Imagine: GIJN

Sanctions Evasion, Army Executions, and a Royal ‘Flying Palace’: 2025’s Best Investigative Stories from Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and the Caucasus

Read this article in

In 2025, authoritarian rulers and oligarchs across this region intensified their struggle not only for power and wealth but also for citizens’ minds in the digital space, forcing journalists to combine old and new investigative methods to expose violations in the virtual world.

Ziarul de Gardă journalist Natalia Zaharescu continued her award-winning undercover work investigating Russian influence in her country in her new investigation, The Kremlin’s Digital Army in Moldova. Along with hundreds of other “communication activists,” Zaharescu learned online from a team of Russian-speaking curators how to deceive Telegram and TikTok algorithms, sow fear and doubt among Moldovan voters, and promote anti-European texts that coincided with Russian propaganda narratives.

Journalism in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and the Caucasus not only informs the public and exposes misinformation; it is often a vital tool for holding authorities accountable, exposing corruption, and documenting injustice.

The Baltic countries consistently rank highly in the RSF’s World Press Freedom Index, followed by Armenia, Moldova, and, somewhat behind, Ukraine. (Read more about the situation in Ukraine in the Ukrainian editor’s review.)

According to Edik Baghdasaryan, the founder of the Armenian investigative outlet Hetq, their reports have led to the return of stolen funds into the budget, the initiation of criminal proceedings, the resignation of politicians, and the dismissal of officials.

However, in many post-Soviet countries, journalists face physical threats, arrests, surveillance, and financial pressure while doing their job.

Azerbaijan, Belarus, Russia, and Turkmenistan were among the 15 countries with the lowest scores in the World Press Freedom Index 2025.

Having destroyed independent media in the country, Russia continued to persecute journalists even in exile.

On March 7, 2025, a jury at the London Criminal Court found a group of Bulgarian citizens guilty of spying for Russia. They had been recruited by Russian special services to kidnap and possibly murder Russian investigators Christo Grozev and Roman Dobrokhotov from The Insider. Using recordings from the perpetrators’ phones and police surveillance video footage, the journalists showed how they managed to uncover the surveillance targeting themselves.

Likewise in March, exiled IStories founder Roman Anin and journalist Ekaterina Fomina were sentenced in absentia by a Russian court to more than eight years in prison, allegedly for spreading “fake news” about the army — which were, in fact, journalistic investigations into potential Russian war crimes in Ukraine. In December, Anin was also stripped of his Russian citizenship.

Russia has also become one of the world leaders in terms of the number of foreign journalists imprisoned. According to the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine, at least 30 Ukrainian journalists are currently being held in Russian prisons. Many of them, like thousands of other Ukrainian civilians, are being held “incommunicado” — they are not even allowed to see a lawyer, and no one knows where they are or whether they are alive or dead.

Last year, the world was shocked by the story of one of these ghost prisoners, 27-year-old Ukrainian journalist Viktoriia Roshchina. She had wanted to investigate the disappearances of people in the occupied territories, but she herself was taken prisoner by Russia. A year later, her relatives received news of Roshchina’s death, and a few months later, Russia reportedly returned her body missing some internal organs and with signs of torture.

Journalists from six countries, including the reporters of Russian IStories and Ukrainian Ukrainskaya Pravda, worked together with the French organization Forbidden Stories in the framework of Viktoriia Project to find out how she died and continue her investigation into Ukrainian prisoners in Russian jails.

Arrests and imprisonment also threaten local journalists in Central Asia and the Caucasus.

The Azerbaijani Court of Appeals upheld lengthy prison sentences (seven to nine years) for seven journalists from Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) and the investigative news outlet Abzas Media. They had been arrested in 2024, allegedly on charges of smuggling currency, but in reality for receiving grants from respected international donors.

Georgia, despite mass protests and civil society resistance, is gradually adopting the anti-democratic methods of its neighbors. In the RSF’s 2025 press freedom ranking, the country fell to 114th place from 103rd the previous year. Due to repressive laws passed by the ruling party, in particular a “foreign agents” law modeled on similar Russian legislation, several Georgian TV channels have ceased broadcasting, dozens of online media outlets have been shut down, and dozens of other independent media outlets continue to operate in survival mode, according to SOVA.

