Illustration: Siddhesh Gautam for GIJN

Guide to Investigating Land Conflicts in South Asia

Read this article in

The South Asian region, which includes India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, the Maldives, and Pakistan only contains about 3% of the world’s landmass, but hosts 22% of the world’s population, 15.5% of its plant species, and 12% of its animals. Almost 750 million people directly depend on the land for their livelihoods in a region that hosts some of the world’s fastest-growing economies which, in turn, rely heavily on natural resources to power their economic growth.

However, the scarcity of land in South Asian countries naturally leads to domestic conflicts between local communities, businesses, the political class, and the administration over the use and ownership of land and its natural resources. These often escalate into conflicts that particularly affect marginalized communities, have clogged the courts, and frozen unprecedented amounts of investment. Sometimes these conflicts also turn violent — people get killed and property destroyed over these issues.

Land conflicts have a broad impact, too. For example, in Bangladesh, research in 2023 showed that just 34 land conflicts centering on about 11,000 hectares (27,200 acres) of land involved more than 51,000 households. In Nepal, while an estimated one quarter of its 27 million people are landless as of 2023, there are 49 land conflicts involving almost 19,000 households centering on almost 6,000 hectares (14,800 acres) of land there.

In Pakistan, land conflicts are widespread, with at least three million people displaced in former Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) facing ongoing disputes over land ownership, often escalating into armed clashes. In 2023 alone, violent land disputes in the Kurram District in northwestern Pakistan led to more than 130 deaths.

Meanwhile, in India, there are more than 900 ongoing land conflicts, involving 10.5 million people and more than 4.7 million hectares (11.9 million acres) of land, affecting investment worth US$411.4 billion, according to Land Conflict Watch, an independent network of researchers who focus on natural resources.

This guide equips journalists with the tools and resources to report on conflicts over land and its resources such as water and forests. Also, this guide will help journalists answer basic questions such as: what is causing land resource conflicts what is the scale of its impact; who is impacted; who are the actors involved; and how do their motivations shape these conflicts. Moreover, it helps journalists to use such information to tell impactful stories.

Why Is It Important to Report on Land Conflicts?

The prevailing class and caste divide in many South Asian countries and sometimes arbitrary rules have led to irregularities in how access and control over natural resources are regulated. This, in turn, has led to extreme concentrations of wealth, which has left a large segment of society without resources or a livelihood, pushing these individuals to the socioeconomic margins, while leaving them increasingly vulnerable to emerging threats such as climate change, food and water shortage, disasters, pandemics, war, and human rights violations.

Reporting on land and resource conflicts gives journalists an opportunity to delve into the root causes that have led communities such as the Dalits — a community outside of the caste system, previously known as “Untouchables” — to end up on the fringes of society.

Definitions and Concepts

While reporting on land conflicts, it is important to understand certain concepts to be able to report accurately, and to use appropriate terminology to avoid any inadvertent prejudice.

Before starting an investigation, journalists should determine the extent of the conflict by examining how many individuals/households have been affected by the conflict and how; whether the land is private or common; and who has the legal rights to the land. Also, try to ascertain how government authorities handle those individuals or communities without legal ownership of land as well as forest dwellers and tribal communities.

What Is Considered a Land Conflict?

A land conflict can be defined as any instance in which two or more parties dispute the use, access, or control over land and its associated resources. A land conflict arises when there is either a demand for, or opposition to, a change in the ownership, access, or use of land. Since the objective of the guide is to report public interest stories, we will be only discussing land conflicts, where at least one of the parties is a community (public). Property disputes between two private parties are not within the scope of this guide.

Who Is Affected?

How critical or significant the land conflict is will depend on how many people have been affected and how. A land conflict can have large repercussions on the communities who reside on the land or depend on it for their livelihoods, for example, communities can be displaced or forcefully evicted. Many of these conflicts involve the acquisition of agricultural land, with one party or more making allegations that their consent to the appropriation of the land was not obtained or that they were unfairly compensated.

