Illustration: Emil Hasnain for GIJN

Guide to Investigating Food Insecurity

The number of people facing acute, life-threatening hunger nearly tripled in the last decade to 295 million across 53 countries, according to the 2025 Global Report on Food Crises. Conflict was the leading driver, followed by economic shocks and weather extremes.

The number facing long-term chronic hunger, which is not as severe but can cause lasting harm to health and development, is even more staggering. Despite some improvement in recent years, the United Nations estimates 673 million or 8.2% of the global population still suffer from too little to eat. The root causes include poverty, poorly functioning food systems, and economic inequality.

The UN, which raises and distributes some US$30 billion in humanitarian assistance annually, set a goal 10 years ago of eliminating chronic hunger by 2030. By its latest projections, it will fall short by more than 500 million people.

The reasons for such a colossal failure, the scale of human suffering, and the fact that most hunger disasters today are human-made make it imperative to identify who is responsible and hold them accountable. Yet doing so can be immensely challenging.

The obstacles include armed conflict and extreme weather that make roads dangerous if not impassable for those seeking food, those delivering humanitarian aid, and journalists trying to reach the affected region. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, as of September 2025, nearly 200 have died covering the Israel war and humanitarian crisis in Gaza as of this writing. Nine have died in Sudan, where a protracted civil war has led to famine.

Mass movements of people fleeing violence or seeking sustenance also makes it hard to count the victims, while the collapse of social structures reduces reliable information about health and mortality data to document starvation. Government restrictions on media movements pose another barrier to the accurate accounting of hunger.

But journalists have overcome obstacles and detailed the suffering through resolve, resourcefulness, and creativity:

- Famine by Design: How Israel Ignored Warnings Over Hunger and Starved Gaza, a 2025 Haaretz story, assembled a year-and-a-half of public statements by the Israeli government, increasingly dire hunger warnings from international organizations, and social media posts from within Gaza into a timeline, creating a striking piece of accountability journalism on the famine there.

- The Starving World, a 2024 Reuters series, analyzed satellite imagery to document expansion of cemeteries at an isolated location where hundreds of thousands of Sudanese had fled violence, interviewing people living there by cell phone with the help of trusted informants. The effort produced key evidence that global hunger monitors cited in determining that a famine was underway in Zamzam. Reporters then downloaded the minutes of UN food security cluster meetings from ReliefWeb and requested records on food deliveries from the UN’s World Food Programme to document failures in the humanitarian response. Links to the most helpful resources are provided below.

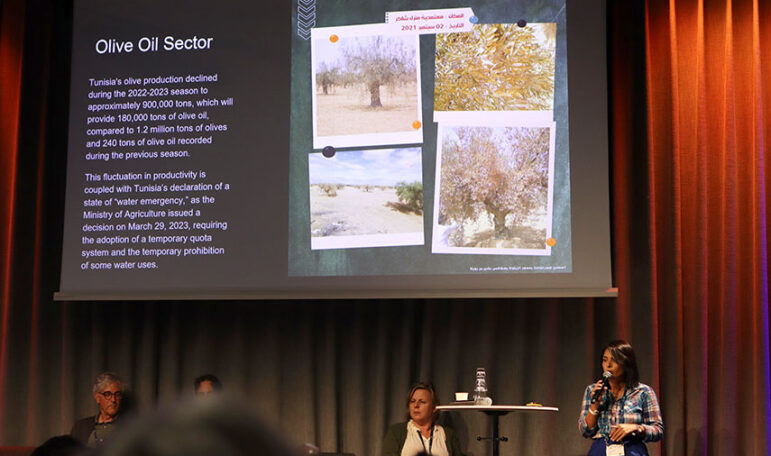

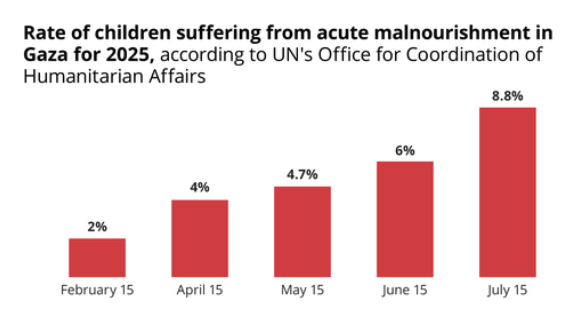

Tracking starvation rates in Gaza over time. Image: Screenshot, Haaretz

Sometimes cause and effect are worlds apart. Additional groundbreaking investigations followed the money — and food — across continents to reveal invisible connections:

- The Black Sea Blockade: Mapping the Impact of War in Ukraine on the World’s Food Supply, a 2022 Guardian investigation, tapped an impressive array of data sources to track the far-reaching effects of the Russian war in Ukraine on global food insecurity. Sources included private shipping data from the MariTrace maritime intel company; Russian military data from the American Enterprise Institute Critical Threats Project; wheat import data from the International Grain Council; and UN databases for wheat production, price, and hunger data. Their source box provides a roadmap for investigating geopolitical drivers of hunger crises.

