Drone footage of wastewater flowing from an industrial copper mine. The orange soil is contaminated with heavy metals. Image: Shutterstock

Tips for Investigating Green Energy Supply Chains in the Global South

Read this article in

In recent years, investigative journalists have made a significant impact exposing labor and environmental abuses by the fossil fuel and palm oil industries. But noticeably less scrutiny has been given to extractive industries providing the resources for solar panels, electric car batteries, and other alternative fuel components.

Despite the climate benefits of renewable energy and the United Nations insistence that “human rights must be at the core of all mineral value chains,” each year, new resource extraction projects in the Global South exploit local communities or launch without their input, damaging local ecosystems and collectively displacing hundreds of thousands from their homes.

These harms range from less obvious risks, such as toxic waste tailings dams perilously located just upstream of villages inside earthquake zones, to more brazen — including the forced labor practices behind some solar cell components, the deforestation connection to new car models, and a loss of clean water access for Indigenous communities. In addition, end users of these affected supply chains typically have little to no visibility of the human costs and problematic origins of the green energy products they are enthusiastically embracing. Sometimes these distant consumers may even be the targets of savvy greenwashing campaigns, pushing misleading information about the extraction of critical raw materials such as bauxite, cobalt, rubber, and lithium.

According to the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre, the accelerating demand for these resources is “pushing both producing and importing countries to prioritize access over safeguards, accelerating mining approvals and downplaying social, environmental, and human rights concerns.”

The good news is that investigative reporters can freely use several powerful investigative tools, originally designed for civil society groups, to hold various actors accountable for these harms — from Global South mining firms to the major Western brands they supply.

In a session on investigating the impact of alternative energy at the recent Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE) conference in the US, a panel of experts revealed that a combination of direct reporting on affected communities plus deep supply chain research was the best formula for achieving impact. That’s not only because of the pressure that name-brand alternative energy manufacturers can exert on minerals suppliers and middlemen to limit the fallout of reckless extraction practices, but also because customers can spark public outrage over the faraway lives and ecosystems ruined to enable their green products.

The IRE panel included Annie Burns-Pieper, freelance investigative reporter and deputy research director at the human rights NGO Inclusive Development International (IDI), B. Toastie Oaster, an award-winning Indigenous affairs journalist at High Country News, and Sheridan Prasso, a senior writer for investigations at Bloomberg.

Prasso produced a classic supply chain investigation in this area in 2023, which traced much of the aluminium in a major US electric vehicle model to a refinery that has been blamed for sickening thousands of people in the Amazon, and to a mine linked to deforestation and land grabs. In March, she and her colleagues exposed serious labor rights violations at rubber and palm oil plantations in West Africa, including allegations that women working there routinely face demands for sex in exchange for employment. She showed how these plantations ultimately supply major Western tire and food brands.

Bloomberg investigated the links between famous Western brands and labor abuses at West African rubber plantations. Image: Screenshot, Bloomberg

Prasso said major brands at the consumer-facing end of supply chains typically rebuff these kinds of investigations by simply saying: “We follow the law.” But she urged journalists not to be dissuaded by mere proof of regulatory compliance.

“Following the law is not the same as being unaccountable for harm at the other end of supply chains,” she explained, adding that many corporations also have social and environmental policies that might conflict with supplier behavior.

Using Civil Society Resources for Supply Chain Investigations

The nonprofit group IDI works directly with grassroots organizations and global communities affected by the extractives industry to help defend their rights. And Burns-Pieper confirmed that the group is glad to connect journalists to these hard-to-reach sources in often remote parts of the world, offering a reporting channel that could potentially provide a bounty of contacts and story ideas.

“I feel that supply chain stories connected to the energy transition are under-covered,” said Burns-Pieper. “People are a little intimidated by this area, but there are some great tools that can really get you going. We at IDI have investigated more than 300 harmful projects since 2016 — largely mining-related — and we work with groups all over the world, and we’ve been training people in civil society to do this research themselves, so we can put reporters in touch with communities abused at the end of these chains.”

Prasso vouched for the intrinsic value of this global networking, adding: “I can’t do my work without the connections provided by groups like IDI.”

“Most of this research is done using publicly available free sources, and just takes knowing where to look,” Burns-Pieper explained. “Try to step back and look at how this mineral usually gets to market, not specific to your project, but generally. Google the commodity and the word ‘supply chain’ and look at the images, and you can often see the basic steps the mineral takes; that’s useful for finding the types of actors involved.”

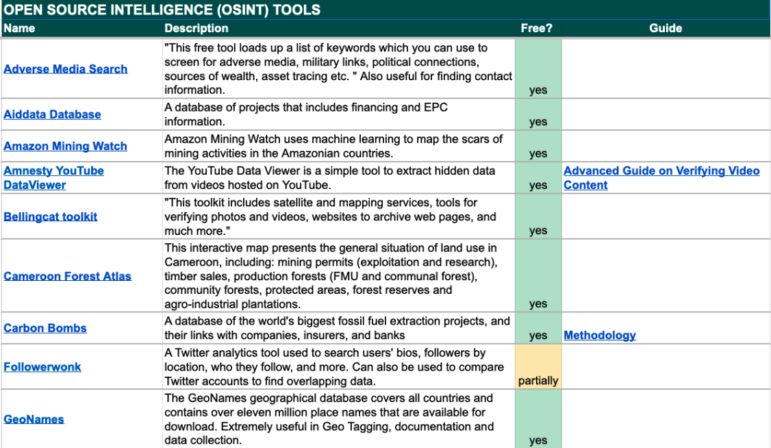

She added: “This work requires creative investigative research. I start with advanced Googling — seeing if I can connect the mining company with the major end-users — and then there are other ways, such as company disclosures, media reports, expert databases, OSINT tools, Google Pinpoint, and Google Images.”

