Frontline investigative reporter Martha Mendoza leads a GIJC25 panel on the global scam industry. Image: Samsul Said, Alt Studio for GIJN

“Raise your hand if you have been approached by a scammer in any way,” said Frontline investigative reporter Martha Mendoza, moderator of the “Scams and Scammers” session during the 14th Global Investigative Journalism Conference (GIJC25). Most of the attendees raised their hands.

“Now turn to the person next to you and tell them how you were approached by a scammer,” she added, and the murmur of stories filled the room.

Law enforcement, governments, social media platforms, and even most newsrooms don’t fully commit to fighting the growing scourge of online fraud, even when scamming is spreading on par with drug trafficking and causes serious financial and emotional damage.

But journalists like Lian Buan, senior investigative reporter at Rappler, Emmanuel K. Dogbevi, founder and managing editor of Ghana Business News, Paul Radu, cofounder and head of innovation at OCCRP, and Mendoza are using data journalism, mapping, whistleblowers, undercover work, and traditional reporting methods to reveal a criminal activity that, according to the Global Anti-Scam Alliance, siphons US$1.03 trillion a year globally.

“And if you think about the lack of restrictions on cryptocurrency combined with the rapid development of AI, the place where these scams are going is quite frightening,” Mendoza noted.

Detecting Scams

When suddenly there was a boom of PhDs in Ghana, and businesspeople who had money or were politically connected began insisting on being called “doctors,” Dogbevi sensed something was amiss.

“They go to events to speak, and everybody introduces them like ‘Doctor So and So,’ but they do not exude that kind of sense of someone with a proper Ph.D., so I decided to look into it,” Dogbevi said.

After an acquaintance revealed the name of the so-called university from which he received the Ph.D., Dogbevi found its email and physical address online. But a Google Maps street view search revealed that, instead of a higher education institution, the address shown was just a dump site in London. Digging deeper, he reached out to the company by email asking how he could get a Ph.D. and received an enthusiastic reply with a list of prices and degrees, and an offer to get a Ph.D. after taking a one-week marketing seminar in Dubai.

After Dogbevi’s team revealed the scam, Ghana’s Ministry of Education announced a crackdown.

Some helpful tips:

- Trust your instincts: Although we may also be victims, investigative reporters usually have a keen eye to spot the small incongruities that are the tell-tale signs of a scam. That’s why scammers try to target society’s most vulnerable — the elderly, the ill, the lonely.

- Pull the thread. Find their addresses with mapping software, and conduct web searches on any names you find. Then reach out, talk to someone, and maybe pose as a client, but stay safe: don’t use traceable numbers, email addresses, or IPs.

To detect scams, OCCRP’s Paul Radu also suggests you ask yourself the following questions:

- Does the activity make unrealistic investment promises?

- Are there high-pressure sales tactics that insist on you wiring or transferring money — or making commitments quickly?

- Are fake names and identities being used by brokers?

- Are investment firms that claim to be regulated actually unlicensed?

- Once someone invests funds, do they have difficulties withdrawing their money?

- Are there complex money movement methods?

- Does the process insist on your bypassing fraud-detection systems?

- Are you forced into using digital-only banks and cryptocurrency?

If the answer to any of these questions is “yes,” dig further. You may be on the path to revealing a scam.

Exposing Scamming Structures

Once you’re certain you’ve detected a scam and you’ve collected initial information, it’s time to determine how far-reaching the structure is. Your run-of-the-mill scam might be operated by very large transnational operations linked to criminal syndicates, which involve other kinds of criminality, like money laundering, fraud, political corruption, human trafficking, and forced labor.

Mendoza described guarded compounds in Myanmar that look like business parks, with hundreds, thousands, or even tens of thousands of people conducting phone and online scams with servers connected to Starlink. Southeast Asia workers with English skills are tricked into working in IT, then smuggled into Myanmar, and their income, which usually comes from scamming victims, is mostly spent within the same compound — in stores and with sex workers that are also trafficking victims.

As with other crimes, scamming snowballs. Small-time criminals might soon find out that they cannot operate without yielding to a larger ring, a more powerful criminal, or needing underground “angel investor” money to take their scam to the next level.

