Why Open Data Isn’t Enough

Hacks and hackers meetups. Open government initiatives. Hackathons and datafests.

The media development world has discovered big data, and it is embracing it big time. Internews is sponsoring hackfests while the International Center for Journalists has turned its Knight International Journalism Fellowships into a news initiative that emphasizes “mobile services, data mining, storytelling and social media.” Donors like the Knight and Omidyar foundations are focused almost exclusively on tech fixes to what ails the media. As one prominent donor told a nonprofit newsroom executive, “We no longer fund content.”

There is a feeling afoot among some enthusiasts that digital technology can do it all, that the information and communication revolutions have so fundamentally altered how people gather and consume information that in-depth research and reporting are no longer necessary.

“Journalism itself is becoming obsolete,” wrote prominent software developer and blogger Dave Winer. “Now we can hear directly from the sources and build our own news networks.” Somehow, the belief goes, open data, citizen journalism, and crowd-sourcing will enforce a kind of high-tech accountability on the corrupt and powerful. Veteran investigative reporters, who were among the first to embrace digital tools and computer analysis, believe that couldn’t be further from the truth.

As a group, investigative reporters are hardly a bunch of technophobes. “Investigative journalism serves as the research and development department of the profession,” noted Brant Houston, whose Computer-Assisted Reporting book has helped train two generations of journalists. “They brought data analysis and visualization into journalism long before the recent open government movement, and they are the reporters who demonstrate how these new techniques can be used most effectively.”

But Houston and others are uneasy over programs that focus solely on spreadsheets and code writing at the expense of reporting. The explosion in data around the world is indeed a windfall for investigative reporters, and techniques such as crowd-sourcing can be useful. But they alone cannot do the kind of detective work that quality investigative journalism requires. The core skills of investigative reporters are similar to those of skilled prosecutors and police detectives, of field anthropologists and private investigators: the use of primary sources, the marshaling of evidence, interviewing first-hand witnesses, and following trails–trails of people, documents, and money.

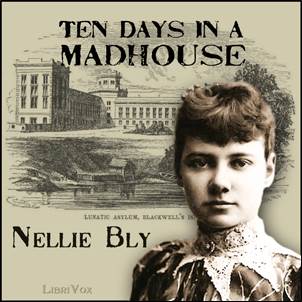

Those skills have not markedly changed since the days of the great muckrakers over a century ago. Nellie Bly, whose classic Ten Days in a Madhouse exposed medieval conditions  in a New York mental asylum in 1887, would have been helped by digital tools, but the fundamentals of her undercover investigation would not be different today. Indeed, her exposé was essentially repeated in 2009 by Ghanaian journalist Anas Aremeyaw Anas, who went undercover in an Accra mental institution and revealed outrageous conditions.

in a New York mental asylum in 1887, would have been helped by digital tools, but the fundamentals of her undercover investigation would not be different today. Indeed, her exposé was essentially repeated in 2009 by Ghanaian journalist Anas Aremeyaw Anas, who went undercover in an Accra mental institution and revealed outrageous conditions.

Consider the stories that have won Pulitzer Prizes in investigative journalism from 2010-12: an Associated Press 10-part series digging into the New York Police Department’s secret program that spied on more than 250 mosques; a year-long investigation by the Sarasota, FL, a Herald-Tribune that exposed the weakness of property insurers in the state, tracing the ownership of more than 70 companies through shell corporations; and a Philadelphia Daily News exposé of a rogue police narcotics squad, reported by doing face-to-face interviews with scared victims in poor neighborhoods.

Open data and smart tech apps can certainly help these kinds of investigations, but there is no substitute for the kind of street-level digging, personal interviews, and detective work these projects entailed.

“The increasing access to data creates, more than ever, a need to make sense of disparate pieces of information,” noted Paul Radu, the executive director of the Sarajevo-based Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. Radu has won accolades from colleagues and backing from Google for his Investigative Dashboard, a digital directory and portal to the world’s business registration databases. But he stresses that the magic bullet is combining technology with street-level investigation. “It is the mix of local and global information, the combination of local shoe-leather reporting and leaps across borders through databases, that will make the difference on the long run.”

Giannina Segnini agrees. The pioneering data journalist at La Nacion in Costa Rica has won awards for her team’s work on data-fueled stories on political corruption, and she has helped introduce its practice across Latin America. “Data journalism empowers reporters with more tools to tell better stories, but it doesn’t replace journalism’s best practices; neither does it do away with on-the-street reporting,” she cautioned. “Collecting data without conducting deep and rigorous analysis or the verification of every single record is not journalism. Tools or technical skills could never replace those essential steps from investigative journalism.”

The feeling is widely shared among professionals in media development. “The Knight Fellowships emphasize digital technology, but we feel as strongly as ever that technology has to be in the service of better journalism,” said Joyce Barnathan, president of the International Center for Journalists. “The goal is to deepen coverage, expand delivery, and engage citizens in the editorial process.”

The problem is not simply a debate of technology vs. reporting. It is a matter of priorities in a field already in dire need of greater resources. The growing attention to digital tools by donors threatens to diminish what funding exists, warn advocates of investigative journalism. Building movements for reform and social change takes more than tweets and YouTube videos, they say; an essential step is the systematic documentation of corruption, human rights abuses, injustice, and lack of accountability–work that investigators from the media and NGOs need to do. Many of the items circulated on social media during the Arab Spring, for example, had their roots in more substantive reports first revealed by al-Jazeera and other “mainstream” media.

“Technology is an extremely attractive tool for people to become engaged, to express their opinions and grievances,” argued Gordana Jankovic, director of the Media Program at the Open Society Foundations’ London office. “But it is not necessarily the best tool to encourage better understanding of the issues. The depth and context are missing, the understanding of the full picture is missing.”

Jankovic’s program has been instrumental in launching investigative journalism initiatives around the world, and she is convinced that such work remains essential. “We’re forgetting that somebody needs to develop enormous amounts of original reporting and content,” she said. “For that, you need reporters who can find the linkages and correlations between events. You need the resources to find and expose what is purposely hidden.”

David E. Kaplan is director of the Global Investigative Journalism Network secretariat. He is the former director of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and served as chief investigative correspondent for U.S. News & World Report. Excerpted and adapted from Global Investigative Journalism: Strategies for Support, Center for International Media Assistance, 2ndEdition, 2013.

David E. Kaplan is director of the Global Investigative Journalism Network secretariat. He is the former director of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and served as chief investigative correspondent for U.S. News & World Report. Excerpted and adapted from Global Investigative Journalism: Strategies for Support, Center for International Media Assistance, 2ndEdition, 2013.