When investigating a story, it is not enough to specify how many individuals or households have been affected by a land conflict. Be detailed. Investigate how exactly it is causing a problem for the community: Are people being displaced or evicted? Are they losing their land or their livelihood? Will they be compensated? Is the compensation enough to start again somewhere new?

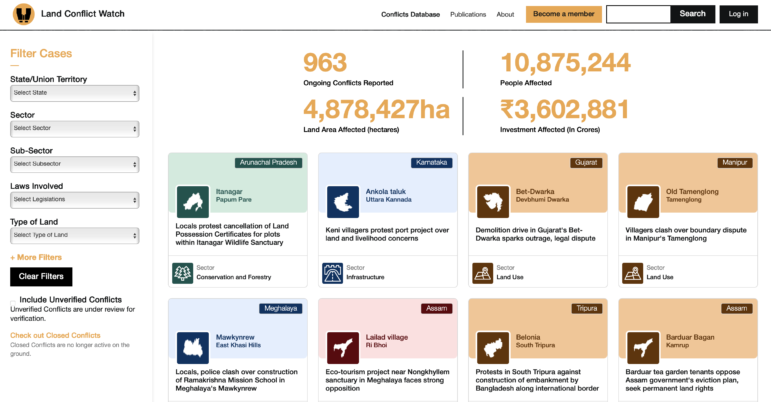

Online resources like Land Conflict Watch can help reporters identify individual land disputes as well as national-level impacts of these conflicts, across metrics like total number of disputes, population and land area affected, and monetary values. Image: Screenshot, Land Conflict Watch

Private Lands and Common Lands

Private land is land that a private party — an individual or an institution — owns legally.

Common lands are those that are collectively managed and used by communities. These could be grazing lands, community forests, bodies of water, for example, that communities use for habitation, livelihoods, or for cultural or religious purposes. Common lands, in most cases, have no formal ownership titles.

Note that in most countries that have a colonial legacy, “common land” is not a legal term and could be referred to under different names. For instance, there is no single category or classification of land use in India that corresponds to common lands. In land records, such land is often classified as forest land, grazing land (known by different names in different jurisdictions), “gram sabha land,” “gram panchayat land,” “municipality land,” or simply “wasteland” or “government land.” These tenurial records are marred by discrepancies and inconsistencies, and often lack data on the current usage of land, including the traditional rights and practices of communities.

Meanwhile, communities claim ownership over these lands often not by exercising legal rights but traditional rights, for example, when they have been cultivating it for generations without any formal land titles. However, the administration often treats these lands as “government-owned.”

This discrepancy results in land conflicts when the government exercises ownership over a plot of common land and unilaterally changes the use of, and access to, such lands without acknowledging communities’ traditional rights over it. Studies show that the majority of land conflicts arise out of this specific type of conflicting claims.

Encroachment

Encroachment generally refers to the process in which a person occupies another person’s land or property without permission. In Indian statutes, encroachment is often defined as the setting up of temporary, semi-permanent, or permanent structures on another person’s land for residential, commercial, or other use. The courts unequivocally recognize the act of encroachment on both private property and public lands as illegal. Unfortunately, this process also ends up labeling individuals or communities that have traditionally used common land but do not have formal titles to the land as “encroachers.”

Illustration: Siddhesh Gautam for GIJN

For example, this happens sometimes to nomadic communities in India. Generations of these communities have moved from one place to another with their cattle, in search of grazing lands. However, many of these communities were classified as “criminal” under the Criminal Tribes Act by the colonial British government in 1871. After the act was repealed in 1945, these communities became known as “Denotified Tribes,” or DNTs. Even so, these groups have had little protection when it comes to land rights, unlike many other marginalized tribal communities such as those that are part of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes categories under the Indian Constitution.

Whenever these nomads use common land, they claim traditional rights over it. The state, on the other hand, considers them encroachers because they have no legal rights to the land, which the state considers government land. The absence of a title to land or laws to safeguard their interests have left these nomadic communities vulnerable to forced evictions, resulting in homelessness and also criminal prosecution.