Burns-Pieper also shared a comprehensive list of civil society research tools that investigative reporters can freely access (but rarely take advantage of):

- Follow The Money Toolkit. This vast treasure trove of free tools and databases from IDI lets reporters dig into every aspect of corporate harm in the Global South, and features open source research tools, corporate registries, and even pension fund disclosures. Databases range from Land Matrix — a dataset of global land deals — to the Chinese Loans to Africa Database as well as the GIJN Resource Center.

Snapshot of the resources listed in the Inclusive Development International’s Follow the Money Toolkit. Image: Screenshot

- BankTrack. This tool offers several resources that profile the financial institutions funding potentially harmful corporate projects in vulnerable places, particularly in the Global South. Run by a civil society advocacy nonprofit in the Netherlands, the platform includes a ‘Dodgy Deals Database’ that is described as a “one-stop information source” on the financing of projects deemed to be harmful to society or the environment by civil society partners. Caution: Most of the scores of case profiles are contributed by civil society campaigners, and BankTrack freely concedes that the database is not comprehensive, and that facts on the deals and projects need to be independently verified. However, Burns-Pieper said the tool can be an excellent source of leads for journalists to check, follow, and develop.

- Business and Human Rights Resource Centre Company Index. This resource allows reporters and researchers to search the track records of more than 20,000 companies on social and environmental issues, based on reported news and allegations of harm. It also includes a new company dashboard that offers additional financial and policy data on 142 extractive industry firms and 144 tech companies.

- Just Transition Litigation Tracking Tool. Also hosted by the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre, this is a database of community or civil society lawsuits against companies undertaking key mining or renewable energy-related extraction projects, or against states authorizing them. “It’s useful that they’re tracking litigation on this issue, and it’s a resource for journalists to find contacts,” said Burns-Pieper.

- Environmental Justice Atlas. EJAtlas documents socio-environmental conflicts involving harmful economic activities across the globe, recording more than 4,300 conflicts to date. It allows users to filter for commodities, and to zoom into specific regions.

- FollowingTheMoney.org. This is a major resource from IDI that includes the Development Bank Investment Tracker, which includes records for almost 300,000 project investments by 17 development finance institutions, the Shareholder Tracker, and a PalmWatch tool, which maps global palm oil supply chains and the major Western brands they supply. It also features original harm investigations, and a practical guide to supply chain research. “It’s a research guide developed for civil society, but it works just as well for reporters,” Burns-Pieper added.

Connecting Brands with Global South Harms

“Regarding AI, I have not had any luck using LLMs for supply chain research, though this is probably coming,” said Burns-Pieper. “But I find Pinpoint really helpful. I will do a batch download or scrape of corporate documentation — from a company website or SEC filings — then I’ll dump that all into Pinpoint, and that will pick out the names of organizations in those documents, and you can see if there are any big brands named, or any middlemen involved.”

Annie Burns-Pieper is a freelance investigative reporter and IDI’s deputy research director. Image: Screenshot, LinkedIn

She added: “Pinpoint also now has the Gemini feature, where you can ask it questions about what’s in your documents. I asked Gemini ‘What car companies are mentioned in this documentation?’ and it pulled out all the car firms.” Once verified, this information could offer a reporter numerous story angles.

Other green energy investigations worth pursuing include tracing the provenance of components from certain companies in China and other authoritarian nations that are banned from Western markets due to allegations of forced labor. Despite the restrictions, these raw materials can still find their way into those markets — and even into public utilities — via middlemen, or in the form of finished products manufactured in other countries.

“The idea is to find the connective tissue, and a lot of what I do involves import-export records to link supply chains to particular companies,” Prasso explained. Key tools that Prasso uses include:

- ImportGenius – a searchable subscription-based service with detailed US import-export records, that offers data from other countries for an additional charge.

- 52wmb.com – a more affordable database that includes data on product types, quantities, and prices from 32 countries.

- Sayari – a subscription-based supply chain research tool that shows connections between companies, and sometimes provides journalists with additional data in exchange for citation, according to Prasso.

- ImportYeti – a less comprehensive but entirely free database that allows researchers to find suppliers via a database of 70 million US sea shipment records.

“I also find knowing the major end-users of something is really helpful; in knowing that a collection of major car manufacturers are responsible for using a particular mineral — that’s going to help your supply chain work,” said Burns-Pieper.

“This is not an exact science,” she acknowledged. “It’s going to be hard to find all of the exact customers connected to a particular project or company. There are few disclosure requirements for these things; these agreements are often protected by commercial secrecy rules and there will be gaps in information. A realistic goal is to gather enough credible evidence to question the companies involved.”

Rowan Philp is GIJN’s global reporter and impact editor for GIJN. Rowan was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is GIJN’s global reporter and impact editor for GIJN. Rowan was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.