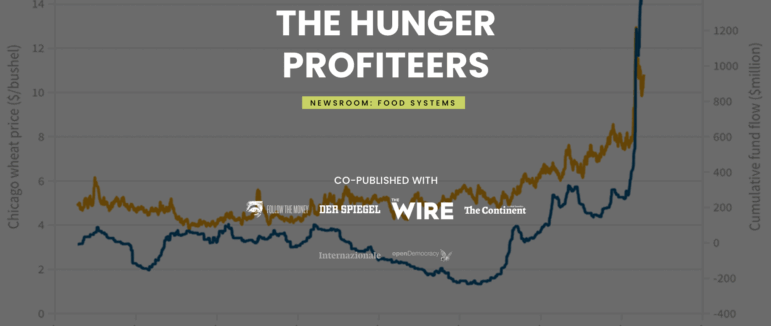

- The Hunger Profiteers, a 2022 Lighthouse Reports investigation, followed the money through publicly-traded agriculture funds to identify speculators cashing in on rising wheat prices during the war in Ukraine, then using public records laws to show how speculators lobbied regulators to look the other way. That story kicked off a series of revelatory reports on how pension funds fueled and hedge funds profited from the global food crisis. Each story includes a methods section with sources and insights into reporting on hunger economics.

This collaborative investigation looked into firms speculating on rising wheat prices due o Russia’s war on Ukraine. Image: Screenshot, Lighthouse Reports

Another emerging topic for investigation is whether food systems are ecologically and socially sustainable.

- Poison PR, a 2024 Lighthouse Reports investigation that included partners across five continents, combined freedom of information requests, money trails analysis, court records, and old-fashioned source building to expose a covert public relations campaign, partly funded by US taxpayers, to downplay the health and environmental risks of pesticides and discredit environmentalists and scientists in Africa, Europe, and North America.

- The Crimes Behind The Seafood You Eat, is the first installment of a 2023 multimedia series by the Outlaw Ocean Project published in The New Yorker and several dozen other international news outlets. The broader series was an investigation of China’s role in the global seafood trade. This first piece chronicled human rights and environmental crimes at sea on ships in the Chinese distant-water squid fishing fleet. The other parts in the series focused on land on the issue of state-sponsored forced labor in China’s seafood processing plants, particularly the use of North Korean and Uyghur workers.

An additional issue that deserves exploring is the quality of nutrition in the foods provided to satisfy the world’s hunger.

- How Nestlé Gets Children Hooked on Sugar in Lower-Income Countries, a 2024 investigation by Public Eye, a Swiss NGO, was picked up by major news outlets, and used a simple but effective method — laboratory testing — to show how the food conglomerate added sugar or honey to baby-food products sold in poor countries already struggling with obesity. Not only is this against international health guidelines, but it also represents a clear double standard: the same products available in rich countries do not have added sugar.

- McDonald’s Triumphs Over Councils’ Rejections of New Branches—by Claiming It Promotes ‘Healthier Lifestyles’, a 2025 investigation by The BMJ (British Medical Journal), used freedom of information requests to uncover the fast food giant’s tactics in parts of England where local governments were planning to restrict its presence. The corporation threatened legal action, argued its branches encourage healthier lifestyles, and provided references from an obesity expert who said McDonald’s food was healthy and nutritious.

The Green Revolution

The Green Revolution of the mid-20th century transformed agriculture in Asia and Latin America through mass production of cereals, meat, vegetables, and fruits.

It averted famine by introducing high-yield crop varieties, synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and irrigation, and is credited with saving millions from hunger and fueling economic growth in those parts of the world. US agronomist Norman Borlaug, often referred to as the “father of the Green Revolution,” won a Nobel Peace Prize “for his contribution to increasing food supply worldwide through the Green Revolution.”

