Understanding the Authoritarian’s Playbook: Tips for Journalists

Read this article in

The hallmarks of populist nationalism are gaining ground in many of the world’s largest democracies from Modi’s India to Bolsonaro’s Brazil and Trump’s America. In these, and many other countries, elected leaders are flirting with aspects of authoritarianism in an extreme era of digital disruption, mass migration, and the mounting effects of climate change.

The hallmarks of populist nationalism are gaining ground in many of the world’s largest democracies from Modi’s India to Bolsonaro’s Brazil and Trump’s America. In these, and many other countries, elected leaders are flirting with aspects of authoritarianism in an extreme era of digital disruption, mass migration, and the mounting effects of climate change.

In this project, Democracy Undone: The Authoritarian’s Playbook, GroundTruth reporting fellows in India, Brazil, Colombia, Hungary, Poland, Italy, and the United States chronicled how seven nationalist leaders in each of these countries seem to be working from the same playbook.

It is a playbook that our reporting team has pieced together from the speeches and techniques in use by an interconnected web of populist leaders and their strategists as a way to gain power, impose their values, and implement their agenda. The reporting is not intended to suggest that each of these countries is now under an authoritarian regime, but that their leaders are showing instincts and inclinations that lead to a brand of populist nationalism that, if history is a guide, can lead to authoritarian government. Scholars on democracy say they seem eager to join China, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and other leading authoritarian states in stamping out democratic protections and reshaping the global order.

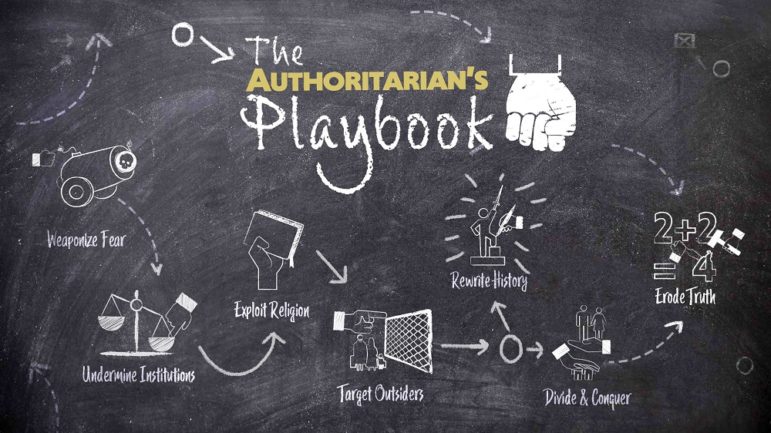

Key ‘Plays’ in the Playbook Include:

Weaponize Fear – Embrace a language of violence, promote a more punitive culture, leverage military might at home. Give critics reason to believe they’ll be harmed if they oppose.

Target Outsiders — Stoke the fires of xenophobia by demonizing immigrants and foreigners. Blame domestic problems including economic woes on these scapegoats, and depict political opponents as sympathetic to these imagined enemies.

Undermine Institutions — Take over the courts, eliminate checks and balances, undo established treaties and legislation that limit executive power, weaken protections for free and fair elections.

Rewrite History — Exert control over schools and the media to indoctrinate the public with beliefs that reinforce autocratic power.

Exploit Religion — Appeal to the religious majority while targeting minorities. Conflate national identity with religious identity.

Divide and Conquer — Use hate speech and encourage violent actors to widen social rifts and use manufactured crises to seize more power.

Erode Truth — Attack the press as an “enemy of the people;” dismiss negative reports as “fake news,” counter legitimate information with disinformation or “alternative facts.” Blast the media landscape with endless scandal and contradiction to overwhelm the traditional fail-safes.

One common thread in the global implementation of The Playbook? Steve Bannon, a US naval officer turned Goldman Sachs banker turned right-wing media executive, Trump advisor, and Cambridge Analytica board member.

As part of what he calls “The Movement,” Bannon’s influence is evident in populist parties across Europe, South America, and Asia. Cambridge Analytica alone played a major role in the recent elections of the US, Brazil, UK, India, and the Philippines, using targeted social media campaigns based on sophisticated user data to startle voters and push outcomes toward populist candidates and illiberal ideas. But sophisticated algorithms aren’t necessary to participate: Paid and unpaid propagandists of all stripes can spread misinformation both knowingly and unknowingly on Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, and other platforms, shifting public opinion in a way once reserved for government agencies and major media outlets.

