A Right, Not a Privilege: Tips on Covering Education

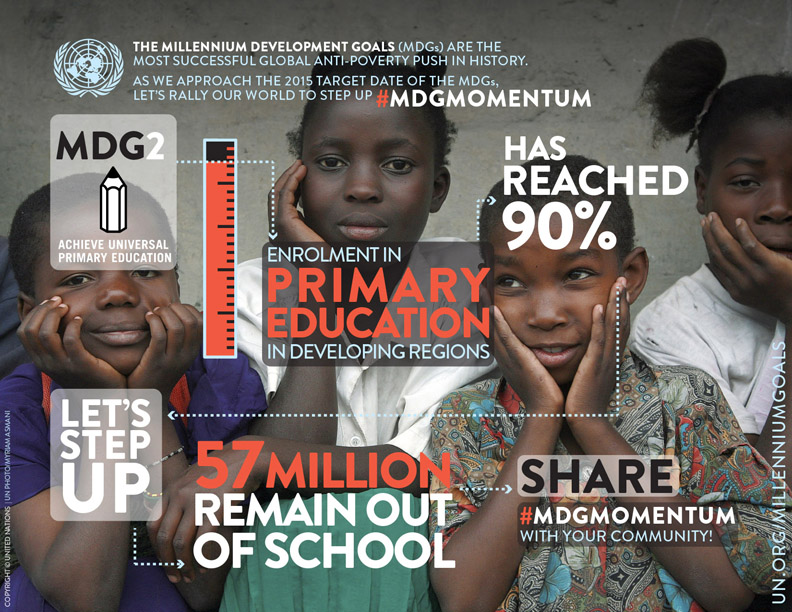

Part 7 of a series GIJN is excerpting from the Reporter’s Guide to the Millennium Development Goals: Covering Development Commitments for 2015 and Beyond, published by the International Press Institute.

Part 7 of a series GIJN is excerpting from the Reporter’s Guide to the Millennium Development Goals: Covering Development Commitments for 2015 and Beyond, published by the International Press Institute.

Education is the path to development. It creates choices and opportunities for people in terms of access to employment, reduces the twin burdens of poverty and disease, and empowers people. For nations as a whole, education produces a more skilled and competitive workforce that can attract better quality foreign investment, thus opening the doors to economic and social prosperity for society as a whole.

However, people often do not see how these global goals can be translated to local realities. The media plays a key role in forming opinion, helping to ensure that citizens and politicians alike recognise that there is no room for complacency in tackling the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) related to education (hereafter, MDGs on Education). The media also evaluates progress and highlights areas for improvement.

Here are a number of important tips for journalists who cover education issues, based on interviews with education and media experts.

1. Construct positive and negative scenarios that reflect the impact of meeting/not meeting the MDGs on Education

What would happen in your country if all boys and girls completed a full course of primary schooling? How would their lives change? What new opportunities would open up for them? How would society as a whole benefit from this? On the other hand, what would happen if by 2015, the MDGs were not met?

2. Link the MDGs on Education to other targets, such as nutrition, health, and gender equality

The MDGs should not be seen in isolation, but as part of a series of targets that are interrelated. For example, healthier and better nourished children will be able to perform better in school, and better-educated children will have better employment opportunities, a better income and better chances of breaking the poverty cycle as it will be easier for their children to have access to education. Given that studies have shown a clear link between malnutrition and poor performance in school, it is important to consider whether schools offer free food to children from low-income backgrounds; many countries offer primary school children a glass of milk, cereal, or some sort of nutritional supplement.

Also, increasing the number of girls who are able to complete primary school education will produce better-educated mothers who will be positive role models for their children and will help them to succeed in life. Again, articles on education must be linked to other issues such as health, nutrition, and gender equality.

3. Emphasise the link between the MDGs and ensuring basic human rights for all citizens

Education is a right, not a privilege. It is important for readers to understand that access to education is a basic human right, enshrined in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, a multilateral treaty adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 16 December, 1966 and in force since 1976. The right to free education is also guaranteed by most countries’ legal and constitutional frameworks.

“People often blame the poor for their situation and demand that they should pay for primary school education, ignoring the fact that many people do not have the means to pay,” explains Guatemala’s former education minister, Bienvenido Argueta.

It is, thus, important for journalists to emphasise the fact that education is a basic right for all citizens regardless of their social status, which means that if the government is not meeting this basic target, it should be held accountable.

When writing about these issues, it is important to put a human face on the story. An article that just quotes facts and figures can be dry and boring for an average reader while telling a story usually creates empathy. This is very important given that the average newspaper reader is urban and middle class and often takes many things (such as having three meals a day, access to education, and healthcare) for granted.

A good article begins with a personal story, like a camera lens that zooms in on one child in particular, and then provides contextual information on the village where the child and his or her family lives, interviews with parents, teachers, and local authorities as well as statistical information that shows how this story reflects a trend or a common situation.

4. Link the MDGs on Education to issues such as public spending and accountability

How is taxpayers’ money invested in terms of meeting the MDGs on Education? Is it necessary to increase public spending on education in order to meet the targets? Are resources being spent effectively? How can this be improved?

Citizens often complain about poor education standards but are reluctant to pay more taxes in order to increase public spending in this area. Journalists’ coverage of education issues must make all citizens (including the private sector) aware of the importance of meeting their fiscal responsibilities if they want to live in a better-educated and more-developed nation.