Yet the gains came at a cost: ecological destruction from the reliance and overuse of chemicals, groundwater depletion, and a dangerous dependence on monocultures that erode biodiversity and farmers’ resilience. Wealthier farmers often benefited more, widening inequalities. Also, new technologies boosted yields but did so with practices that significantly raised agriculture’s greenhouse gas emissions by accelerating climate change, which in turn threatens future food production.

The Green Revolution’s legacy is now increasingly debated as an example of how technology may help feed the world, but how productivity without sufficient consideration for equity or sustainability can undermine long-term food security.

Hungry People at Merauke Food Estate, a 2022 investigation funded by the Pulitzer Center and published in Indonesia by Kompas, documented the cultural, health and environmental impacts of gastrocolonialism — the replacement of local food systems by low-quality and monoculture food imports implemented by the State’s nationwide program. The series includes tips for other journalists pursuing this issue in their own countries or communities.

Feeding the Congo Basin, funded by the Pulitzer Center and published in 2024 and 2025 by InfoNile, Mongabay, and others, investigated why the Congo Basin was experiencing one of the world’s worst food crises, despite fertile land, plentiful water and a large population of farmers.

What follows are some basic tips and resources for investigating hunger. The issue of starvation as a weapon of war is covered separately in a chapter of GIJN’s War Crimes Reporting Guide.

The Terminology

In reports from governments, the UN, and aid groups, hunger is usually described as “food insecurity” or “undernourishment.”

In 1996, the World Food Summit adopted the Rome Declaration on World Food Security, which said “food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.”

From this definition, experts further broke down food security into four main dimensions:

- Availability: is enough food being produced?

- Access: is the food actually available and affordable to people who need it?

- Utilization: can people make the most out of the nutrients in the food, not only through sufficient intake but also by ensuring the diet is diverse and carefully prepared?

- Stability: are the first three dimensions consistently followed?

It is also worth noting the differences between “chronic” and “acute” hunger.

- Chronic hunger is when a person is unable to consume enough food to maintain a normal, active lifestyle over an extended period. It is a long-term, persistent lack of sufficient nutritious food, and is usually caused by structural issues including poverty, inequality, weak food systems, and/or poor diets.

- Acute hunger is “when a person’s inability to consume adequate food puts their lives or livelihoods in immediate danger,” according to the World Food Programme. It is often triggered by shocks such as conflicts, natural disasters, or economic crises.

- Famine occurs where “at least one in five households has an extreme lack of food and face starvation and destitution, resulting in extremely critical levels of acute malnutrition and death.” The official determination is made by a UN-recognized hunger monitoring organization. See The IPC Famine Factsheet.

The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification System (IPC) and its partner, Cadre Harmonisé, assess the scale and severity of food insecurity in countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East that opt to participate. Countries are divided into regions that are rated on a one-to-five scale for acute food security and similar scales for chronic food insecurity and acute malnutrition. They provide a detailed explanation of the scales on their website.

Country reports are posted online and periodically updated by a team of experts and representatives from aid organizations in collaboration with the host governments. They help the UN World Food Programme and large international humanitarian nonprofits determine where and when to send what kind of assistance, such as food, medicine, seeds, or cash.

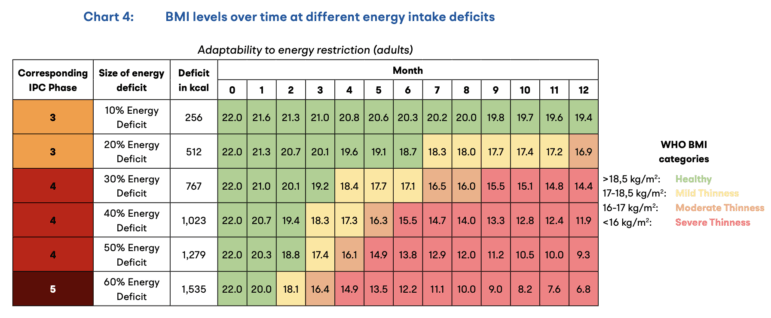

It’s important to note that, while famines are the worst outcome, each step on the IPC acute food insecurity scale represents an increase in excess mortality that can represent thousands of hunger-related deaths, depending on the size of the affected population. It’s also important to note that many of those deaths are caused not directly by starvation but because food deprivation can increase susceptibility and severity of a wide range of diseases. Chart 4 in From Hunger to Death, a report by Dutch think tank Clingendael, shows the effect of undernutrition on the human body by kilocalorie deficit and duration.

