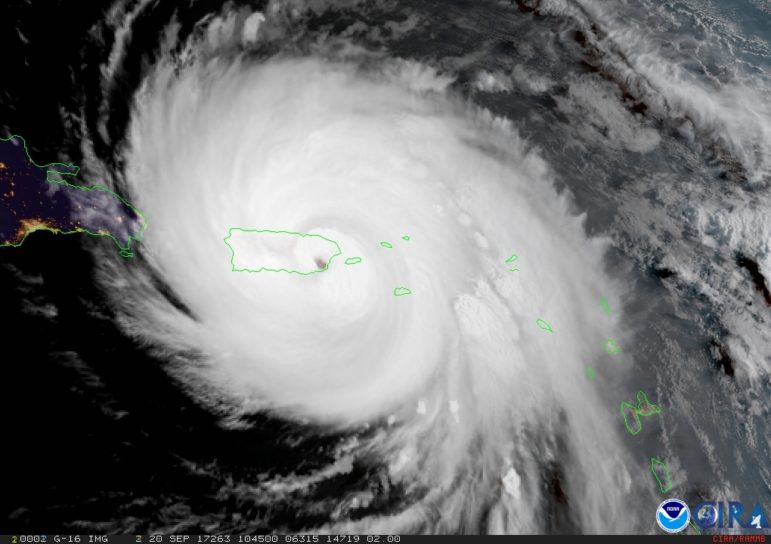

হারিকেন মারিয়ার স্যাটেলাইট ছবি: নোয়া

Puerto Rico Journalists Expose Reality of Hurricane Damage

Operational? The US military conducts an assessment of a hospital in Humacao, Puerto Rico, during Hurricane Maria relief efforts. Photo: US Marine Corps Lance Corporal Tojyea G Matally via Wikimedia Commons

On October 3, 2017, the governor of Puerto Rico announced that 63 of 69 hospitals in the US territory were “operational.” It was an unbelievable achievement just two weeks after Hurricane Maria, a Category 4 hurricane, made landfall. A local nonprofit focused on investigative journalism decided to find out if it was true.

“There were some the government called ‘operational hospitals’ but the reality was that many were not in a condition to operate nor (did they have) electric generators,” Carla Minet, journalist and executive director of the Centro de Periodismo Investigativo (CPI), told the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas.

On the same day that Puerto Rico’s governor, Ricardo Rosselló, made the announcement, CPI visited some of the hospitals and discovered they weren’t capable of admitting critical patients. For example, one hospital had a sign on the door that said they could only treat people with fevers, small abrasions and the like. Individuals with abdominal and chest pains, minors and expectant mothers couldn’t be treated there.

In an interview with CPI, a high-ranking government official later defined “operational hospitals” as “institutions that the (local) government and the US Health and Human Services Department have evaluated, and determined that their structures are ‘physically operational’ and have accepted patients.”

“It’s a case where the government was reporting data that didn’t correspond to the visits that CPI made to the hospitals,” Minet said.

But this is just one of several of CPI’s post-hurricane investigations that led to an improvement in government transparency.

A Real Catastrophe

At a time when the official death toll of victims associated with Hurricane Maria was 16, the CPI had information of many more. Sources at nine hospitals told CPI that their morgues were at capacity. Other sources said the Puerto Rico Forensic Sciences Institute was full of cadavers and that at least 25 were victims of the hurricane.

Five days after CPI’s article was published, US President Donald Trump asked Rosselló how many deaths were caused by Hurricane Maria. The governor said 16, just as his administration had been saying for the past few days.

Trump then compared Hurricane Maria’s devastation with “a real catastrophe like Katrina.”

“Sixteen people versus literally thousands,” Trump said at the October 3 joint press conference in Puerto Rico.“You should be very proud.”

Hours later, when Trump had already left the Caribbean archipelago, Rosselló announced that the death toll had increased to 34. On December 10, the official toll of hurricane-related deaths was 64.

“The death toll is something that the CPI has been questioning since the first week,” Minet said when the Knight Center interviewed her on November 8. “To this date they keep saying an amount that does not hold water.”

The flow of information is even more complicated when government agencies are not fully operational and can’t answer calls and emails due to the destruction of Puerto Rico’s communication infrastructure, according to Minet.

“The official sources are not very accessible,” Minet said. “And even the ones that are accessible frankly have been providing, in many cases, incomplete or incorrect information as has been revealed in some of our stories.”

On December 7, CPI, which is a member of GIJN, reported that 985 more people died in the 40 days after Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico than during the same period in 2016. The highest increase in deaths was seen among the elderly.

But hospitals and the official death toll aren’t the only issues in post-hurricane Puerto Rico that require a closer look by the CPI.

Puerto Rico owes at least $74 billion to public debt investors and none of them has shown willingness to put their claims on hold in light of the fact that a Moody’s report estimated Hurricane Maria caused up to $95 billion in damages.

In its first-ever collaboration with a media outlet that publishes in English, CPI joined with In These Times – a Chicago-based nonprofit magazine – reporting that 24 of 30 known financial firms competing for Puerto Rico’s debt repayments are vulture firms.

“As the name implies, these funds are like circling vultures patiently waiting to pick over the remains of a rapidly weakening company,” according to Investopedia, the financial education website. “The goal is high returns at bargain prices.”

“It seems to us that the issue of the public debt and the bankruptcy process in the courts definitely has a direct relationship with the country’s recovery,” Minet said. “In a bankrupt country that barely has money to pay its payroll, keep schools open and offer health services, definitely this issue is important because all the money that is paid to bondholders isn’t used for the recovery process.”

Going Big

Access to sensitive information regarding Puerto Rico’s debt has been possible not only because of months-long incisive reporting by CPI journalists, but also due to CPI’s partnership with the Legal Assistance Clinic of the School of Law at the Universidad Interamericana. The CPI has sued the government 10 times in access to information cases and has won every single time, according to Minet. Two of its cases related to access to information against the Government of Puerto Rico and its Financial Oversight and Management Board are still pending in court.

As newspapers and television stations in Puerto Rico lay off journalists amid the new post-hurricane economy, the CPI is looking to improve the working conditions of its current employees and to hire more investigative journalists. This is in part possible due to grants and donations that the CPI receives from sources like the City University of New York’s Ravitch Fiscal Reporting Program.

“We are looking for ways to improve the working conditions of our team and to add people to our team at a time when the country needs information with rigor and perspective about what is happening and how it affects us,” Minet said as CPI celebrated a decade of investigative journalism. “This is the time to redouble efforts to have a more solid and larger workforce.”

This post first appeared on the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas blog and is reproduced here with permission.

Omar Rodríguez Ortiz is earning his master’s degree at the Moody College of Communication School of Journalism at the University of Texas at Austin. This story was produced as part of the class Reporting Latin America.

Omar Rodríguez Ortiz is earning his master’s degree at the Moody College of Communication School of Journalism at the University of Texas at Austin. This story was produced as part of the class Reporting Latin America.