5. Targets should be approached qualitatively as well as quantitatively

Progress achieved should not only be measured in terms of how many more children are enrolled in primary school. If the number of children enrolled increases, but the education services are of poor quality and the country’s educational infrastructure has not expanded in order to meet the increasing demand, the gap will remain. “More Guatemalan children are attending school, but the quality of the education they receive is deficient. To what extent are children and young people really learning?” asks Verónica Spross, director of Businessmen for Education (Empresarios por la Educación), a Guatemalan nonprofit whose aim is to promote better standards in education.

Progress achieved should not only be measured in terms of how many more children are enrolled in primary school. If the number of children enrolled increases, but the education services are of poor quality and the country’s educational infrastructure has not expanded in order to meet the increasing demand, the gap will remain. “More Guatemalan children are attending school, but the quality of the education they receive is deficient. To what extent are children and young people really learning?” asks Verónica Spross, director of Businessmen for Education (Empresarios por la Educación), a Guatemalan nonprofit whose aim is to promote better standards in education.

6. Beware of distorted statistics

Official statistics are often presented in a way that seeks to mask reality. Government institutions sometimes present statistics in a way that inflates achievements or underestimates failings.

7. Who teaches your country’s children? What incentives do they receive?

In many countries, teachers are badly trained, and few have reached higher education themselves.

How many teachers have reached higher education? How does the training they receive compare with that of other countries? Does your country’s government offer teachers refresher courses to update their knowledge on specific aspects? Teachers who are badly paid and/or not paid on time are unlikely to perform well. If your country’s teachers barely earn the minimum wage, it says a lot about the government’s priorities in terms of education.

8. If your country has an indigenous population and/or different ethnic and linguistic groups, is bilingual education provided?

Many studies have proven that in countries with large indigenous populations, such as Guatemala and Bolivia, educating children in their own language, in a manner that is culturally appropriate, is an important factor in terms of guaranteeing academic success. The availability and quality of bilingual education can help to explain disparities between urban and rural areas and between indigenous and non-indigenous students.

9. Are school facilities adequate?

Adequate school facilities will have a crucial impact on the quality of education provided.

Overpopulated schools are also forced to run several shifts in the morning and the afternoon, which obviously has an impact on the quality of the learning experience. This is especially common in rural schools.

It is also important to consider the availability of basic materials such as desks, chairs, textbooks, notebooks, pens, and pencils. Many rural schools lack the most basic facilities such as electricity and running water.

10. Coverage should not only focus on shortcomings and failings. It is also important to highlight success stories, and the lessons that can be learned from them.

11. Journalists should consult experts from a wide range of sources and institutions to ensure that their coverage is balanced.

“Reporters usually quote the same experts from the same conservative and right-wing think-tanks, ignoring sources who represent those who are worst affected by the country’s shortcomings in terms of broadening access to education, such as the indigenous population,” says Argueta.

Sources should include experts and academics from a wide range of sources—governmental bodies, public and private universities, think-tanks from across the political spectrum, and NGOs and civil-society organisations that represent the most vulnerable groups in society, such as women and the indigenous population. Often these latter groups are the worst affected by exclusion and the lack of access to education.

Resources

Here are some important indicators that must be taken into account when evaluating progress made in terms of meeting the Millennium Development Goals on Education. All of them must be broken down in terms of gender and urban/rural areas, as global statistics can mask gender disparities or exclusion in certain geographical areas.

- Net enrollment ratio (NER): the number of children at primary/secondary school age that attend primary or secondary school. This will vary from one country to another, as primary school in some countries is for 6- to 12-year-olds and is for 7- to 12-year-olds in other countries.

- Gross enrollment ratio (GER): the total number of pupils attending primary or secondary school (unlike the NER, this includes mature students who are attending primary or secondary schools at a later age).

- School repetition rate by gender and grade: this reflects failings in the standard of education provided or external factors, such as malnutrition, that have a negative impact on a child’s academic performance.

- School desertion rate: how many children leave school before completing primary or secondary school?

- Learning continuity: compare the number of children enrolled in the first year of primary school with the number enrolled in subsequent years. Disparities must be explained — Is there a high repetition rate and is this grossly increasing enrollment in certain years? Do many students leave after completing primary school and fail to go on to secondary school? How many reach higher education?

- The results of standardized, basic numeric and literacy tests performed at a certain age in most countries. Most countries, by law, have to publish this on their websites. These figures are very revealing as shockingly poor results often illustrate the bad quality of education that students are receiving and disparities between public and private schools.

Louisa Reynolds is a British journalist who worked in Guatemala after studying for a master’s degree in Latin American Studies at the University of London. After working for regional magazine Inforpress Centroamericana and the daily elPeriódico, she became a freelance reporter for such media as Siglo 21, Estrategia y Negocios, and foreign publications such as Proceso (Mexico), Noticen (United States) and Noticias Aliadas (Peru). Her interests include poverty reduction and the impact of conditional cash transfer programmes, security and drug trafficking as well as culture and creative journalism.

Excerpted from Reporter’s Guide to the Millennium Development Goals: Covering Development Commitments for 2015 and Beyond. Agreed to in 2000, the UN Millennium Goals comprise an ambitious agenda to improve quality of life around the world, focusing on such issues as poverty, gender equality, and education. This unique manual, available in four languages, offers journalists practical tips on covering these critical areas as we near the 15th anniversary of the goals. Twenty-one journalists across six continents contributed to the report, including several active in GIJN. We are grateful to the publisher, the International Press Institute, for permission to publish the series, and to the European Press Photo Agency and EFE Agency for permission to publish the accompanying photos.