Chart of BMI levels over time at different energy intake deficits, from the 2024 “From Hunger to Death” report. Image: Screenshot, Netherlands Institute of International Relations

Tips for Investigating Hunger

The IPC numbers are only a starting point

While the IPC is an authoritative source, it should not be your only source. The acute assessments are heavily reliant on food, nutrition, and mortality data. Some see that as the system’s strength. But others consider it a major weakness at a time so many hotspots are in conflict zones, like Gaza and Sudan, where good data is difficult or impossible to collect. According to Reuters reports, in Gaza, “Israeli bombing and restrictions on movement have impeded efforts to collect statistics on malnutrition, deaths unrelated to trauma, and other essential data. In Sudan, violence, military roadblocks, bureaucratic obstruction and a telecommunications blackout have disrupted efforts to test for malnutrition, count deaths and survey people about their access to food.” The Reuters series includes a graphic explaining how the system works and where it failed in Sudan. See below for links to additional sources of data and information.

Lack of Availability Doesn’t Always Equate with Hunger

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, disrupting grain and fertilizer exports from two of the world’s biggest suppliers, on-the-ground impacts were dire, especially on poor households that spend a large proportion of their income on food.

But many news articles conflated two very different issues: accessibility with availability. True, Russia and Ukraine were responsible for between a quarter and a third of the world’s wheat exports, but what is available on the global markets is a fraction of global production. Much of the food produced around the world, including wheat, is consumed locally.

The main problem was that food prices had jumped while real wages declined, making food much more expensive. Countries reliant on imports for staple foods, due to years of agricultural policies that favored efficiency and yields, faced mounting bills to feed their populations. Food prices were already rising before the war due to both the COVID-19 pandemic and years of unpredictable production resulting from climate change.

Gaza is another example where the main cause of hunger is not that the crops have disappeared, but that there is a lack of access to food. Here, food exists but a combination of reduction in crops, exacerbated by Israel’s aid restrictions blocking food aid from neighboring countries and escalating food prices prevent people from accessing it.

Modern day hunger is often a result of political failure, not the unavailability of food.

Beware of “Hunger Washing” and “Feed the World” narrative

“Hunger Washing” is when politicians and profiteers seize on the fear of food shortages and the specter of hunger to push for certain policies that often oversimplify or misrepresent the causes of food insecurity.

For example, proponents often call for the expansion of industrial agriculture, boost the use of controversial technologies such as genetic modification and scrap environmental regulations and policies as ways to “feed the world.” They ignore deeper issues such as poverty, inequality, conflict, or poor governance that actually drive hunger. Similarly, political leaders may use hunger narratives to deflect responsibility or to garner support for trade deals, subsidies, or interventions that primarily serve powerful interests.

Also called “the cheaper food paradigm,” the underlying idea is the pursuit of cheaper, more abundant food with little consideration of side effects, including wiping out ecosystems, pollution and nutrient-poor foods.

These narratives use the moral urgency of fighting hunger but sideline the structural fixes truly needed to end it.

How the Meat Industry is Climate-Washing its Polluting Business Model, a 2021 DeSmog investigation into the meat industry’s PR and lobbying reviewed hundreds of documents and statements by companies and trade associations. It showed how an industry dominated by a handful of companies built a narrative around meat as indispensable to feeding the world, while questioning the science behind livestock’s outsize contribution to agriculture’s greenhouse gas emissions and minimizing meat production’s impact on both climate change and biodiversity.

Ask “Who Benefits?”

Just a few large corporations dominate activity at key points along global food value chains, and this consolidation and concentration of power can have a direct impact on whether people can afford daily meals.

Vertical, horizontal, and backward integration has allowed a few corporations to control our food systems. Some call this the “hourglass” structure, where a narrow chokepoint of corporate intermediaries oversee the flow of food between numerous small producers and consumers. This leads to unfair contracts for producers, abusive conditions for farmworkers, higher prices and more restricted access for consumers and vulnerable supply chains.

“The market power of the largest agribusinesses, coupled with weak or absent regulation of corporate political engagement, has paved the way for regulatory capture by certain agribusinesses looking to protect vested interests,” according to a report by Chatham House and UNEP.

See the Bigger Picture

Food systems is an encompassing term to describe the network of all actors, processes, and infrastructure connected to how food is grown, processed, distributed, consumed, and discarded. These include policies, economics, and environments that shape those interactions.

Globally, food systems are responsible for one third of total manmade greenhouse gas emissions that are heating up the planet, which then contribute to prolonged droughts, more intense and frequent storms and floods, and rising temperatures. These disasters can cause billions of dollars in losses for farmers, slash the harvests of essential crops, and lead to lethal working conditions for farm workers. Scientists have also warned that higher concentrations of carbon levels in the atmosphere can make crops less nutritious.

