Two workers wearing protective clothing, goggles and masks are disinfecting Wang Si's house.

Editor’s Pick: 2019’s Best Investigative Stories from China

It’s been a tough year for investigative journalism in China. At the beginning of the year, President Xi Jinping visited the People’s Daily, the Chinese Communist Party’s official newspaper, and underscored the need to strengthen “mainstream public opinion” and “mainstream values.” In the party’s use of the word, “mainstream” is something that can be manufactured and controlled — code for media control and censorship.

When I asked journalists in mainland China to recommend good investigations they’ve come across this year, many of them asked a question in return: Is there still any investigative journalism in China? In some ways, they are right — there are fewer and fewer investigations being published today. But this doesn’t tell the full story: There are still some hard-working investigative journalists in China doing serious investigations, although the environment they are working in keeps getting more difficult. These investigations are like wild plants surviving in the cracks, persistent and powerful.

As part of the GIJN Editor’s Pick series for 2019, below are some of the best works of investigative journalism from China in 2019, as selected by the GIJN Chinese team.

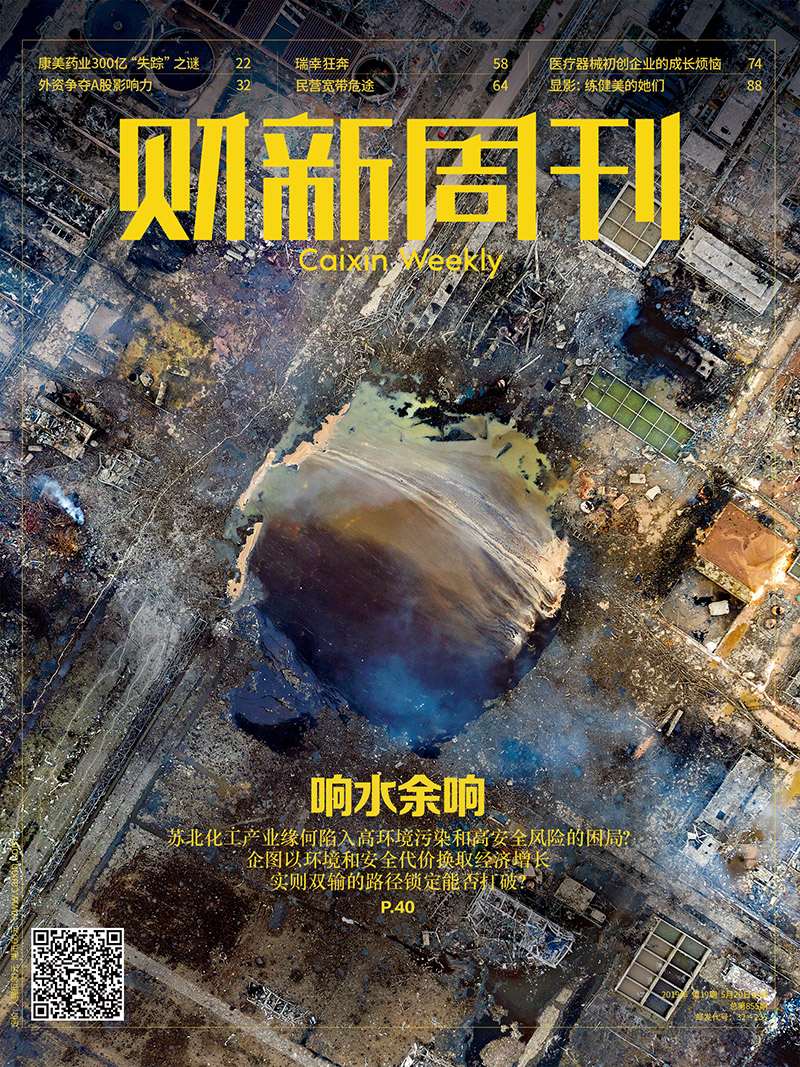

Chemical Plant Explosion

On March 21, a major explosion occurred at Jiangsu Tianjiayi Chemical Plant in Yancheng’s Chenjiagang Industrial Park. The explosion was so powerful that the China Earthquake Administration reported a magnitude 2.2 earthquake. The blast caused the deaths of 78 people and injured 617.

