7 Things I Learned Producing My First Investigative Podcast

Read this article in

中文 | العربية | বাংলা | Français | Português | Русский | Español

Like so many other journalists around the world, I was fascinated by the phenomenon that was Serial, particularly because my work at the time centered on wrongful convictions. So when the story of Anthony De Vries came across my desk in Johannesburg, where I am based, I thought this might be the story that would allow me to dig into for this format.

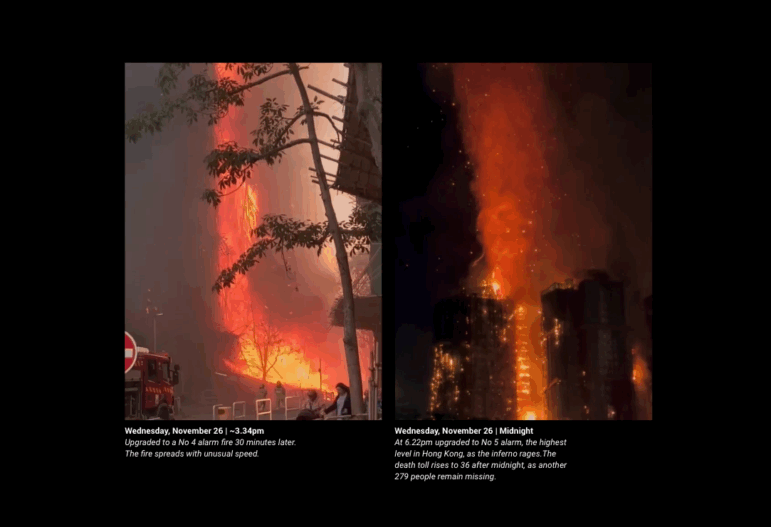

At the time I first met him, Anthony was a man in his forties who had served 17 years in jail for a crime he insisted he did not commit. It was a brutal daylight robbery in 1994, less than a month before South Africa’s first democratic election, and ended up in the slaughter of two security guards. What came out of my 18-month investigation was an eight-part series — which would be the first investigative podcast in the country when it was released in March 2017 — that went on to win a national award, and was celebrated for being “uniquely South African” while still capturing a modest international audience.

My background is in print journalism but I had done some time on a science radio show so knew a bit of the basics around radio production. But doing an investigative podcast was an entirely different beast. Here’s what I discovered while writing, producing and editing Alibi — with some advice on how you can avoid making the same mistakes.

1. It’s All in the Writing

Reporters at community radio stations often tell me that they went into radio because they didn’t want to be writers. This is a common and crazy assumption. Solid writing is what will set your audio story apart. The key is writing with extreme brevity, in a style that is appropriate for how you speak and with a structure that makes the goals of your narrator clear.

Try to capitalize on any scrap of purpose that your narrator may exhibit in order to build a sense of momentum. In Alibi, me needing to collect the court documents from Anthony’s brother in the second episode served as a powerful goal that listeners could easily grasp and understand. At first I had included scenes with the brother, but didn’t mention I was there to collect the paperwork because it took a while to understand that whenever you are on a quest during audio storytelling, you need to put that front and center, while in print you may obscure these administrative duties entirely.

You also need to offer up questions you believe the audience will be asking themselves and then tease them along for the answers. Without this back and forth, the most interesting series of events will fall flat.

In Alibi, I was trying to unravel if Anthony was in a car related to the robbery, and to what extent that car was involved in the crime. We came back to this conundrum repeatedly as each new piece of evidence was revealed.

It isn’t a coincidence that the possible wrongful conviction format — “Is he innocent or guilty?” — launched the modern day serialized podcast. It is a powerful narrative device that holds a listener’s attention.

I edited out a great number of interviews, scenes and characters during the editing process because, though I loved them, they were tangents. One which was difficult to cut was a visit to the house of Adriaan Vlok, the former minister of law and order. Vlok served the apartheid government and approved a payout to Anthony for accusations of torture by the police years before the murder and robbery case started. It was a fascinating and indulgent episode, complete with me playing with Vlok’s dog, Simba. This left the listener wondering where this was all going, as it was moving away from the central “mystery” that had been posed by the narrator. If you are used to the freedom of print, you’ll find in your shift to audio this is about to be unceremoniously restricted.

I recommend a very well spent five minutes watching Ira Glass from This American Life talk about the basics of storytelling, particularly for broadcasting. And this terrific piece in the Columbia Journalism Review about the latest Serial podcast has some important lessons for those moving from print to podcast.

2. Think in Scenes

Scene of the Crime: An early morning cash-in-transit robbery at a supermarket resulted in the murder of two security guards in 1994. Courtesy: Paul McNally

The best advice I got, which was unfortunately came far into the process of creating Alibi, was to think in scenes. Before you even write out your questions for an interview, start to imagine what scenes will anchor your story. For this, I need to credit Rob Rosenthal’s HowSound podcast. I listen to this obsessively and it taught me many things, including the appreciation that print is nimble when shifting to a different person or scene. But in radio each location or person needs to be introduced carefully, and information that isn’t captured in one of your “scenes” is likely to be lost on your listeners.

For example, I tried to save the exposition around the mechanics of the crime until we visited the strip mall where it took place. So, where bullet holes were found and getaway cars were abandoned, I built into this scene, which became the fourth episode. Originally, I had far more of this information earlier on in the series, but it was very difficult to follow without the clattering of trolleys that helped place you in the mall. Audio is incredibly powerful at creating a sense of time and space, but inefficient at conveying dense information — I realized that I needed to combine the one with the other whenever I could.

3. Your Emotions Matter

I did an embarrassing number of takes when recording voiceover while producing Alibi. That’s because it takes time to learn how your voice best expresses different emotions for an audience.