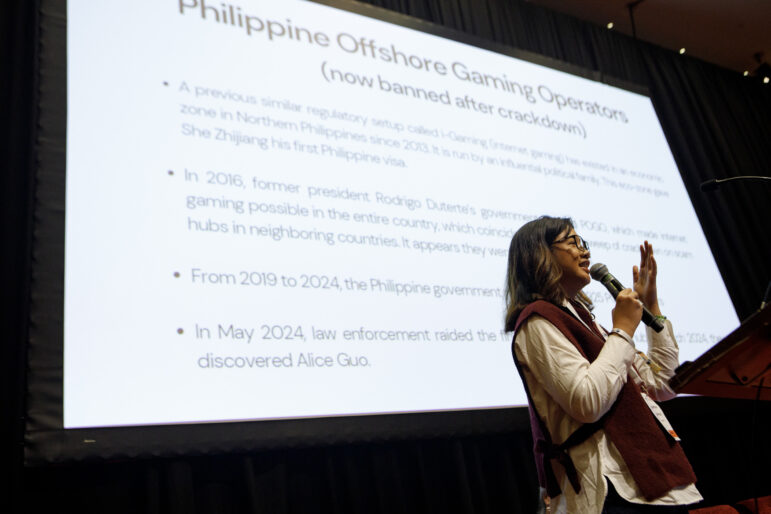

Scamming operations may also be linked to high-level politicians. Rappler’s Lian Buan described how Alice Leal Guo, a Chinese woman who posed as Filipino, ran a rapidly growing scam hub, the Philippines Offshore Gaming Operators (POGOs), from a town where she was mayor. “When I got assigned POGO, I wanted to know who in the government did this. I’m very cynical that way. I always think that there’s some powerful person behind this,” Buan said.

Her reporting revealed links between POGO and the Duterte government, and in a rare instance of accountability — for a crime with alarmingly high levels of impunity — Leal Guo was sentenced to life imprisonment for human trafficking.

Rappler’s Lian Buan discusses her investigation into a scam operation’s links to the Philippine government at a GIJC25 panel. Image: Samsul Said, Alt Studio for GIJN

Here are more tips from Buan:

- Scamming is a shady world — so try to talk to shady people. Maybe someone’s looking for redemption and might give you some insight and introduce you to others, but don’t entirely believe their narrative. Fact-check and corroborate.

- Map a timeline of how the scam operations evolve and cross-check it with policies and high-profile public officials’ statements about the issue. Officials may say one thing but do another. In the Philippines, while then-President Rodrigo Duterte was declaring a war on online gambling, his government was awarding unprecedented numbers of visas to POGO workers and relaxing regulations. Another example: Myanmar’s government recently touted its campaign to tear down the notorious KK Park scam compound, but in reality, the effort looks to be a mostly performative, public relations scheme.

- Try attending legislative and judicial hearings on scamming and talking to the aides, prosecutors, investigators, and assistants involved. Your chance might come up late into the sessions, when most observers and journalists have already left. Buan presented herself as an investigator, not a reporter, and received valuable information and documents.

- Reach out to investigators in supervising institutions like the US Securities and Exchange Commission. They may empathize with your work and support it.

- Drop every document in Google Pinpoint so that even JPG files can be searchable.

- If you do physically go to a scam facility, be more wary about taking photographs of any documents than of the facilities — the official footage will have that.

- Stay with the story. When the initial POGO story had died down, Buan went uninvited to a POGO hub closing ceremony and got on record that it had been owned by the Justice Secretary, amongst other current and former officials. This confirmed her hunch that powerful political figures were behind the operations.

- Cooperate with other media. Buan obtained useful information and sources outside the Philippines by working with OCCRP.

OCCRP’s Paul Radu highlighted the challenges of investigating scams that operate as very wide criminal networks, and the importance of collaboration in reporting on them: “It takes a network to fight a network,” he explained. And to understand how that network is set up and operated, he suggested thinking like a criminal.

Questions to drive your reporting:

- What would you need to gather information about possible victims? Maybe you require OSINT researchers to make a list of those most vulnerable to your scam. For example, people who are grieving for loved ones and might be cognitively impaired or vulnerable to emotional exploitation.

- What technical and physical infrastructure, workers with what backgrounds and skills, do you need? Does it require around-the-clock monitoring? And what kind of access might you need to dark markets or illicit transactions?

“For criminals, this is a business, and crime is a commodity. They can buy packages to conduct these kinds of crimes from the black market, such as stolen identities, fake personas online, and malware,” said Radu.

A key point: once criminals set up scamming centers, they start earning a lot of money, and will need to launder the money and access other criminal systems. In a rapidly growing business they’ll need police and politicians to look the other way, and if they expand, they’ll need that in more than one country, and a small operation will become a criminal network like the one OCCRP exposed with its partners in their transnational investigation, Scam Empire, a collaborative effort by dozens of media partners that looks into the heart of this dark industry.

Making Your Scam Investigation More Impactful

Even if the data is financial, the stories are human. Behind each scam is a person who was psychologically abused, maybe even tortured, and whose money, sometimes their retirement fund or their life savings, was taken from them through blackmail or deceit.

The panelists urged the assembled reporters to use their coverage to demand better guardrails and accountability from governments, tech companies, and institutions that enable scammers through direct business support or overly lax regulations and policies. Also, to push for asset seizure operations that could restore victims’ lost funds. In many cases, the authorities know or can find out where these assets are.

If enough media outlets coordinate a worldwide simultaneous release of stories that shakes public opinion and discourse in the same way the Panama Papers did, maybe law enforcement, legislators, and companies will be forced to act, and accountability will come to bear on a pervasive criminal empire.