collaborative investigation into a case that spanned both our countries and involved multiple government agencies. For our team at The Reporter, it was our first true international collaboration. Everyone, from the frontline reporters to the editors, was learning and adapting throughout the process. Tempo’s long-term focus on human trafficking was invaluable; it sharpened our analysis of the evidence and helped us pinpoint the most effective angles for the story.

There is a grounded satisfaction that comes from focusing on a single topic for so long and witnessing gradual improvements in that sector. It gives you a profound belief in the value of what we do as investigative journalists. Furthermore, each part of the trilogy also pushed our boundaries in storytelling. Everyone involved — our writers, photographers, data journalists, designers, and engineers — collaborated with incredible dedication. Beyond the solid investigation, the multimedia presentation on our website is like a work of art. Even today, it remains a powerful and resonant piece of work.

GIJN: What are the biggest challenges in terms of investigative reporting in your country?

SL: The biggest challenge is the state of high pressure and chronic fatigue that journalists constantly face. Most media outlets are trapped in a race for clicks, chasing trending topics. When they face pressure from advertisers or for sponsored content, they are often unable to properly fulfill their role as watchdogs and investigators. Over time, this erodes the industry’s motivation and capacity for in-depth reporting.

Even for the few commercial and nonprofit media outlets that strive to maintain their independence, investigative reporting requires experience, sources, and time — all of which rely on a team’s cumulative knowledge and the ability to pass it down. However, journalist turnover is currently very high. Many are choosing to leave the profession after facing online attacks and harassment. If young journalists can’t build a long-term career in this field, we will face an even more severe talent drain. I believe this is the deepest and most intractable challenge facing investigative journalism in Taiwan today.

GIJN: What’s been the greatest challenge that you’ve faced personally in your time as an investigative journalist?

SL: The greatest challenge is always finding the “smoking gun” — that single piece of irrefutable evidence that lays the truth bare. It’s the only way for a story to have real impact, to cut to the heart of an issue and effectively challenge power structures.

Investigative journalists aren’t the police, prosecutors, or judges. Our goal isn’t to convict people, but to bring the truth to light. This often means we have to challenge powerful interests and expose uncomfortable and unpopular “inconvenient truths.” Yet, unlike the police or prosecutors, we don’t have any official powers of investigation.

This challenge is amplified in our current era of declining media trust, where our work is often seen as a tool for pushing an agenda. Those in power have far more resources to manipulate the legal system and public opinion, which puts journalists in an incredibly vulnerable position. We often endure an agonizing wait for that one piece of decisive evidence — which may never materialize. And when a lead does surface, we must verify it with speed and rigor, all while consciously avoiding the trap of confirmation bias.

For me, the greatest challenge is to keep going on the days when you find nothing, to persevere and never give up until the very last moment.

GIJN: What is your best tip for interviewing?

SL: Everyone is discussing whether AI will replace various jobs. In journalism, tasks like transcribing audio, collecting data, and reading background materials are indeed being increasingly outsourced to AI. I’ve seen many journalists even use AI to draft interview outlines, transcribe all their audio, and have AI read and summarize information for them. While these tools undoubtedly save time, it makes me wonder: If we hand everything over to AI, does the memory and thought process that should be internalized by the journalist become shallow and superficial?

I believe that when we personally read the materials and learn the jargon and context of a specific field, the interviewee can sense the sincerity and dedication behind that painstaking effort. This is something a machine cannot imitate — the inquisitive look in your eyes, the detailed follow-up questions that can elicit a much deeper response.

Listening to the audio yourself is just as important. You hear the shifts in their tone, a sigh, a moment of hesitation. Those emotional cues and nuances are difficult to capture in an AI-generated summary. An interview is not just an exchange of information; it’s the process of building trust between two people.

AI can assist, but it cannot replace. I believe the best interviews come from a knowledge base you’ve built yourself, a sharp ability to ask the right questions, and the human spark that ignites between you and your interviewees.

GIJN: What is a favorite reporting tool, database, or app that you use in your investigations?

SL: Our team’s most common practice is to write our own code to scrape and analyze data. For general-purpose data collection tools, we would recommend ChatGPT and Gemini. They can be very helpful for initial data organization. For maps and geospatial information, we use the open-source QGIS as well as ArcGIS. ArcGIS is particularly useful because it offers a free plan for NGOs, which is a very practical option for media teams with limited budgets.