This means climate change is a threat to both the quantity and quality of future food production.

It is incomplete, however, to blame stubbornly high hunger levels to climate shocks. Currently, governments spend over US$460 billion a year supporting policies that are “inefficient, inequitable, distort food prices, hurt people’s health, and degrade the environment”.

Suggested Story Ideas

- How is your country or community measuring hunger? What parameters are being used and what are being ignored?

- What are the main drivers of hunger in your community? Is it really a lack of food or something else, like the unavailability or cost of healthy foods? If the latter, why is it this way and who is benefiting?

- Most governments subsidize agriculture. It is worth finding out exactly what they are subsidizing, why, and whether they will alleviate hunger and malnutrition in the community.

- A common criticism about these subsidies is that they encourage overproduction of resource-intensive crops and livestock, while healthier foods get very little support. Is that the case in your community?

- If you live in/near a farming community, it’s useful to understand what is being grown and for whom. Not all agricultural produce is for humans, or even animals. Some are used for industrial purposes.

- There is increasing interest in the health impacts of diets and how government policies (or lack of) could create conditions for hunger and malnutrition. The latest EAT-Lancet report has identified three types of food environments in urban areas: food voids (environments lacking in food), food deserts (areas where sufficient healthy food is inaccessible), and food swamps (areas where unhealthy and ultra-processed foods are abundantly available, accessible, and affordable). Do you live in one of those?

- The story series Emerging Hunger Hotspots highlighted rising food insecurity in middle-income countries that previously did not need humanitarian assistance and asked how they got there. It’s a good way to do a deep dive without embarking on a resource-intensive investigation.

- Another way to explore angles on hunger is by examining broader food systems issues. The three key and cross-cutting challenges concern making food systems healthier, greener, and fairer. Using these lenses can help identify gaps, trends, and the disconnect between political rhetoric and reality on food insecurity.

- Structural inequalities and power imbalances play a key role in whether a community is food secure or not. This quote, from the 2021 UN Food Systems Summit, is worth remembering when digging into hunger stories and numbers: “Unequal relationships and power dynamics in markets, in households, and in policy processes, determine who has access to resources and who does not, shaping who is hungry and malnourished and who is not.”

Tools for Covering Hunger

Key Reports

- The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) is the annual report from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) together with four fellow UN agencies. It provides global data on chronic hunger from the previous year. Once the global report is published, the data is disaggregated into regional reports that are then published a few months later.

- Hunger Hotspots are biannual reports from the Global Network Against Food Crises, a network of humanitarian and development organizations. It focuses on acute hunger.

- It is also worth checking the national statistics offices of individual countries for more up-to-date figures. They often release rapid survey data or situational reports before the FAO consolidates them in SOFI.

Getting the Data

- Integrated food Security Phase Classification System (IPC): The authoritative international body for assessing the scale and severity of food insecurity in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Middle East.

- IPC Country Analysis of current food crises

- IPC Technical Manual Version 3.1

- CH Cadre Harmonisé (West Africa)

- United Nations

- OCHA Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs: Umbrella UN agency overseeing humanitarian fundraising and food aid distribution.

- ReliefWeb Document and data repository for humanitarian crises

- WFP World Food Program World’s leading food aid distributor

- Annual Country Reports 2024 | World Food Programme

- World Food Programme Vulnerability Analysis and Mapping: The Emergency Dashboard has a monthly visual overview of WFP’s work in some of the worst hunger hotspots. The Economic Explorer has market price bulletins, price comparisons, and exchange rate data on a handful of countries in Africa, Asia, and South America.

- FAO Food and Agriculture Organization (includes Global Information and Early Warning System on Food and Agriculture (GIEWS): monitors food supply, demand, and other key indicators to assess global food security. Produces the biannual Food Outlook, location-specific reports, and regional and national alerts.

- FAOSTAT Suite of Food Security Indicators: the data portal of FAO with a list of indicators on food insecurity, overweight, obesity, dependency on food imports, at global, regional, and country levels going back to the year 2000

- iRHIS | Integrated Refugee Health Information System UNHCR data, stats on refugee camp nutrition, health, etc.

- Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates (JME) 2025 UNICEF, WHO and World Bank produce annual estimates for child stunting, overweight, underweight, wasting and severe wasting. Past reports, data and interactive tools are available at the website.

