At GIJC25, investigators from The Examination discuss their investigation tying lead pollution to the global auto supply chain. Image: Lisa Marie David for GIJN

Tracing Lead Pollution in Nigeria to the Global Auto Supply Chain

The industrial city of Vernon in Southern California — just south of downtown Los Angeles — had long recorded high lead levels, principally caused by a major battery recycling plant that was eventually decommissioned in 2015.

Soil samples at Vernon’s preschool, taken at the height of the public discovery of the contamination in 2014, contained lead levels of 95 parts per million — a level considered an “elevated” health risk when ingested or inhaled from soil. More than 10 years on, cleanup efforts around Vernon — one of the worst cases of lead pollution in modern American history — are still ongoing.

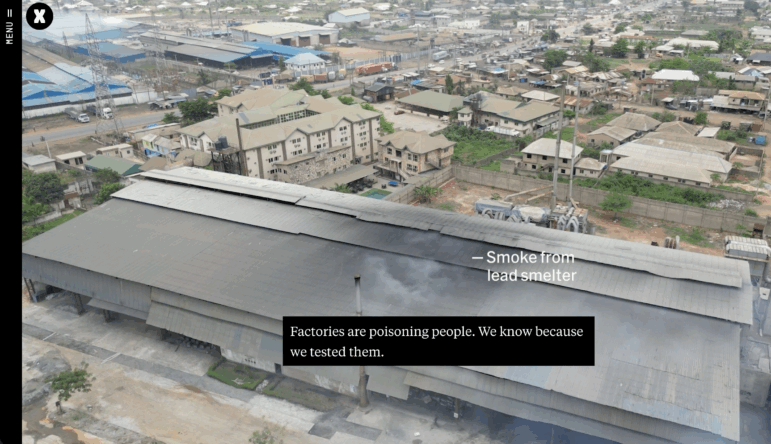

So it’s perhaps not surprising that when a team from The Examination and its partner outlets measured lead pollution in Ogijo, Nigeria — which has more lead recycling factories than anywhere else in Africa — they also found a high level of contamination: 1,900 parts per million, or 20 times the amount recorded in Vernon’s soil. The investigation found that lead recycled in Ojigo from used car batteries is later shipped to supply companies such as Tesla, Ford, and General Motors.

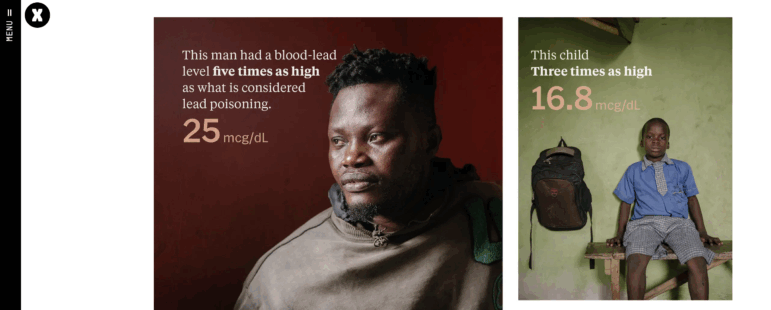

More than half of the children tested in Ogijo registered lead levels in their blood that could cause lifelong brain damage, and all recycling factory workers were found to have been “poisoned” — meaning that their blood lead levels exceeded the five micrograms per deciliter (one-tenth of a liter) threshold at which the World Health Organization (WHO) warns of serious health risks.

During the 14th Global Investigative Journalism Conference (GIJC25), The Examination team shared the innovative reporting methods that underpinned their lead pollution investigation, published in November 2025 in a series of articles, videos, and multimedia visuals. This is how they did it.

Reporting and Collaboration

Tracing lead from international supply lines to Ogijo’s soil and residents involved on-the-ground reporting, data journalism, and scientific research.

Will Fitzgibbon (with microphone), senior reporter and partnerships coordinator for The Examination, speaks during a pre-conference session on investigating global health at GIJC25 in Kuala Lumpur. Image: Lisa Marie David for GIJN

Will Fitzgibbon, the investigation’s main reporter for The Examination, had been following the story for years. “The data that first turned me on to this topic was produced by seven university academics throughout Africa who published a paper about this in 2017,” Fitzgibbon said at GIJC25, and added: “Sure, you should read the latest scientific study by the brilliant journalist in Harvard or Cambridge, but also what the chemistry professor at the University of Nairobi has published.”