Another common thread? President Trump himself. He has pursued warm relationships with the six leaders profiled in this project as well as with autocrats like Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey, King Salman in Saudi Arabia, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in Egypt, Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, Kim Jong Un in North Korea, and of course, Vladimir Putin in Russia.

From holding hands with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi at a “Howdy, Modi!” rally in Houston last month, to offering quick congratulations to Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro after his election victory, and offering a warm White House reception to Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán in May, Trump gravitates toward a certain kind of leader.

He’s spearheaded unprecedented collaboration with authoritarian leaders on foreign policy, including a Trump deal with Turkey to permit a military incursion into northeast Syria, putting America’s longtime Kurdish allies in grave danger and providing the Russian and Syrian governments with more leverage there, along with a whitewashing of the Saudi government’s murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi while sending thousands of additional US troops into the Kingdom.

Trump’s alliances and his actions at home fail what scholars Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt call “a litmus test for autocrats” in their 2018 book “How Democracies Die.”

The four criteria are:

- Rejection of (or weak commitment to) democratic rules of the game

- Denial of the legitimacy of political opponents

- Toleration or encouragement of violence

- Readiness to curtail civil liberties of opponents, including media

By Levitsky and Ziblatt’s analysis, Trump meets all four criteria, the first American president since Richard Nixon to fulfill even one of these conditions.

As part of what author and scholar Sarah Kendzior calls “authoritarian kleptocracy,” the Trump administration’s alliances enrich a small group of leaders and their cronies while attacks on democratic institutions, including the free press, provide cover for repressive rulers around the world.

In just one instance, Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad dismissed an Amnesty International report detailing as many as 13,000 extrajudicial killings by Assad’s regime at the Seydnaya Prison between 2011 and 2015 by saying, “You can forge anything these days. We are living in a fake-news era.”

As Arturo Sarukhan, former Mexican ambassador to the United States, said on Twitter, “What happens to democracy in the US reverberates globally. Trump’s further erosion of democracy would have a domino effect felt around the world.”

Democracy is fragile, and susceptible to attack from the inside. Drawing strength from economic resentment and underlying prejudice, populist authoritarian leaders have a knack for turning election victories into mandates to dramatically reshape power structures that reinforce the power of the few over the many. That paradox is explained by Jan-Werner Müller, a political scientist at Princeton University, in his 2016 book What Is Populism?

“In addition to being anti-elitist, populists are always anti-pluralist. Populists claim that they, and they alone, represent the people,” Müller wrote.

In accepting the presidential nomination at the Republican National Convention, for example, President Trump proclaimed. “Nobody knows the system better than me, which is why I alone can fix it.”

But the logic goes deeper, with insinuations and outright proclamations that certain groups are more entitled to the resources and protections of the country.

In authoritarian governments and those leaning in that direction, even the veneer of protecting all of the people is ripped away, opening the door for mass incarceration, police and military executions, and new laws limiting the freedom of religious and ethnic minorities. Mass displacement in regions destabilized by violence, economic weakness, and climate disruption only exacerbates this process, while those same leaders deny the science confirming climate change.

In a piece for the South China Morning Post, GroundTruth fellow Soumya Shankar reported that some of India’s most extreme Hindu nationalists have found kindred spirits in white supremacists worldwide over a shared hatred of Muslims.

Hate crimes against Muslims, Christians, and Sikhs have skyrocketed during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s tenure, according to a University of Massachusetts-Amherst study. And a dramatic policy shift on the contested region of Jammu and Kashmir led to a violent and ongoing lockdown in the Muslim-majority region.

“With the coming of Modi, people know they can get away with violence, and are more vocally Islamophobic on social media,” journalist Kashif-ul Huda told GroundTruth’s Shankar. Meanwhile the most zealous Modi supporters have launched sustained online harassment campaigns against political opponents and journalists including Shankar.

Harsh Shringla, then India’s ambassador to the US, met with Steven Bannon in September briefly posting a photo celebrating Bannon as a “legendary ideologue and ‘Dharma’ warrior,” apparently a reference to a 2017 profile that explained Bannon’s worldview in terms of the Hindu concept of “duty” and an imagined return to dominance of traditional social values.