GIJN: What’s the best advice you’ve gotten in your career and what words of advice would you give an aspiring investigative journalist?

SL: I’ve always loved a passage from “Letters to a Young Journalist.” [A 2006 book written by Columbia Professor Samuel G. Freedman.] Whenever I feel frustrated or doubtful, these words give me strength and warmth:

“I’m not trying to scare you off. I hope you find the challenges inspiring. When I was your age, the cachet of journalism attracted plenty of poseurs. One thing you can say about the present unpopularity of journalism is that it drives out all the uncommitted. If you’re a true believer, if this is meant to be your life’s work, then nothing and nobody can change your mind. Even in a bleak period for journalism, you can find signs of vitality.”

These words always bring me back to my core motivation: I chose this path because I believe in its intrinsic value, not because it is popular or prestigious.

To those of you who want to become investigative journalists, I would say: Protect your curiosity and keep an open mind. Don’t be afraid to tackle difficult issues, and don’t let gender or any other label limit who you are or what you can achieve. Sincerity, resilience, and conviction will be your most essential assets on the path ahead.

GIJN: Who is a journalist you admire, and why?

SL: It’s impossible to name just one, as there are so many journalists who command admiration. I was deeply moved reading the biography of Marie Colvin; her spirit and unwavering commitment to bearing witness from the front lines of conflict were extraordinary.

I also greatly admire Associated Press investigative reporter Martha Mendoza. I was incredibly inspired by her presentation at a GIJN conference. She is focused, determined, constantly honing her craft, and remarkably willing to share her investigative methods with her peers — a rare and generous mentor in the field.

And Diane Ying, the founder of Taiwan’s CommonWealth Magazine. She established the publication in 1981, while Taiwan was still under martial law, creating the island’s first magazine to pair a global perspective with a deep commitment to local issues. She is a lifelong learner, and her passion for the news and her dedication to mentoring the next generation are profoundly admirable.

Ah, I just realized that the three journalists who came to mind are all female journalists.

GIJN: What is the greatest mistake you’ve made and what lessons did you learn?

SL: In one investigation, our team took what we thought were sufficient measures to anonymize a confidential source. Despite our efforts, after the story was published, the source was identified by several people, which caused him a great deal of trouble.

That experience was a profound lesson: even when a source agrees to the terms of their protection, the ultimate responsibility lies with us. You can never be too careful when the stakes are high. As the project leader, I learned that for any high-risk story, I must personally lead a more rigorous and granular risk assessment with our writers and photojournalists. This is especially critical in the final editing stages, where we must be relentlessly vigilant, checking every detail multiple times before publication.

GIJN: How do you avoid burnout in your line of work?

SL: Beyond the standard advice of maintaining a routine with exercise, reading, and movies, I’ve also recently made a conscious effort to reduce my time on social media to limit my exposure to toxic discourse.

What truly sustains me, however, is the feedback from our community. Every month, our team shares messages from readers and supporters. Hearing that a story or a podcast moved someone, changed their perspective, or even spurred them to action is a powerful reminder of why we do this work. That sense of connection and impact is the fuel that keeps me going.

GIJN: What about investigative journalism do you find frustrating, or do you hope will change in the future?

SL: The relentless pace can be the most frustrating aspect of this work. Investigative reporting is all-consuming, yet after pouring months of time and energy into a major project, there is often no time to recover before the next one begins. I hope that media organizations will invest more in robust mental and physical health support systems to help journalists build and maintain resilience against the long-term pressures of this job.

I also hope for a deeper public understanding of the sheer difficulty and value of investigative journalism. I hope this understanding translates into more practical support — whether that means reading our work on our own websites, becoming a financial supporter, or simply sharing our stories with friends and encouraging them to engage with quality media. Ultimately, that public support is the vital force that ensures investigative journalism continues to exist.

Joey Qi is the Chinese editor of GIJN and a journalist based in Vancouver. He has worked for multiple news outlets in Hong Kong, spanning various roles from reporter to editor to management roles. His work focuses on China politics, social issues, and labor rights.

Illustrator: Nyuk was born in 2000 in South Korea. He is currently studying at the Department of Applied Art Education at Hanyang University in Seoul, South Korea, where he also works as an illustrator. Since an exhibition at Hidden Place in 2021, he has participated in various illustration exhibitions. He is mainly interested in hand drawing, which represents the value of his art world.