You want to sound like you are talking intimately to a handful of people rather than a few dozen. Project the emotion you want your audience to feel given the story’s development at that moment. Think of a Spielberg film. There is always a reaction shot from a character that manifests what the viewer should be feeling — you know, like in ET, the awe on the face of the little boy is in the center of the frame when we may otherwise be unsure of how to feel about the alien who has just appeared.

Moments of emotion must be curated by your voice. It’s how you hold your listener’s attention while they drive, walk around and do the washing-up.

When I started recording voiceover I had a tendency to go shrill and almost laugh when there was any emotional beat, like when I meet Anthony for the first time and don’t recognize him at first. My instinct was to play up the comedy of the situation. Not only was this dismissive of what should be a heartfelt moment, but it was confusing. Listeners thought that they missed a joke. They didn’t understand that I laugh easily and nervously at everything.

4. Keep Your Voice Recording Consistent

Keeping your recording voice consistent is more important than the actual quality. There is one episode in Alibi when I can hear my voice straining (from talking for too long) and it still bugs me when I hear it. Another was done on a different mic (not worse, just different) and it drives me nuts. I can’t stress the importance of always using the same equipment for every recording, and recording at the same time of day, with the same mic.

There’s also a side lesson here in letting go of the technical faults of your podcast. Most people won’t notice the faults at all; they haven’t listened to the tape hundreds of times like you. (Also, when when you figure out how to let go, please let me know.)

5. The First Episode is Crucial

Be honest with where your interest waned when you listened to other podcasts and what would have kept you on board. Lots of people will try out your first episode and move on. I did a full script rewrite of Alibi and re-recorded all the voiceover when I realized that the first episode was heavy on exposition and scene -setting of the crime, but didn’t end deep enough into Anthony’s character to be intriguing. Initially I only told the audience how the police who had tortured him while he was in high school were the same officers involved in the case that got him convicted at the end of episode two. In the final edit, I moved all of that into the first episode.

An example that bucked this rule was S-Town which launched all at once, with the biggest twist only occurring after two episodes. This allowed the creators to ignore this first episode rule and structure their seven episodes more like a novel.

The next plotting challenge is around cliffhangers. Constructing the ending of each episode so the listener hungers for more becomes frustrating once you are so close to your story that you are unsure as to which story beats will pull them along. These were the hardest parts to write and plot, and also where I felt like I was being disingenuous. At one point I wanted an episode to end when we discover that Anthony may have lied to us about the cause of an injury. He tells us it was a bottle, while someone else says he was hurt by a bullet. But that meant I needed to withhold an important piece of information in order to have maximum impact. But I got over it — these sorts of “gimmicks” to keep the reader hooked are the nature of the format.

6. It Doesn’t Happen If it Isn’t on Tape

You should get in the habit of putting your recorder (or even your phone) on before you get out of your car to face the world. You must always be rolling. Now, when I’m working on a story, I leave mine recording while I drive in case I want to explain my fear or apprehensions in real time. The moment when the interview is over can often be what you can use to help set up a scene or give a sense of the environment — whether it is a joke or a casual remark. You want a quiet, cozy environment whenever possible, but if there are distracting sounds that are unavoidable, you can allow them to inform your story and the depictions of your characters.

In the second episode of Alibi there was constant screeching from the wheelchair of one of my characters — Anthony’s bank robber brother — but I built that into my description of him. And once the listener knows why this is “upsetting” the interview, then they can appreciate the scene and the story even more.

7. Real Life Doesn’t Have an Ending…but People Want One Anyway

Depending on your investigation, there may be several possible endings. Because of the expectations that have been set by other podcasts, your resolution is vital. But you can “cheat” by setting different levels of outcome. Start planning early a “worst,” “medium” and “best” case scenario of endings.

Ultimately, with Alibi, while we were waiting for confirmation on its broadcast date (it was broadcast on a national radio station as well in podcast format) a number of events occurred: We got one of Anthony’s old prison guards to attest to his innocence, an old police officer said he was guilty, and Anthony got out on parole. So we had a mixed bag of an ending which meant listeners seemed unsure of what to think.

This ambiguity can generate talking points in a good way, too. A remarkable ending would have been to find and confirm the real killers and completely absolve Anthony, or prove he was guilty of his crime. While people would likely have been satisfied in a print story of having corruption exposed in the justice system (which Anthony’s case clearly did) because of the time invested and the intimacy conveyed through audio, listeners want the central character to be absolved of the crime. If he is guilty then there is a temptation to ask: What was the point?

In podcast creation you want to be recording audio as early into your investigation as possible, so when you discover your story isn’t working, you have to be willing to throw the tape out. I threw out tape for a couple of other possible wrongful convictions before landing on Anthony for Alibi, and I started recording before I knew there was a story because I wanted that first phone call, those initial reactions that you can’t recreate.

I hope all this advice helps. And please contact me with the links when you get your own investigative podcasts off the ground. I’d love to listen.

Here’s all eight episodes of Alibi, on Soundcloud or iTunes.

Paul McNally is a journalist living in Johannesburg. He is the founder of the non-profits African Investigative Radio and Citizen Justice Network and the co-creator of the social enterprise “Volume.” He is also the author of The Street: Exposing a World of Cops, Bribes and Drug Dealers and was a Knight Visiting Nieman Fellow in 2016.

Paul McNally is a journalist living in Johannesburg. He is the founder of the non-profits African Investigative Radio and Citizen Justice Network and the co-creator of the social enterprise “Volume.” He is also the author of The Street: Exposing a World of Cops, Bribes and Drug Dealers and was a Knight Visiting Nieman Fellow in 2016.