In Brazil, where GroundTruth fellow Letícia Duarte is reporting, a violent nationalist resurgence led by President Jair Bolsonaro is targeting political progressives, indigenous Amazonian tribes, and journalists alike.

Bolsonaro, like Trump, is given to referring to the press as the “enemy of the people,” and has his own Bannon-like advisor, a man named Olavo de Carvalho who helped provide Bolsonaro with the rhetorical key codes and online following he needed to win.

Olavo met with Trump and Bannon in Washington, DC in March. At a dinner hosted by the Brazilian ambassador, Bolsonaro said his dream was “to set Brazil free from the nefarious leftist ideology.” Turning his eyes to Olavo, he said, “The revolution we are living, we owe in large part to him.”

Speaking at an event honoring him with Brazil’s highest diplomatic award in August, Olavo bragged, “My influence on Brazil’s culture is infinitely bigger than anything the government is doing. I am changing Brazil’s cultural history. Governments go away, the culture stays.”

The language is familiar. Former Cambridge Analytica staffer Christopher Wylie, testifying before Congress last May as a whistleblower who had an inside perspective on how the company scraped Facebook data to create social media campaigns to help elect Trump, said Bannon “saw cultural warfare as a means to create enduring change in American politics.”

Soon after leaving his post as Trump’s advisor in the wake of the violent white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, where one protester was killed, Bannon shifted his efforts to Europe, working closely with Hungary’s Orbán and Italian far-right leader Matteo Salvini, who until recently held the respective positions of deputy prime minister and minister of the interior.

“I have an exceptional relationship with Salvini, I think he and Viktor Orbán are the two most important politicians in Europe today,” Bannon told El País in March. “More than Trump, he and Salvini defend the idea of a Judeo-Christian West. And it is something that is also close to Vox [Spain’s right-wing nationalist party]: traditional family, society structure, war against cultural Marxism … Remember that this movement is populist, nationalist, and traditionalist. And Bolsonaro and Salvini are their best representatives,” added Bannon.

A shift against liberal democratic values and the global institutions that have reinforced them is underway, with Bannon and his allies proving remarkably successful. His “culture war,” fueled by the internet and the media echo chambers it fuels, is becoming a dominant global paradigm.

And though leaders like Modi, Bolsonaro, Orbán, Kaczyński and Trump are democratically elected, populist authoritarians seize hold of the levers of democracy and turn the machine in on itself to satisfy their own ends. As believers in a more pluralistic world evaluate their next moves and how best to counter the rise of populist nationalism across the globe, they might do well to study The Authoritarian’s Playbook.

Tips for Journalists Covering Rising Authoritarianism

Holding government officials accountable and reporting on complex policies is no small challenge, but when a democracy is under attack by its own leaders, it becomes particularly difficult, even dangerous. Journalists often need to be more resourceful and prepared when dealing with sources like these, and more careful when approaching people both in person and online.

These considerations were foremost on our mind when we dispatched eight journalists to seven countries to report on how world leaders seem to be drawing from the same “playbook” to undermine the democracies that elected them. Our fellows produced a series of articles and podcast season that not only map these dubious tactics, but revealed the challenges of reporting under these circumstances.

For this installment of Navigator, we asked these reporters to reflect on their experiences. Here, they offer tips and advice to other journalists covering places where democracy is being undone. Their responses have been edited for length and clarity.

What practical advice would you give to journalists who are pursuing stories in countries where democracy is being eroded?

1. Research your subject’s methods

Study your subject carefully before going for any interview. Attacking the press and trying to discredit journalists is one of the first tactics these leaders use, so we have to be extra prepared to recognize it and avoid feeding the cycle. It’s not just about studying their ideology and biographies, but also about their tactics on intimidating the press and distorting reality.

– Letícia Duarte, GroundTruth Fellow, Brazil

2. Do a risk assessment (for online and offline threats)

Be prepared to tackle and defeat trolling, threats, and in some cases, actual violence. Know that your reporting may be twisted, misread, misinterpreted within the polarized ecosystems of faltering democracies. Do a risk assessment with your editors and peers, take all the necessary precautions.

– Soumya Shankar, GroundTruth Fellow, India

3. Be conscious of how people view their own country

When you’re going in to interview people in countries that have made headlines worldwide for the reckless actions of their leaders, bear in mind that the local population is quite sensitive to the way their country, including its people, are portrayed internationally. I’ve had people come to me and say “I live a decent, honorable life and worked hard to earn what I have — why does that mean one thing in the country I happened to be born in and something else in a developed country, like the United States?”

