Image: GIJN

Notes from a Small Island: Bernadette Carreon on Covering Palau, the Pacific, and the World

When, as a young journalist, Bernadette H. Carreon took a reporting job at a newspaper in the small Pacific island nation of Palau; she didn’t know it would become her home — and reporting beat — for the next 20 years.

Born and raised in Manila, Carreon studied journalism at the University of Santo Tomas, and worked in the capital before making the move from the Philippines — with a population of 118 million — to Palau, with a population of 21,000 — to work for the now-defunct Palau Horizon.

“I wanted to do something different, and I wanted to travel,” Carreon told GIJN. “Palau was the first place that had a vacancy for a reporter. I was young. I wanted to try it for a year, and the rest is history.”

For more than two decades, Carreon was based on a small island but covered a vast beat — the Pacific — for local outlets and international newspapers and agencies, including the Guardian, Agence France-Presse, and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, covering topics as diverse as Palau’s cryptocurrency plans and the global seafood industry.

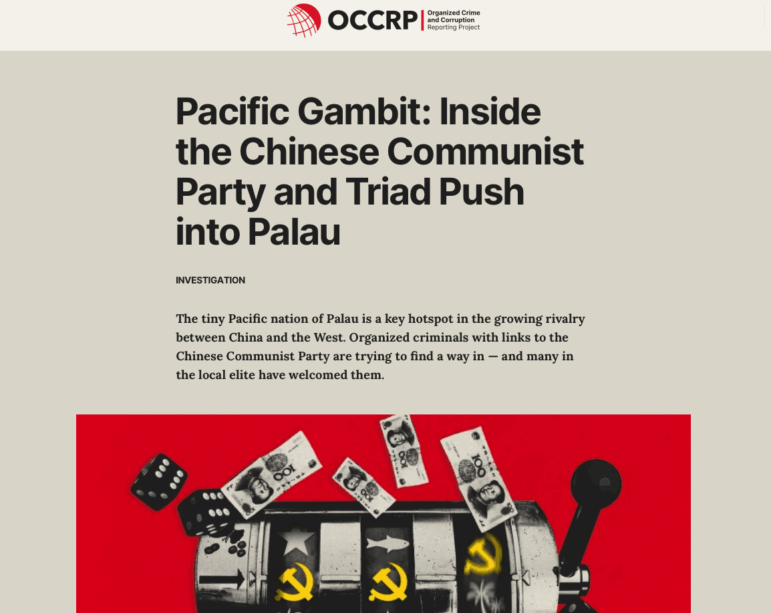

As the OCCRP’s Pacific investigative reporter, she worked on the 2022 story Pacific Gambit: Inside the Chinese Communist Party and Triad Push into Palau, which exposed how her adopted home had become a front in the rivalry between China and the West. The OCCRP reported that “string of questionable ventures” in Palau, such as illegal online gambling operations connected to organized crime figures, were not a matter of “isolated criminal outfits,” but Beijing’s latest step in an attempted push into the Palau — a strategic Western ally in the Pacific and one of only 14 nations that diplomatically recognize Taiwan.

Palau-based investigative reporter Bernadette Carreon was a collaborator on OCCRP’s exposé on organized crime and the Chinese Communist Party’s activity in the Pacific region. Image: Screenshot, OCCRP

She is also the project manager for the Pacific Freedom Forum, a press freedom watchdog raising funds for Pacific-based journalists to help them fight legal action and intensifying attacks against their work.

GIJN spoke with Carreon, who is now based in the United Kingdom, about her favorite investigation, her “old-school” journalism heroes, and how to navigate reporting where everyone knows your name.

GIJN: Of all the investigations you’ve worked on, which has been your favorite and why?

