Business Journalism Thrives — Even Under Repressive Regimes

Amid censorship, arrests of journalists, and a steady flow of government propaganda, one news outlet in Zimbabwe is boldly getting on with business. The Source is Zimbabwe’s first business news service and is operating across the country, breaking stories and covering that country’s struggling economy. “We are not an underground service,” says Nelson Banya, a former Reuters correspondent who is now the top editor, sitting in his brightly lit office in bustling Harare. “We are registered. We comply with the law… Our strength is that economic news is kind of viewed as less threatening.”

Amid censorship, arrests of journalists, and a steady flow of government propaganda, one news outlet in Zimbabwe is boldly getting on with business. The Source is Zimbabwe’s first business news service and is operating across the country, breaking stories and covering that country’s struggling economy. “We are not an underground service,” says Nelson Banya, a former Reuters correspondent who is now the top editor, sitting in his brightly lit office in bustling Harare. “We are registered. We comply with the law… Our strength is that economic news is kind of viewed as less threatening.”

Even as a growing number of authoritarian regimes crack down on the political press, business news is thriving. And the coverage is more vigorous than might be expected. Enterprising journalists are exposing mismanagement and unearthing shady business deals—and even at times exposing official corruption—that otherwise might never see the light of day. While other journalists face censorship, jail, or worse, business journalists are eschewing political stories to provide news and statistics on markets, business deals, and international trade.

The expansion of economic and business journalism is not a substitute for truly free and independent media. But it is a sign that—even in the most repressive environments—the demand for trustworthy information is strong and growing. And the demand comes not just from investors and citizens trying to keep track of what’s going on in these fast-changing markets, but also from governments, who themselves rely on the press for up-to-date information.

“Economic players are not going to operate in an environment where you can’t get accurate and credible information,” says Michelle Foster, an international media consultant and trainer who specializes in the business sustainability of media. “Freedom of information related to business is a critical component for businesses in making a decision to invest in a country.”

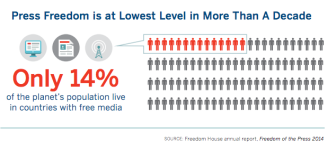

It remains to be seen whether the tolerance for business news will expand to the political realm and to increasing freedoms overall. Press freedom around the globe has fallen to its lowest level in more than a decade, Freedom House reported in its most recent annual report, Freedom of the Press 2014. The report goes on to say that the proportion of the planet’s population living in countries with free media remains stuck at 14 percent.

Countries from Asia to Africa to Eastern Europe have all seen increased demand for business and economic information that often collides with restrictive press laws and practices. The business media has attracted local as well as foreign investors, who see this area of the media market as not only meeting a strong demand, but less risky as an investment.

Countries from Asia to Africa to Eastern Europe have all seen increased demand for business and economic information that often collides with restrictive press laws and practices. The business media has attracted local as well as foreign investors, who see this area of the media market as not only meeting a strong demand, but less risky as an investment.

Governments need an accurate picture of business activity in their countries, and businesses themselves need information about market conditions and about their competitors. For media development organizations, this provides a target of opportunity. Working with journalists and news outlets that specialize in business coverage can help improve the quality of news media in general, and business coverage can also provide a means for engaging the private sector with media and media development.

All over the world, the journalism of business is booming—online business magazines alone number in the hundreds. This is true even in countries with less than free news media:

- In China, the daily business publication Caixin is doing top-notch reporting, online and in print.

- In Zimbabwe, as noted above, the business news service The Source is operating throughout the country with no interference from the government of Robert Mugabe.

- For Kenya, South Africa, and Nigeria, billionaire Michael Bloomberg has announced the launch of a $10 million program, the Bloomberg Media Initiative Africa, to strengthen economic and business coverage.

- In Russia, the daily business newspaper Vedomosti has been operating for 15 years even as general news media has struggled under government control.

- In Cambodia, a handful of business publications have sprung up.

- Latin America boasts several strong, successful business newspapers, such as Brazil’s Valor Econômico and Argentina’s Ambito Financiero.

- In Malaysia, BFM 89.9 started out as a business news radio station in 2008 but has begun to branch out into other subjects, including a recent report on the problems of indirect censorship for news media.

Within their focus on business, economics, and finance, media outlets such as these also engage in investigative journalism that can uncover corruption.

Asking Tough Questions in China

“China doesn’t want the spread of fake pharmaceuticals,” says Joyce Barnathan, president of International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) and a former correspondent for BusinessWeek based in Hong Kong. “Areas of investigative journalism are thriving.”