Many journalists traveled to Xiangshui to cover the story right after the explosion, but due to censorship, many of the initial stories were banned. Two months later, when control over coverage of this incident loosened, Caixin, one of China’s most influential financial media outlets, published an in-depth series about the explosion. It focused on one question: How did it happen? Caixin interviewed residents living near the chemical plant, chemical professionals, and government officials. Its report unraveled the root causes of the explosion: To boost economic development, the local government encouraged many factories to invest in the area, but the supervision was weak. This highlighted the Chinese chemical industry’s dilemma between prioritizing economic development or environmental protection.

Phoenix New Media, a leading news outlet in China, also ran a great story about the explosion. Its reporters interviewed seven victims of the blast, using photos and videos to tell their stories. These touching, powerful portraits show how the explosion destroyed individuals’ lives.

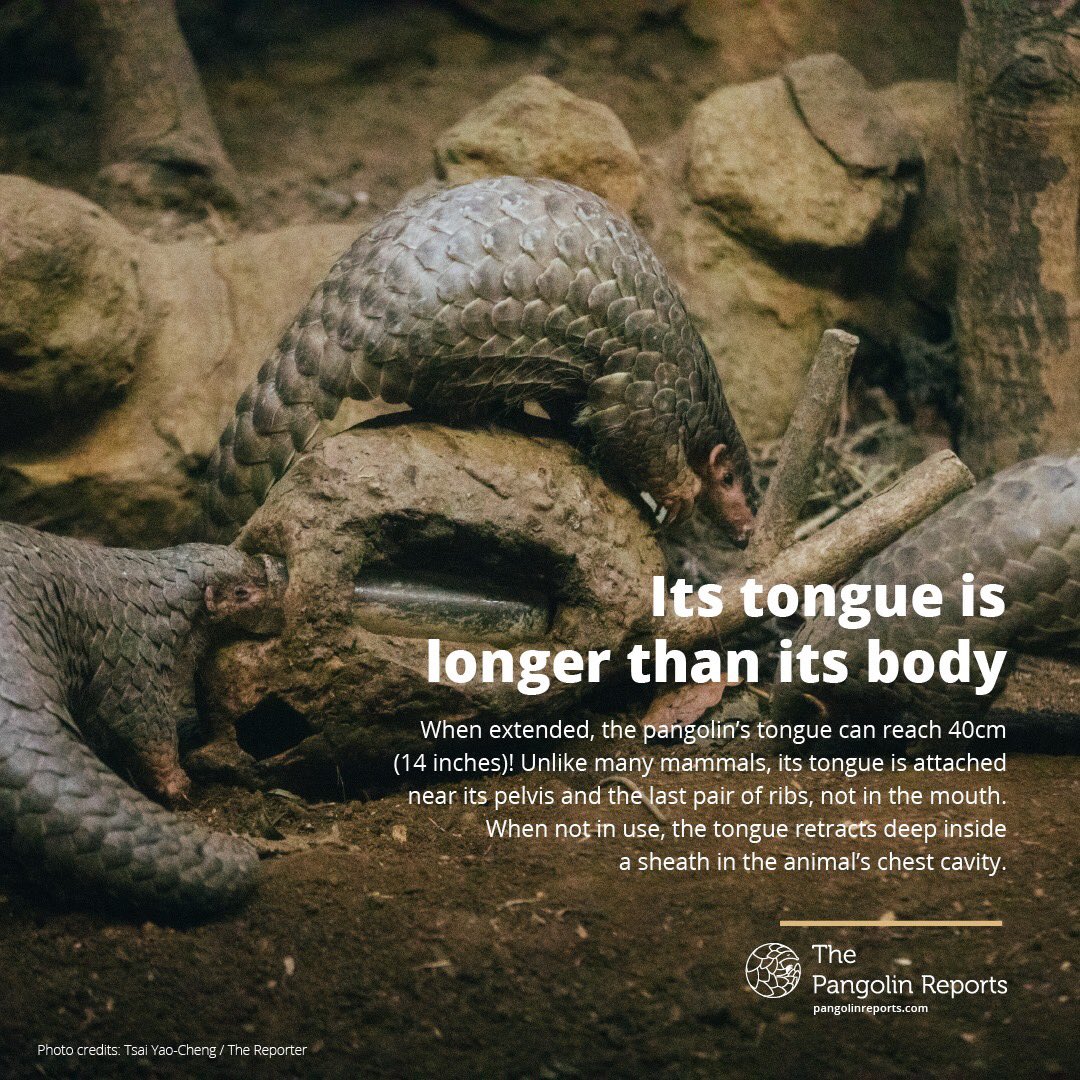

The Pangolin Reports

The world’s most trafficked mammal is a solitary anteater resembling an artichoke: the pangolin. Prized for its scales, which are particularly used in traditional Chinese medicine, this quiet animal is at the center of a sophisticated, multimillion-dollar supply chain spanning Africa and Asia and run by criminal networks.

The Global Environmental Reporting Collective, formed in early 2019, chose the pangolin trade as its first focus for in-depth investigation. More than 30 journalists from 14 newsrooms (including 10 journalists from China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan) reported in Africa and Asia, conducting dozens of interviews and even going undercover. The results are being published as The Pangolin Reports.

The journalists who participated in this project traced the illegal trade routes from roadside markets in Cameroon and elsewhere to intermediaries and traffickers in Nepal and back to China. The Pangolin Reports provide insights into how a shadow economy has thrived out of sight. Without intervention, these actions will drive the animal to extinction.

Fentanyl Trafficking

Fentanyl is quickly becoming America’s deadliest drug. In 2017, synthetic opioids, primarily fentanyl, caused more than 28,000 deaths in the United States. According to US law enforcement, China is the main supplier of the drug to the US, Mexico, and Canada. During the 2018 G20 summit, Donald Trump urged Xi Jinping to put a stop to the illegal trafficking of fentanyl from China to the US.

So how does this global fentanyl business work? Initium Media, a Hong Kong-based digital media outlet, teamed up with The New York Times to publish a compelling inside report on how the DEA cracked down on a global fentanyl ring. It shows how Chinese traffickers use fake identities and front companies to bring fentanyl to the US.