Bernadette Carreon: The Pacific region and Pacific journalists are still new to investigative journalism. But one of my favorites is Pacific Gambit: Inside the Chinese Communist Party and Triad Push into Palau. The story has legs to it. Although the investigation was published in 2022, it has been referenced a lot by international publications on organized crime. It also made Palau known for political stories. International reporters who come to Palau now always include stories on geopolitics and the Chinese Communist Party (CPP)’s alleged influence in the region. It opened up the subject of alleged CCP influence in the Pacific.

GIJN: What are the biggest challenges in terms of investigative reporting in your country/region?

BC: I’ve spent my time in the Pacific, in Palau, specifically, for over 20 years. Palau is small, really small. Small can be good, and small can be bad. It has its benefits and its hindrances. It can be hard to do investigative reporting because everyone knows you, and everyone knows where you live. And when I was starting, technology and the internet weren’t as good as they are today. Also, because everyone knows me there, it can be hard to do investigative journalism because everyone knows who reported it.

And also, when I arrived in Palau, I was an overseas worker, a foreign worker. Palau also didn’t really respect journalists at the time, and it was hard, especially because I was not from there. It was hard for me to report because there was a lack of respect, and I was a foreigner. My status in Palau at that time was based on my immigration papers. So I could be sent home.

GIJN: What’s been the greatest hurdle/challenge that you’ve faced in your time as an investigative journalist?

BC: Of course, censorship. In Palau, they have this respect for the elders. They have this respect for politicians, for people in authority. It’s the culture that you don’t shame your elders, and you don’t shame someone who’s in authority. To me, the biggest challenge is self-censorship. Because I’m part of the community. Sometimes I think, who would I hurt? Would I shame people around me? I see them in personal events, like school events with my child, or parties, or the supermarket, because Palau is so small. And people don’t tend to talk. It can be difficult to find sources and information. Getting documents is also hard, they won’t easily give them to you because they’re a higher authority from whom you have to ask permission.

Funding is a challenge. Investigative journalism takes time and resources. And usually it’s a one-woman show or one-man show, or a small newsroom. So you’re the editor, you’re the photographer, you’re the reporter, you’re the driver. That’s just so taxing emotionally and financially.

GIJN: What is your best tip for interviewing?

BC: Those who have worked with me would probably say that I have a good communication style, that I am direct and firm, but respectful. You have to listen to what people are saying. Because I’m from the Philippines, we have a saying — I’m going to try to translate it — ‘if you talk to everyone, no information is a waste.’ Have a conversation with people you are interviewing; don’t just ask questions that feel like interrogation.

I also do like to research the people I interview: What kind of questions will make them angry, or are they someone who will be evasive? So I have to think of a way to ask that question, so I research the person I’m interviewing. I try to use the right words, the right tone to interview, a tone that’s not aggressive, a tone that’s very warm, but at the same time, direct.

GIJN: What is a favorite reporting tool, database, or app that you use in your investigations?

BC: I’m old school; the way I do reporting is building sources. I like to talk to people. So, messaging apps. In the Pacific, people still like to use Facebook Messenger, so I talk a lot to my sources through Facebook, because if you see them or meet them in a coffee shop, because it’s a small country people will say, ‘Why is she talking to the reporter?’

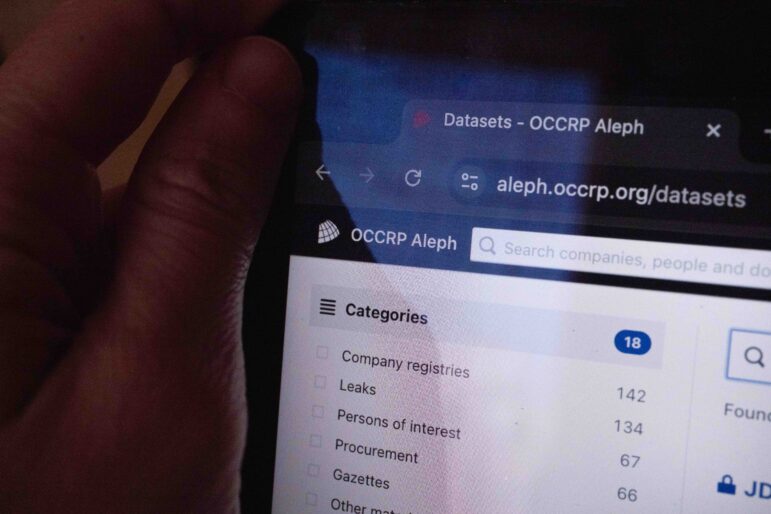

And when I was working with the OCCRP, I relied a lot on their Aleph tool — a great database on public information with a large dataset. I did use that, especially in the Pacific Gambit story.