Since 2007 the ICFJ has operated a highly popular global master’s degree program in business journalism at Tsinghua University in Beijing. The program is run in partnership with Bloomberg and has received funding from Bank of America. Bloomberg journalists teach in the program, and there are Bloomberg business computer terminals available to the students, which gives them business data in real time. Barnathan attributes the interest of these U.S. financial institutions in the program to their realization that “these are the emerging business leaders” in China.

“The business press has improved markedly in the last five years,” Barnathan says. “Business reporters ask tough questions now.”

Jane Sasseen, a longtime journalist and now executive director of the McGraw Center for Business Journalism at City University of New York’s Graduate School of Journalism, taught financial journalism at Tsinghua in the fall of 2013. Even though political reporting is strictly controlled, the Chinese authorities “understand they need more economically literate reporters who can write about the economy… global trade and how the global economy works,” Sasseen said in an interview. “There’s a lot more freedom and flexibility around that.”

She found the students enthusiastic about the subject. “They’re hungry. They’re dying to understand the way the world works.”

Sasseen taught an introductory unit on the stock market, giving each of her students an imaginary $1,000 to buy a stock portfolio. But she had to begin by explaining what a stock market is and where you get the information about the stock as well as other basics of economics: “How do central banks work? Why is monetary policy important? How to read a financial statement? How do markets work?”

The students learned that information about Chinese companies—even those controlled by the government—is available online if the companies file with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, even if that data is not available in China.

Sasseen says she has seen accurate reporting in the Chinese business press but somewhat less deep coverage than one would see in U.S. business publications. “Stories tended to be weaker on analysis, on explaining the difficulties a particular company’s strategy or a proposal might face. That’s one of the most important things we focused on in teaching all our courses.” On the other hand, she says, she has noticed an increase in investigative reporting about the environment and services.

A Chinese journalist who requested anonymity concurred, saying that business journalism in China has become more professional and that there has been greater interest in coverage of environmental issues lately.

Tsinghua’s graduates are in high demand by employers, Barnathan says, calling them “the hottest hires in Chinese media.” The students receive hands on and practical instruction in English, which is attractive to Chinese media organizations as they go ever more global in their ambitions.

One Chinese business journalist, Hu Shuli, has made her mark internationally. In 2011, Time magazine named her one of the 100 most influential people in the world, calling her “a paragon of reporting brilliance in China.”

In 1998, Hu founded the business magazine Caijing (whose name translates as “Money and Economy”). A decade later she and many members of the staff left Caijing following a dispute with the publisher. The ostensible reason had something to do with the shareholding structure of the ownership, but she had been overseeing hard-hitting investigative journalism and exposing corruption.

She and her colleagues launched Caixin (“Money News”) in 2009, and it has been producing well-respected business journalism ever since. Caixin’s coverage doesn’t shy away from touchy subjects. For example, an article in June 2014 detailed an investigation into possible racketeering by executives of the state-owned CCTV and raised questions about the lack of a firewall between CCTV’s advertising and editorial operations.

Defying the Odds in Zimbabwe

In Zimbabwe, where the government of Robert Mugabe has closed the media space, The Source is thriving. The business news service was launched in October 2013 with support from the Thomson Reuters Foundation and the Dutch Foreign Ministry via the European Journalism Centre (EJC).

In Zimbabwe, where the government of Robert Mugabe has closed the media space, The Source is thriving. The business news service was launched in October 2013 with support from the Thomson Reuters Foundation and the Dutch Foreign Ministry via the European Journalism Centre (EJC).

“It borrows from the Chinese model. You can see real progress in China,” says Josh LaPorte, the EJC’s country project manager for Zimmbabwe, who was key to getting the project off the ground. “It’s a way to spread journalism’s wings.”

The Source’s stringers around the country learn their craft on the job and write stories outside of the area of business. “It does raise the bar of journalism in general,” LaPorte says.

The Source is set up with two seasoned media hands in the Harare bureau and a dozen stringers spread out over the rest of the country to cover local economic news. Mainstream media are clients, and they judge their success by how many of their stories get picked up by other media. During an interview in Harare, Banya flipped through a binder of stories that were broken by The Source and then carried or followed up by local newspapers. He pointed proudly to a single page in the Zimbabwe Mail where two prominent stories were attributed to The Source.

“We’ve been quite happy because we’ve never gotten so much pick up in the local press.” Banya says. “We have a stringer in virtually every town in the country. Zimbabwe hasn’t seen anything like it. There has been very little coverage of the rest of the country, outside the capital. Our view is that a lot of big things start as a series of small things.”

“Zimbabwe is a country that needs (foreign direct investment). Potential investors are looking for trustworthy information.” Banya says. “The economy is now more important than politics. The players in the local economy are starved of economic data.”