People feel like you’re personally blaming them for what their country is going through, and that makes it harder for you to gain their trust and conduct productive interviews. I’m amazed at how good journalists from developing countries are at talking to subjects from other developing countries, even though the respective countries happen to be worlds apart and completely different! Of course, this refers to the average people that you might interview, not politicians. You can blame the politicians for the situation in the country.

– Una Hajdari, GroundTruth Fellow, Poland

4. Understand your role/responsibility as a journalist

Often, what these guys want is to invite journalists to a fight. Don’t take it personally, don’t overreact. Keep focused on your questions, and pay attention to each detail, so you can describe it later to your audience. Finally, be sure to record and document everything in as much detail as possible, because they will probably later accuse you of spreading “fake news.”

– Leticia Duarte, GroundTruth Fellow, Brazil

5. Create a reporting plan

I think the most important thing is to really work out from A to Z your reporting plan beforehand. Things could (or will) evolve overtime, so you need to be able to pivot your research, reporting, aim. You need to be a bookworm about the country (including on any press regulations, knowing your rights as a visitor, organizations that could be of help). If you come from abroad, like I did, test your ideas and angles with sources, analysts, colleagues to get leads. Foreign diplomats in the country are also often useful.

Pick a good fixer, preferably fluent in your native language, with a journalism background. Always be honest with sources, even if they are becoming antagonistic (sometimes, it is for show). And if you are interviewing officials on the record or off, triple-check your facts and figures.

– Quentin Ariès, GroundTruth Fellow, Hungary

6. Use public events to your advantage

Another tip relates to getting quotes from politicians, leaders of movements, or just about anyone who is not known for having a transparent relationship with the press. I’ve found that it is easier to get a quote from someone who usually wouldn’t react to press inquiries from papers they deem to be “critical” or “not on their side” if you go to a public event that they’re organizing. These people usually love attention, and it’s easier to ask them a question at a seemingly unrelated event where they won’t be expecting it.

I love going to events marking anniversaries or events inaugurating a new school or initiative. Their press people won’t be expecting critical questions and you’re more likely to get a turn. They might get angry at you, but that in and of itself is a reaction. If they completely ignore your question, try to get an aide or someone who is at the location with them — these people want to seem like they’re open to the press and might give you a quote you can use.

– Una Hajdari, GroundTruth Fellow, Poland

7. Free yourself from assumptions

More than advice, I would like to share a warning about bias: I felt I had the tendency to report about the shrinking of the public debate in Italy and the consequent erosion of democracy using an outdated lens and categories (as in using old-style labels like Fascism). I realized it was unfair and inaccurate during the reporting process. Approach the movements and people you meet with fresh eyes to better understand what they believe in.

In the Italian case, where authoritarianism is less brutal and less evident compared to what Soumya, for example, reported in India, it is important to delve deep in the narrative of the authoritarian movement. Logic traps, loopholes, and contradictions are features of every political ideology, but they are particularly abundant in these current authoritarian movements. The best way to get to the story is through the characters’ own words, but you have to find the right characters to interview. Militants who are still “behind the scenes” are a great resource. For example, Luca Toccalini was the perfect character for us because he was unknown to the audience but well-regarded in the inner circle of the Lega.

– Lorenzo Bagnoli, GroundTruth Fellow, Italy.

These articles were first published by The GroundTruth Project here and here and are reproduced here with permission. This Democracy Undone project was produced by The GroundTruth Project, with support from the MacArthur Foundation and the Henry Luce Foundation. Subscribe to any of GroundTruth’s newsletters here or follow them on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

Kevin Douglas Grant is The GroundTruth Project’s co-founder and chief content officer, as well as vice president of Report for America. He was previously senior editor of Special Reports at GlobalPost, led reporting projects around the world and his work has been recognized by the Edward R. Murrow, Alfred I. duPont-Columbia University and Online Journalism Awards among others.

Kevin Douglas Grant is The GroundTruth Project’s co-founder and chief content officer, as well as vice president of Report for America. He was previously senior editor of Special Reports at GlobalPost, led reporting projects around the world and his work has been recognized by the Edward R. Murrow, Alfred I. duPont-Columbia University and Online Journalism Awards among others.