GIJN: What’s the best advice you’ve gotten thus far in your career, and what words of advice would you give an aspiring investigative journalist?

BC: I’m not sure it was advice to me, but I heard it at the last Global Investigative Journalism Conference (GIJC2023) in Sweden. One of the panelists said that investigative journalism is really hard, so it’s a team sport. You can’t do it alone — it involves collaboration with other journalists, editors, and researchers.

From my editors, the best advice I got is not to take everything personally. To aspiring investigative journalists, I would say be patient. Be patient, because if you are impatient, you kill a story.

GIJN: Who is a journalist you admire, and why?

BC: Because I’m old school, probably the biggest ones are Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, who broke the Watergate scandal, because we studied that in the journalism school in the Philippines. And of course, I’m from the Philippines, so I admire Maria Ressa. She opened up the Philippines to investigative journalism. I like Christiane Amanpour, who gets interviews that nobody else does. And from The New York Times, I admire Megan Twohey — she does a lot of stories that impact women and also exposes systemic failures.

GIJN: What is the greatest mistake you’ve made and what lessons did you learn?

BC: I have made a lot of mistakes. The first mistake I made was when I was working in Manila as a young reporter. There are a lot of journalists in Manila, and it’s very competitive. I always went with a pack of young reporters, and we would kind of do stories together. There was a story where we thought we had an exclusive — but it turned out the story was not true, and it was published… I don’t know how I kept my job, probably because I was young at that time, some of the more senior reporters protected me and defended me. Don’t believe what one source says, even if they’re a person in authority — it doesn’t mean that they are going to tell you the truth. Always fact-check.

I made a lot of mistakes. There were stories where I was scared to ask questions, or I didn’t want to do it because it was scary. Then one of my editors said, ‘Well, if you don’t want to do the story, then don’t come back to the office.’ Those are the mistakes I do — to show fear.

GIJN: How do you avoid burnout in your line of work?

BC: Take a break and do something other than being a reporter, like hobbies. It’s nice to have a group of other journalists who understand you, so you can talk to them about what you’re feeling, because it can take an emotional toll on you. As Buddhist philosophy says, empty yourself. If you’re going to another investigation, just get rid of the stuff that you’ve already done and move forward.

GIJN: What about investigative journalism do you find frustrating, or do you hope will change in the future?

BC: Coming from a small region and having moved to the UK, I find it hard to get into investigative journalism because my experience is from one region. That’s the thing about being in a small region — you don’t become an expert on only one issue. Because you have to cover everything from sports to geopolitics, from politics to the environment.

Also, that there won’t necessarily be an immediate result [when pursuing a story], because there are a lot of dead ends in a story. And that your story and pitch depend on your editor or the publication you’re writing for — they can make decisions for you that this story is not worth pursuing, even when you know in your gut that it is. And of course, lack of funding, especially in this environment at the moment.

Alexa van Sickle is a journalist and editor with experience across digital and print journalism, publishing, and international think tanks and nonprofits. Before joining GIJN, she was senior editor and podcast producer for the award-winning foreign correspondence and travel magazine, Roads & Kingdoms.

Alexa van Sickle is a journalist and editor with experience across digital and print journalism, publishing, and international think tanks and nonprofits. Before joining GIJN, she was senior editor and podcast producer for the award-winning foreign correspondence and travel magazine, Roads & Kingdoms.