Crowdsourcing in investigative journalism

13. oktober 2010 17:06

[This is the first of a new GIJN feature on investigative techniques.]

By Nils Mulvad

Crowdsourcing is normally regarded as defined in 2006. Jeff Howe is often credited with the term “crowdsourcing” in a Wired article of June 2006, entitled “The Rise of Crowd sourcing”.

Wikipedia defines it as: “Crowdsourcing is a neologistic compound of Crowd and Outsourcing for the act of taking tasks traditionally performed by an employee or contractor, and outsourcing them to a group of people or community, through an “open call” to a large group of people (a crowd) asking for contributions.”

Poynter has defined crowdsourcing in journalism as: “Crowdsourcing is taking a task traditionally accomplished by a professional journalist and includes outsourcing to a large group through an open call.

Members of the public might be asked to gather information, use their expertise to examine documents, or participate in other ways.”The main task is to get non-specialists to participate in the journalistic process. This can be done to various degrees. You will have a journalist as the project leader and coordinator and then the crowd to perform tasks. There have been several projects done according to this concept, some successful, others not so successful.

Since 2006, we have also seen a big growth in blogging and the use of Facebook to interact more with the readers, normally to have a discussion on methods, and to get comments and tips. It can be difficult to draw a clear line from this broader interaction with the crowd over to traditional crowdsourcing. The rise of this interaction can be seen as building the basic background for later asking the crowd for specific help.

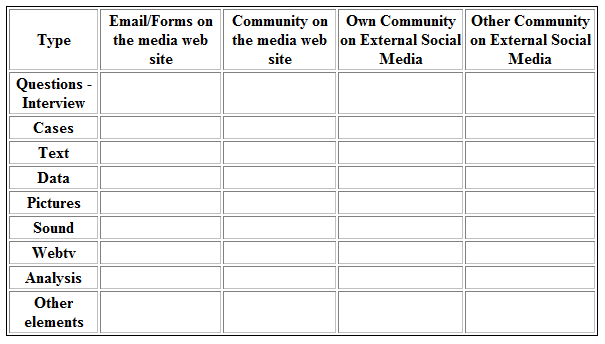

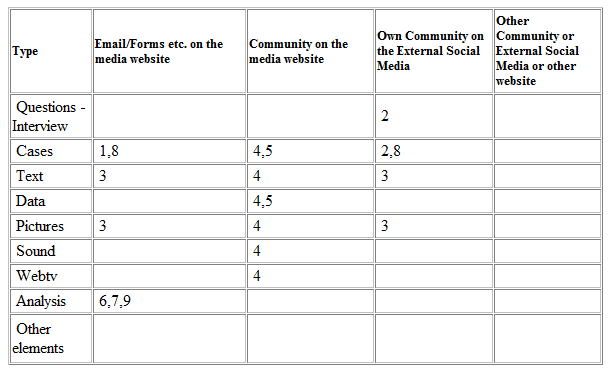

Different kinds of crowdsourcing – the matrix

In practice we can divide crowdsourcing according to the part of the journalistic process where the crowd is helping, and which tools are used to organize this help. This gives us this matrix:

You can imagine the crowd contributing with other parts of the journalistic process such as editing, but that will be rare now, I think. We might add other parts of the journalistic process later to this matrix.It should then be possible to place different crowdsourcing projects in the different cells in the matrix, and use it for the purpose of analyzing how to get success out of these projects.

Still it’s also obvious we’re looking at this whole process from the angle of the journalist. How can he/she use the crowd to get better stories? In a long perspective this angle might be too narrow, because also the journalist is only one party in the process of uncovering a specific story, where you’ll see a lot of other actors, so it might be better to look at the process as a whole. But for now we will focus only on the crowdsourcing – looking at it from the journalist point of view.You might also divide the crowdsourcing projects according to other categories. This could, for instance, be timing:

- The crowd gather information while things are happening

- The crowd send you information after the things have occurred

You might also divide crowdsourcing projects according to the kind of media:

- Big, well-known media with a long tradition of crowdsourcing

- Well-known media experimenting with crowdsourcing

- Small media – not so known – with a long tradition of crowdsourcing

- New, small media starting their first project.

You might also divide according to the kind of story:

- Stories with a broad appeal to the crowd where it’s obvious that the crowd has the potential to help with a lot of cases (parking fines, policy response time, doctors response time, disasters).

- Stories where you identify an existing community and get it to help. It can be a rather specific area, but the good thing for you is that others already have gathered the crowd.

- Stories with no community and no potential knowledge in the crowd (tax paying by multinational companies, defense contracts).

- Stories where you have the documentation, but need help for analysis (it could also be defense contracts, state budget, and calendar of a prime minister).

And you might divide according to which tools you use to raise involvement and get the crowd to help:

- It’s using more campaign-like tools like planning stories from a rap-contest to get young people into the community. And there can be a lot of other tools here.

These four other ways to categorize crowdsourcing projects might also be useful for analysis. But in this handout I’ll later continue with the matrix, described above.

Future of crowdsourcing

In his book “Here Comes Everybody” Clay Shirky uses the phrase “the Internet runs on love” to describe the nature of crowdsourcing and collaborations. He points to four key steps.

The first is sharing, a sort of “me-first collaboration” in which the social effects are aggregated after the fact. People share links, tags, pictures, and eventually come together around a type.

The second is conversation, that is, the synchronization of people with each other and the coming together to learn more about something and to get better at it. It is also here we normally see the first formation of a community.