A Plague in Inner Mongolia

In November, Chinese health authorities confirmed that two villagers had contracted pneumonic plague in Inner Mongolia, an autonomous region in Northern China. The patients came from the remote region of Sunite Left Banner, close to the Mongolian border. They were transferred to Beijing for treatment. Since pneumonic plague is a serious contagious disease with high infection and mortality rates, the news caused some panic in China, where it brought back memories of the 2003 SARS outbreak.

Beijing News reporters went to Sunite Left Banner to investigate the origin of this plague outbreak. They interviewed the patients’ relatives and doctors and looked into a rat infestation plaguing the area, which is believed to be the cause of the outbreak.

Corruption in Inner Mongolia

Xing Yun is the former party secretary of Baotou city, and the former legal chief of Inner Mongolia. In August, he was accused of accepting bribes during his tenure that amounted to 449 million yuan (about $63.8 million). Xing Yun’s career unfolded in Inner Mongolia, and his downfall has shaken officialdom there. A number of officials who had held important positions in the political and legal systems of Baotou, Hohhot, and Ordos were investigated by the National Supervisory Commission and CCP’s Central Commission for Discipline Inspection.

An investigation by Caixin dug deep into Xing’s career path and his connections with senior government officials, private entrepreneurs, and local gangsters.

The Body under the Playground

The remains of Deng Shiping, who was 53 when he disappeared in 2003, were uncovered in June 2019, buried beneath a playground at a middle school in the city of Huaihua. At the time, Shiping was supervising a building project at the school. He made allegations of corruption against the project’s contractor, Du Shaoping, who happened to be the nephew of the school’s principal.

After Deng’s death, no one was arrested. His family campaigned for an investigation, but there was no result until this year. As part of a crackdown against organized crime, Deng’s family was able to appeal to a special inspection team in April. Two months later, Deng’s remains were found, and Du Shaoping was arrested.

After the case was uncovered, Caixin ran an in-depth investigation about those who protected the murderer, and why the case managed to stay covered up for 16 years. In November, 19 officials in Hunan province were fired, and 10 of them were charged with helping to cover up the murder.

Joey Qi is the editor of GIJN in Chinese. He has over seven years experience in journalism, including three years in media management. He is one of the founding members of The Initium Media, where he designed the daily news section and built the team.