In Kyrgyzstan, which just a few years ago seemed like an oasis of independent journalism in Central Asia, there’s also been a legislative push to limit the activities of independent media. At the same time, legal pressure has increased: in May, eight employees of the investigative media outlet Kloop were detained; in September, two of the arrested journalists were sentenced to five years in prison, and in October, a court declared the publications of Kloop and Temirov Live, as well as the activities of Temirov Live founder Bolot Temirov and Kloop founder Rinat Tuhvatshin, to be “extremist.” Both investigative outlets now operate in exile, serving as prime examples of the suppression of press freedom in Kyrgyzstan, which has been ongoing since 2022, according to OCCRP.

Despite these obstacles, journalists from the region continue their investigative work, countering threats and financial pressure with their unprecedented courage, regional and international partnerships, cooperation with civil society institutions, increasingly sophisticated use of digital tools for open source research, and the use of programming and teamwork to analyze large datasets.

Trade with Russia, Avoiding Sanctions

Several cross-border journalist teams examined various aspects of this topic, demonstrating the influence and effectiveness of international cooperation in tracing financial flows and supply chains.

How Rapeseed from Ukraine’s Occupied Territories Ends up in Europe

Schemes, the investigative program of the Ukrainian service of RFE/RL, together with the Belarusian Investigative Center and Lithuania’s 15min, analyzed import and export documentation, tracked possible links between suppliers and Russia, and concluded that the EU buys oil from rapeseed imported from the occupied part of Ukraine and processed in Belarus. (Read more about the illegal export of Ukrainian grain in our review of the best investigations from Ukraine.)

Importing Sanctioned Goods Into Russia

The Belarusian Investigative Center, the Lithuanian investigative center Siena, and the Russian media outlet Chronicles.Media, conducted this journalistic investigation with the support of the activist group Cyber Partisans. By analyzing social media advertisements, experimental clothing purchasing, and tracking supply chains, they uncovered how global luxury brands can still reach Russian fashionistas, bypassing sanctions, with reduced duties and without the copyright holder’s permission, via Belarus, Hong Kong, Lithuania, the UAE, Serbia, Turkey, and Uzbekistan.

Similarly, Sistema and Current Time (RFE/RL’s Russian service) analyzed who was importing luxury cars into Russia and how they did it. In response to a journalists’ request, global automotive giants launched internal investigations.

Temirov Live, OCCRP, IStories, and Forbidden Stories reported on how Kyrgyzstan became a transit point for schemes to export sanctioned cars to Russia.

And in an examination of trade circumventing sanctions, Georgia’s iFact listed illegal schemes used to transport trucks and trailers to Russia via Georgia and neighboring countries.

From Enamel Pots to Kamikaze Drones

The Belarusian Investigative Center (BIC) team reported on how a well-known Belorussian cookware factory conducts a hidden arms business, with “pots and pans on display, drones for war under the counter.” Surprised to find quadcopters even on the company’s website — hawked alongside mundane household items — journalists began to study customs documents, papers provided by a source in the logistics sector, and financial reports of Russia’s largest drone manufacturer. After analyzing the ownership structures and suppliers, journalists concluded that the cookware factory’s owner or a close relative had apparently received approximately US$1 billion from Russian intelligence.

That report was the second part of an investigative series into how Belarusian companies circumvent restrictions and sell various types of Chinese drones to Russia, which the Russian Army uses to terrorize Ukrainian civilians. The BIC collaborated with Latvian TV3, and had support from OCCRP and Cyber Partisans.