- European Commission Knowledge Centre for Global Food and Nutrition Security provides links to tools and datasets for tracking food insecurity, crises and leading drivers — including armed conflict, displacement, crop anomalies and disasters.

- SMART Interagency organization that conducts surveys on nutrition and mortality for humanitarian organizations

- Food Systems Dashboard uses existing data from multiple sources to track 50 indicators across five themes on the state of food systems transformation.

- USAID country ”complex emergency reports” track and offer analyses of emerging food crises in conflict zones, Existing reports, as of this writing, were still available at foreignassistance.gov.

Resources to Track Food Prices

- Agricultural Market Information System (AMIS): G20 members, along with Spain and eight major exporting and importing countries of agricultural commodities. Accounts for 80%-90% of global production, consumption and trade volumes of wheat, maize, rice, and soybeans. The Market Monitor tracks international prices, futures markets and prices of fertilizers and vegetable oils.

- FAO Food Price Index (FFPI): Tracks monthly changes in international prices of a basket of food commodities (cereals, vegetable oil, meat, dairy, and sugar). Released at the beginning of the month.

- IFPRI’s Food Security Portal: Provides global-level data on the volatility of food commodities, fertilizers, and energy and the prices of maize, rice, soybean, and hard and soft wheat. There is an expanded list of crops for Sub-Saharan Africa, and a more limited one on Asia-Pacific. Glitchy.

- World Bank data on commodity markets: Monthly updates of the prices of food and agricultural commodities, shows annual, quarterly, and monthly averages for easy comparison. Also includes non-food items.

- African Market Observatory (AMO) Price Tracker: A monthly price tracker summarizing key trends in East and Southern Africa on the prices of selected staple foods. You can sign up here for alerts.

- AGRA Food Security Monitor (Africa)

- ASEAN Food Security Information System (AFSIS): Publishes the biannual reports Agricultural Commodities Outlook (stocks, production levels, imports, etc) and Early Warning Information (on staple foods). There is country-level production data. Glitchy.

- Eurostat Food Price Monitoring Tool: Monthly data on consumer and producer price indices either as overall “food” or 26 food categories you can choose from. Note: Shows indices that track overall performance of assets , not prices.

- USDA Data Products | Economic Research Service: Food security datasets

Resources to Track Humanitarian Funding and Spending

- Financing Flows and Food Crises is an annual publication of how much and where the money is going to tackle food crises, organized by geography, recipient country and sectors.

- ReliefWeb is an information platform run by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). It provides reports, press releases, maps, and infographics on global humanitarian crises.

- OCHA Financial Tracking Service offers data on funding flows on humanitarian crises around the world. For each country it is monitoring, it tracks the progress as well as where the money is coming from and where it is going.

Selected International NGOs

- Action Against Hunger

- AGRA (formerly Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa)

- BRAC International

- Bread for the World

- CARE International

- Danish Refugee Council

- Global Alliance against Hunger and Poverty

- Heifer International

- Hunger Project

- International Committee of the Red Cross

- International Food Policy Research Institute, part of the CGIAR network of 14 global agricultural research centers

- Médecins Sans Frontières

- Mercy Corps

- Norwegian Refugee Council

- Oxfam International

- Partners In Health

- Relief International

- Save the Children

- WhyHunger

- World Vision

Global Investigative Journalism Network Resources

- Investigating War Crimes: Starvation

- Resources on Food and Agriculture

- Investigating Food Supply and Agriculture Amid Climate Change

- Resources for Finding and Using Satellite Images

Thin Lei Win is the lead reporter for the Food Systems Newsroom of Lighthouse Reports and curates her food systems newsletter Thin Ink. She also co-founded Myanmar Now, a bilingual news agency, and The Kite Tales, a non-profit storytelling project focused on Myanmar.

Thin Lei Win is the lead reporter for the Food Systems Newsroom of Lighthouse Reports and curates her food systems newsletter Thin Ink. She also co-founded Myanmar Now, a bilingual news agency, and The Kite Tales, a non-profit storytelling project focused on Myanmar.

Deborah Nelson is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and professor of investigative journalism at Philip Merrill College of Journalism, University of Maryland. She was part of an international team at Reuters that produced The Starving World, a 2024 series that examined the global hunger relief crisis.

Deborah Nelson is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and professor of investigative journalism at Philip Merrill College of Journalism, University of Maryland. She was part of an international team at Reuters that produced The Starving World, a 2024 series that examined the global hunger relief crisis.