In September 2023, Fitzgibbon published a piece reviewing international studies and surveys that warned of prevalent worldwide lead contamination, and in December 2023, a story researched in partnership with The Museba Project, Ghana Business News, and US environmental news site Grist honed in on lead pollution caused by battery recycling in Ghana, Cameroon, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

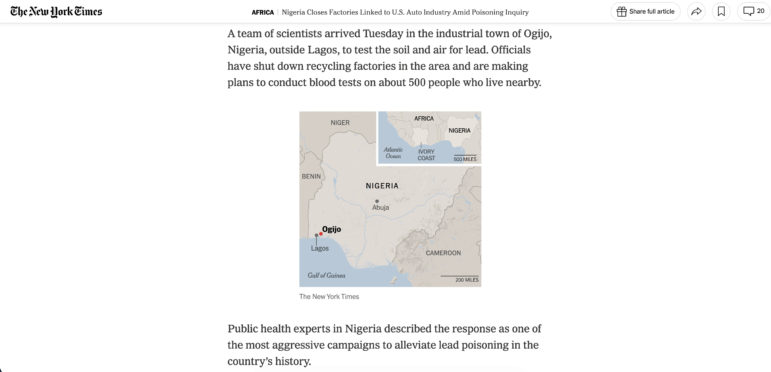

But no story had yet been published that brought all these pieces together, revealing the global supply chain in detail and specifying the damage caused to a community. The team needed to find out what companies in the US were importing batteries, where they were being recycled, and who was affected by the pollution. The Examination focused on the town of Ogijo, near Lagos, Nigeria, and collaborated with The New York Times, as well as local African outlets like Premium Times, Joy FM, Pambazuko, and Truth Reporting Post.

The Examination collaborated with The New York Times, Premium Times, Joy FM, Pambazuko, and Truth Reporting Post to publish several articles, videos, and multimedia in November 2025. Image: Screenshot, The Examination

Revealing the Supply Chain

The team knew that finding — or even creating — the right kind of trade data would be key to the investigation.

“We had a number of pots of data that we knew existed or we knew needed to exist for this story to work,” Fitzgibbon explained. The first of these was the trade data that traced the lead from the polluting recycling facility in Ogijo to a battery manufacturing facility in the US.

Their reporting asserted that US manufacturers have known about these lead pollution problems for years, but have avoided commitments to using lead certified as safely produced. Automakers’ environmental policies — such as those aimed at reducing emissions in accordance with regulations — have not included reducing pollution from lead. Batteries can be recycled cleanly, but that requires millions of dollars in technology. Environmentally responsible battery recyclers in Africa can get pushed out of the business by less scrupulous and cheaper competitors.

Fitzgibbon said the team was lucky to have financial resources from The Examination to help them access several trade databases, through which they could trace exports from places such as Nigeria and Togo, as well as South Korea and the US states of Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

However, there were several gaps in the data, so the team could not rely only on one set. “We discovered we only had a snapshot of trade data if we only looked at one platform, so we needed to look at shipments and containers on different platforms, ” said Romina Colman, The Examination’s data editor. “We were always trying to validate if what we had in one specific database was also present in the second one.”

Image: Screenshot, The Examination

Colman warned journalists that they should be careful with their wording when using trade data: don’t assume you can use expressions like “this company bought this product,” because you can be wrong. If you’re a small team, talk to other people and experts about technical trade terminology. “Always think about how your network can support your work,” she added.

Colman also suggested teams be strict in task distribution. If you’re not a data person, don’t try to analyze datasets; pass them on to the person responsible. “Also, we try not to spend more than five hours straight working on a specific dataset, because after that, you’ll stop seeing errors and make mistakes. Resting is important in investigations. Don’t put 24 hours into one single analysis,” Colman added.

Miriam Wells (left), The Examination’s impact and strategy editor, and Romina Colman, The Examination’s data editor, speaking at GIJC25 in Kuala Lumpur. Image: Lisa Marie David for GIJN

The trade data the team collected allowed them to uncover how a single lead smelter in Ogijo received discarded batteries from abroad, extracted the lead, and then, through Trafigura — one of the world’s largest commodities suppliers — shipped the recycled metal to the port of Baltimore. From there it travelled to East Penn Manufacturing, a battery manufacturer in Lyon Station, Pennsylvania that supplied batteries for carmakers such as Tesla, General Motors, and Ford.