International Fraudsters from Georgia

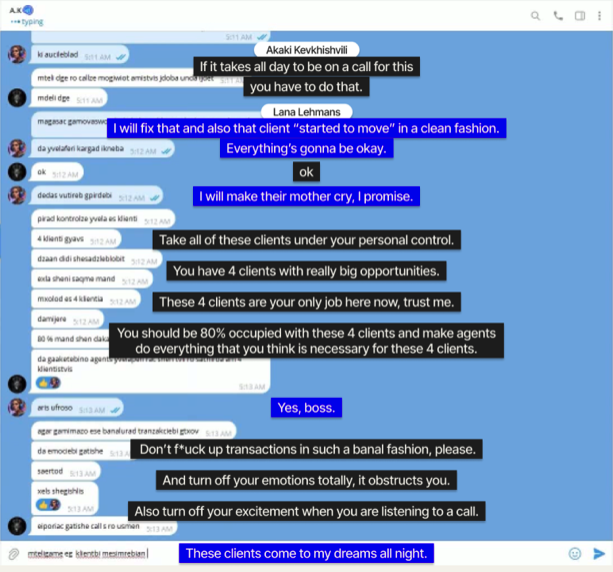

This investigation is a part of a joint cross-border Scam Empire project, where journalists from 30 media sites, including OCCRP, Georgia’s iFact, Studio Monitori, and GMC, described the workflow of two call centers operating in Tbilisi, employing 85 operators who defrauded around 6,100 citizens of Europe, the US, and Canada of more than $35 million between 2022 and 2025.

According to the investigation, all center operators used fake IDs, forged documents, and misleading advertisements; “investors” were systematically prevented from withdrawing their invested funds; and almost all of the investment “products” offered were unlicensed.

The journalists’ team managed to uncover the scheme and the identities of the potential perpetrators by analyzing surveillance camera footage, monitor screenshots with invoices, salaries, and multiple other data points, and call audio recordings from the scammers’ offices provided to Sweden SVT by an anonymous source.

The stolen funds allowed young Georgian fraudsters to live and travel like kings and queens, and they couldn’t resist bragging about it online. This behavior helped OCCRP and their Georgian partners identify some of the scammers by comparing topics from work chats (mentions of trips, cars, and relatives) with their social media posts.

The scammers also made another mistake: the photo booth they rented for their corporate party published all photos online. Due to those photos, journalists got portraits and could identify many of the scammers.

Telegram’s Links to Russian Intelligence Agencies

To find out who manages the servers of one of the world’s most popular messaging apps and who has access to its traffic, IStories conducted a digital investigation, analyzed documents from the US court registry, and concluded that Telegram’s technical infrastructure is controlled by a network engineer whose companies have collaborated with the Russian defense sector, security services, and other secret agencies. According to the reporters, those responsible for Telegram’s infrastructure are the same people who maintain the secret complexes of the Russian special services used to spy on citizens.

Telegram CEO Pavel Durov did not respond to questions about this engineer’s access to the platform’s infrastructure when questioned by IStories.

Inside Russia’s Teen Mephedrone Crisis

BBC Russian Service journalist Anastasia Platonova spent five years tracking the supply chain of one of Russia’s most popular drugs, mephedrone. The author of the investigative documentary (also available in Russian) recounted how she analyzed drug blogs on Telegram, studied hundreds of thousands of customer reviews on websites selling drugs on the darknet. She also communicated with addicted teenagers and a “chemist” who synthesizes mephedrone in an underground laboratory, contacted suppliers from China under the guise of being an anxious buyer, tracked the import route to Russia via Kazakhstan, and found wholesale warehouses through which deliveries were made using satellite images and maps.

Royal Luxury at the Expense of Turkmenistan’s Official Budget

Turkmen.news and gundogar.media, in collaboration with OCCRP, reported on how the family ruling in Turkmenistan for two generations, recently added a fifth aircraft to its VIP fleet. The journalists analyzed photos from social media, flight information, and other open source data and concluded that a US company, commissioned by the Turkmen state airline had converted a 118-seat passenger airliner into a private “flying palace” for the family, replete with gold-plated plumbing and exclusive carpets. This lavish expense using government funds took place in a country where even a standard international airfare is beyond the means of most citizens.