The third is collaboration, in which a group forms under the purpose of some common effort. It requires a division of labor, and teamwork. It can often be characterized by people wanting to fix a failure, and is motivated by increasing accessibility. It is also here we see the development of the community, and normally just a few doing the main part of the work.

The fourth, and final step, is collective action, which Shirky says is “mainly still in the future.” The key point about collective action is that the fate of the group as a whole becomes important. He also notes that we are experiencing an era where people like to produce and share just as much, if not more, than they like to consume. Since technology has made the producing and sharing possible, he argues that we will see a new era of participation that will lead to major change.

All this will also very much change the role of the investigative journalist too. In many ways this will question the neutral role of the journalist. If we work with a community to gather information, where it develops the idea of a collective action, we will face a problem in the traditional ethics of journalism. I don’t have the right solution to this, but I can see that we will not have such a community to work with the main purpose of helping journalists doing their job. Their main purpose will be the development of the community and where the journalist and the investigative project will just be regarded as one contribution.

The copyright rules under creative commons will also be part of this development. More and more journalists will publish their data, stories or pictures under this regulation. It will then be easy for others to reuse/remix. Farmsubsidy.org do this with their data, where users can make their own group of data and then republish on their own website. The Guardian also publishes data like that.

Examples

Numbers refer to the stories below.

1. The Crime, Berlingske Tidende, Denmark, 2008. An investigative project about how the police, after major restructuring, didn’t have time to come when called. The major case was a murder where, although a man called several times, the police refused to attend and subsequently, even failed to recognize the death as murder.Crowdsourcing was used to gather more cases after the release of the project. All the cases kept the focus on the main question, and helped prove the problem. Readers filled out a form or sent email with their story. Some stories were investigated by the journalists, others just published on a Google-map.

2. In the hands of the doctor, Berlingske Tidende, Denmark, 2009. An investigative project about how doctors don’t listen enough to their patients. The big case was a baby dying after swallowing a battery, but the doctors wouldn’t take an x-ray before.Crowdsourcing was used to get ideas, comments and cases by a specific group on Facebook. It was a separate community keeping the focus on the project.

3. Tehran Bureau, US, 2009. After the election in Iran 2009, traditional journalists were forced to leave or report under censorship. The most valuable source then was the Tehran Bureau gathering reports from Skype, mails, telephone and Twitter and sending them out on Twitter.Crowdsourcing was used as the basis for this project, simply to get the unreported stories out from Iran. It used several methods to get the information in text and pictures and still protect the sources.

4. Operation Pedro Pan, The Miami Herald, US, 2009. Operation Pedro Pan was a website on the media-website of The Miami Herald, a community for the 14,048 children sent to the US by wealthy Cubans after the revolution in 1959.It’s a Facebook-like community with some basic information about everyone and where you can add more information and find old friends. Nearly ten percent of the children have joined today.

5. Tsunami-disaster in Asia, VG, Norway, 2005. The Norwegian paper, VG, collected a list of missing Norwegians in one day by asking the crowd, publishing and asking for more help from others. Their list was 79 percent correct, while the Foreign Ministry was five days to make a list, and it was only 6 percent correct.It was an open community on the media website, collecting and refining a list of names.

6. Analyzing MP’s spending, The Guardian, United Kingdom, 2010. The Telegraph started the story on the spending by the Members of the UK Parliament. But it was the Guardian which made a breakthrough by twice publishing a huge list of documents on spending and asking the public for help to analyze it.Good example of asking the public for help doing the analysis.

7. Analyzing the state budget, Berlingske, Denmark, 2010. The paper asked their readers to help analyzing the new proposal for the state budget. They got very few responses and mostly more comments, but nothing useful for a story.Example of where it’s difficult to use crowd sourcing.

8. Dangerous production, Åbenhedstinget, Denmark, 2008. The small website asked the readers to contribute to finding dangerous production and got rather good tips and put them on a map. It was also supported after the website was quoted by the Danish Broadcast Corporation where also a lot of cases were gathered.

9. The lost JFK-files, Dallas Morning News, US, 2008. The paper asked the readers to help analyzing a trunk of files of the assassination of JFK.

Getting started with crowdsourcing: If you have a small media or this is the first project in crowdsourcing these hints can be useful:

- Make Integration between comments on Facebook and the project. This is not crowdsourcing, but it’s building a community round your project, interacting with the users, and crossing the line to crowdsourcing.

- Try to make comments from Facebook cases in the project. But be precise. Don’t use everything.

- Check Facebook for existing communities, when you start a new project. Look also other places. If there’s a good community or a NGO, consider how you can be part of that.

- Document and publish your data, webtv, pictures under creative commons. A good type is “Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike”.

- Put up a system where it’s very, very easy to contribute with whatever kind of stuff you need.

- If it’s analyzing documents or data, make some awards and other good stuff to make it attractive to do as much as possible. Credit the contributors for their work.

- On the other hand, make it also possible for people to contribute without becoming public. Be sure to have a system to protect sources.

- Try to figure out some more ways to make it a good idea for people to contribute. What is in it for them.

Literature

Wired, June 2006: “The Rise of Crowdsourcing”

Louise Thomas, may 2008: ”Spotlight – Crowdsourcing”

Clay Shirky, Penguin Press, 2008: “Here comes everybody”

Tord Selmer-Nedrelid, March 2010: ”Crowdsourcing – nettdugnad som journalistisk metode”