In response to the investigation, East Penn Manufacturing — one of the world’s largest battery producers — said it was unaware of lead pollution from its Nigerian suppliers and ended all imports from them.

Who Was Affected?

Uncovering the supply chain was one part of the investigation; the other was determining who exactly was being poisoned.

“We wanted to say more than ‘Nigeria is exporting lead to the United States and lead is bad.’ We wanted to say: ‘Here is Mrs. Smith, and scientific studies show us that Mrs. Smith has been poisoned because of corporate activity that exports products to the United States,’” said Fitzgibbon.

The Examination contracted a Nigerian nonprofit research group, Sustainable Research and Action for Environmental Development (SRADev), recommended by experts. SRADev had worked with the Nigerian government before, which meant public officials would consider the results credible.

Through events hosted by SRADev, people in the Ogijo community were informed about the project, and 70 people volunteered to have their blood tested. Since old paint and pipes are also common sources of lead poisoning, SRADev distributed nasal filters to detect lead in the air released by the lead recycler’s smelting process. Volunteers who did not live near the factories were also tested to compare the results.

Finally, the University of Ibadan, one of Nigeria’s premier universities, collected and analyzed soil samples near factories. As Olamide Agunbiade, a regional health official quoted by The Examination observed: “If this study was not done, we would just continue with the status quo.”

“Usually, when you report internationally, you go into a community, and you know who you want to talk to and you know something about their story,” said Fitzgibbon. “But in this case, we went into Nigeria for the first time and no one knew if they had blood poisoning or not, because we hadn’t done the blood testing first, so it was an unusual situation, in which the human stories came last, after the scientific work had been done.”

Once people received their results, they had the option of keeping them private or to opt in to being approached by The Examination’s journalists. According to the investigation’s ethical standards, unless the sources volunteered to be contacted by The Examination’s team, SRADev did not reveal their identity to the journalists.

A New York Times article by Will Fitzgibbon and Peter S. Goodman published in December 2025 followed up on the impact of the lead poisoning investigation. Image: Screenshot, The New York Times

Impact on the Community

The team was also thinking about how to generate the most impact, both outside and inside Ogijo. In addition to several articles and short documentary videos, the team deployed community, impact, and service journalism to support the affected communities.

Given that the data revealed had enormous implications for Ogijo’s community, The Examination’s impact producer Funmibi Ogunlesi and impact editor Miriam Wells created a WhatsApp group to keep members of the Ogijo community informed of developments and the materials produced by reporters and the impact team.

“I think it’s really important to think about all the different editorial products that you can create, from the reporting video to the WhatsApp group, which is service journalism,” said Steve Myers, the story’s editor.

“This is an experiment. It’s the first time we’re trying this, so we’ll see how far it can go,” said Ogunlesi. For now, the team uses the WhatsApp group to communicate information about how to reduce exposure to lead, though the impact team has made sure to clearly state they’re not health experts, so they cannot give medical advice.

“Given not everybody has a smartphone in this community, we also worked with a local community radio station, and our impact producer [Funminbi Ogunlesi] is going back to Nigeria, where we’re hoping to do an event to formulate plans, depending on what’s working when we’re there. Our story hasn’t ended. From our perspective, our work has only begun,” Wells said.

So far, The Examination’s investigation has had a significant impact. It revealed unsafe lead smelting practices and explained some of the structural reasons the supply chain makes responsible recycling challenging. Communities have learned the extent of health issues caused by the recycling factories and are receiving support from researchers. Some importers in the US, as well as car manufacturers, have reacted to these disclosures. Last but not least, Nigerian authorities have started cataloging the health and environmental damage caused by the factories, and promised to close some down.

Santiago Villa is an award-winning journalist who has written for Latin American news outlets for more than a decade. He has also worked with humanitarian aid and international development organizations in issues such as preventing forced child recruitment by armed groups. He is currently based in Washington DC and has previously worked as an investigative journalist in Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, South Africa, and China.

Santiago Villa is an award-winning journalist who has written for Latin American news outlets for more than a decade. He has also worked with humanitarian aid and international development organizations in issues such as preventing forced child recruitment by armed groups. He is currently based in Washington DC and has previously worked as an investigative journalist in Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, South Africa, and China.