False Identities of a Jailed Moldovan Oligarch

The Moldovan investigative newsroom CU SENS, in collaboration with OCCRP and journalists from six countries, tracked one of Moldova’s richest men who has been hiding from justice using several aliases for the past six years. Following these identities in Romania, Ukraine, Bulgaria, Russia, Iraq, and Vanuatu, the team visited addresses where he was allegedly registered and even a cemetery where a man whose name, surname, and place of birth were stolen by the fugitive oligarch is buried. The former politician was reportedly detained along with a party colleague in Greece in July 2025 at Athens International Airport as he was about to use one of his fake passports to travel to Dubai. During a raid on the seaside villa where the fugitive had been living for several months, Greek police seized more than €155,000 in cash, as well as expensive watches, phones, and 17 fake passports and identity cards.

Another excellent example of cross-border cooperation in the region was the story of the new life of a fugitive Ukrainian oligarch. OCCRP, working on together with Greece’s Inside Story, the Belarusian Investigative Center, Ukraine’s NGL.media, and Serbia’s KRIK, revealed how the tycoon, wanted after his involvement in a fatal car crash, obtained both a Greek “golden visa” and Serbian citizenship, conducted business in five countries, and had companies linked to him trading in weapons. For the investigation, the team analyzed leaked documents, interviewed sources, checked border service data, and sent information requests to government agencies in various countries.

How Executions Are Carried Out in the Russian Army

The Russian media outlet in exile Verstka has compiled a database of more than 100 commanders and military personnel who, according to the investigation, have killed their fellow soldiers as punishment, for intimidation, or simply to settle personal scores. After interviewing military personnel and their relatives, as well as studying a large number of complaints about such crimes filed with the Chief Military Prosecutor’s Office, the journalists detailed how these killings are carried out as executions, fatal torture, or deadly orders, such as sending soldiers on a “meat assault” without weapons, support, or equipment. According to the story, torture is becoming increasingly brutal, and executions are growing more widespread among the Russian Army’s ranks.

‘Fathers and Grandfathers’ in Russian Government

This deep, large-scale, and systematic investigation could be called an encyclopedia of nepotism in the Russian government.

Twenty journalists and designers from exiled investigative media site Proekt.Media spent 18 months studying the biographies of approximately 10,000 Russian officials and their relatives, compiling dossiers on those civil servants who either placed their spouses, children, grandsons, and granddaughters in government service or helped them start businesses that prospered thanks to government contracts. According to the exposé, 76% of Russia’s top officials are involved in nepotism. Based on the analysis, Proekt compiled a list of more than 1,000 names and systematized a database of Putin’s nomenklatura across the various branches of government.

Bonus story: System Failure in European Medicine

This cross-border investigation involving Re:Baltica, OCCRP, and other media outlets reveals that more than 100 doctors who have lost their medical licenses in one European country due to serious wrongdoings continue to work in another. To identify specific cases and uncover accountability gaps, journalists collected information from 45 countries and developed their own database of doctors with valid certificates and those whose certificates had been revoked. The team obtained data from public registries, sent hundreds of FOI requests, and searched in court records, local media reports, and other sources. The dataset is still incomplete because some countries refused to disclose information, even though this is necessary to protect patients’ rights.

Olga Simanovych, a native of Ukraine, has more than 13 years of television experience as a journalist, screenwriter, and managing editor. Seven of those years were spent as a TV news reporter for the Vikna-Novyny program on STB, where she specialized in politics, environment, human rights ,and medicine. From 2011 to 2016, she was a media trainer with different nonprofit organizations and participated in SCOOP‘s international investigations. A graduate of Taras Shevchenko National University, Ukraine, she is bilingual in Ukrainian and Russian, and fluent in English and Greek.

Olga Simanovych, a native of Ukraine, has more than 13 years of television experience as a journalist, screenwriter, and managing editor. Seven of those years were spent as a TV news reporter for the Vikna-Novyny program on STB, where she specialized in politics, environment, human rights ,and medicine. From 2011 to 2016, she was a media trainer with different nonprofit organizations and participated in SCOOP‘s international investigations. A graduate of Taras Shevchenko National University, Ukraine, she is bilingual in Ukrainian and Russian, and fluent in English and Greek.