“There is also a lot of confusion about policies. We try to keep people informed and on track about changing policies, present as clear a picture as we can of the investment climate.”

Banya says that so far the government has not placed restrictions on his team’s reporting or censored any of The Source’s reports.” The biggest obstacle has been starting a new service, getting our brand recognized,” he says. “We have a fairly litigious government, but we have had no lawsuits.”

He is not sanguine about the prospects of continued freedom, however. “Economic conditions are worsening. If things go badly, the government can lash out… For now, we enjoy peace, but I wouldn’t bet on that continuing forever.” LaPorte says The Source is supported through 2015 under a five-year project of the Dutch Foreign Ministry via a consortium of Dutch NGOs called Press Freedom 2.0. The consortium has about 20 million euros in funding, and the portion for Zimbabwe is about 2.2 million, about half of which is for The Source.

Business journalism presents an opportunity, LaPorte says, because “there is such a gap in Zimbabwe.” The journalism schools “were horrible as a recruiting ground as they had been devastated,” he says. Under Mugabe, attacks on independent media had made it “so nobody wanted to be a journalist anymore.” Journalism schools were mainly churning out people who would become government spokesmen, so they recruited in business schools and taught business students how to write.

The Source is registered as a trust, and to sustain itself in the future it will likely have to rely on the use of public money—what LaPorte called “public venture capital”—to eventually create a for-profit enterprise.

Working in Other Difficult Media Environments

Other examples of business news organizations operating in difficult media environments can be found in a variety of places, including Russia and Cambodia. In its chapter on Russia, Freedom House’s Freedom of the Press 2014 says:

Meaningful political debate is mostly limited to weekly magazines, news websites, some radio programs, and a handful of newspapers such as Novaya Gazeta or Vedomosti, all of which are aimed at urban, educated, and relatively well-off Russians. Although these independent outlets are tolerated to some extent, the main national news agenda is firmly controlled by the Kremlin.

The daily business newspaper Vedomosti has been around since 1999. It was founded with the support of the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times and is now owned by Sanoma Independent media, billed as the largest publisher in Russia. According to its website, Vedomosti sees its mission as informing “readers on a daily basis about the most important economic, political, financial and corporate events.”

The daily business newspaper Vedomosti has been around since 1999. It was founded with the support of the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times and is now owned by Sanoma Independent media, billed as the largest publisher in Russia. According to its website, Vedomosti sees its mission as informing “readers on a daily basis about the most important economic, political, financial and corporate events.”

In Cambodia there are a variety of publications covering business news, according to media consultant Michelle Foster, who has worked there. Some of the strongest business reporting is in Chinese, Foster says, adding “and the major investor in Cambodia is China.”

It’s a measure of the importance of media to functioning markets and the private, commercial sector that former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg would invest $10 million to improve news media in Africa. The press release announcing the initiative in February 2014 says:

Timely and accurate reporting of business and financial matters play a critical role in advancing efficient markets and is a key driver in supporting economic and social growth. Strengthening business and economic news coverage, expanding training programs for journalists and providing greater access to reliable data about Africa are frequently cited as important enablers to the continent’s continued development.

Bloomberg’s initiative includes partnerships with universities in Kenya, South Africa, and Nigeria and will focus its energies on mid-career fellowships for journalists, sharing journalistic best practice at forums, and offering cross-disciplinary education.

“Reliable data and financial analysis bring transparency to markets and promote sound economic development—and they can help keep Africa growing and creating opportunity,” Bloomberg said in the initiative’s announcement.

Bloomberg’s involvement in business journalism education at Tsinghua University in China and his newer initiative in Africa serve as clear examples of what the private sector can do to help develop sustainable news media. The media development community would do well to reach out to other businesses and engage them in the effort to improve and support media around the world.

This article originally appeared as a briefing paper for the Center for International Media Assistance at the National Endowment for Democracy and is reprinted here with permission. CIMA Senior Director Mark Nelson contributed to this report from Harare, Zimbabwe.

Don Podesta is manager and editor at CIMA. At the Washington Post he served as an assistant managing editor, deputy foreign editor, and South America correspondent, covering Peru’s war against the Shining Path guerrilla movement and drug violence in Colombia. Before that, he worked as an editor or reporter for the Washington Star, Minneapolis Star, Miami Herald, and Arizona Republic.

Don Podesta is manager and editor at CIMA. At the Washington Post he served as an assistant managing editor, deputy foreign editor, and South America correspondent, covering Peru’s war against the Shining Path guerrilla movement and drug violence in Colombia. Before that, he worked as an editor or reporter for the Washington Star, Minneapolis Star, Miami Herald, and Arizona Republic.