As a result, it’s important to be aware that the term “encroachers” could be used to label a party in a land dispute as a way to undermine their claims to the land.

For example, often the media or the government label individuals or communities as “encroachers” even though they may have legitimate claims to the land in question because of traditional rights. It is important that in such cases journalists refrain from using the term “encroachers” and instead use the name of the community.

Tips and Tools

Understand the Nature of Land Resource Transactions

The stories involving land conflicts almost always revolve around a transaction of land or its resources where the access to, use of, or control over the resources change hands from one party to another. A conflict gets triggered when the transactions are forced upon one party or are deemed unfair to it. The conflict could be triggered by a proposed transaction, an ongoing one, or a transaction that occurred in the past. It is important to understand the nature, the timelines, the processes, and the parties involved in these transactions to uncover the real stories.

Break Down the Roles of Various Actors

Typically in land resource transactions, several kinds of actors are involved: Communities/citizens, who are the traditional users, owners, or custodians of land and its resources; businesses, who come in to claim rights over land and its resources; governments, which are the custodians of these resources as well as facilitators and regulators of the transactions involving them; and the arbitrators in cases of conflicts.

It’s important to examine the roles of all parties involved in land resource transactions.

Understand the Regulatory Framework

Before reporting a land conflict story, it is important to understand the regulations that apply to land transactions in a country. Journalists don’t need to know all the granular details of the law, but becoming familiar with key provisions and their implications goes a long way. Lawyers and researchers working on these issues in your country can help.

For instance, the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) Regulation, 1900 that applies to three hilly districts in southern Bangladesh regulates land ownership and use there, requiring special permits for land transfers to non-Indigenous people. It protects Indigenous land rights by restricting land sales without prior approval. In Nepal, the Land Act, 1964, governs land reform, including so called “land ceilings,” which prohibit landowners from holding land beyond a certain amount and mandates government acquisition of excess land for redistribution to landless farmers.

A 2022 rally of Indigenous peoples in Dhaka, Bangladesh, marching in support of their CHT rights and against land grabbing, among other issues. Image: Shutterstock

In India, the appropriation of private land by the government is regulated by the Land Acquisition Act of 2013, which makes it mandatory for the government to obtain the consent of a certain percentage of landowners impacted by the appropriation. It also requires that the government conduct a Social Impact Assessment Study before taking over the land, and ensures compensation and resettlement for the displaced. Similarly, when forest lands are diverted for industrial use, the Forest Conservation Act of 1980 and the Forest Rights Act of 2006 mandate that developers obtain permission from the federal government and obtain consent from the tribal communities residing on the land or using it, while also formally recognizing their land rights before any displacement occurs.

Finding Stories in Violations of the Rules

Often land conflicts occur when policies, laws, or rules are violated, subverted, or changed to benefit one party over the other. Sometimes, the existing regulatory framework is perceived as unfair by some parties to a dispute in protecting their rights.

Case Study: This story by the Centre for Investigative Journalism in Nepal (CIJN) highlighted how an amendment in the country’s forest law allowed private wealthy individuals, including members of the ruling party, to buy land in previously protected areas. The government told journalists that previous laws hindered development and that the changes made were an attempt to redistribute land to the landless.

Another investigation by CIJN reported that local government officials misused a new law giving them the power to issue land titles and transfer ownership, fraudulently selling off individuals’ land without their consent. Those accused denied the allegations.

India’s 2006 Forest Rights Act stipulates that forest land cannot be diverted for industrial or commercial use without first formally recognizing the rights of the forest dwellers and then obtaining their consent. An investigation by IndiaSpend in January 2019 found that this provision was being violated by developers to gain access to forest lands. Local authorities claimed that there were no tribal communities or forest dwellers living in the area, or they issued false certificates claiming that forest rights had already been dealt with and that the project was unopposed. The corporate entities accused of wrongdoing didn’t respond to the reporters’ requests while the government officials claimed they followed “due process.”

Documents and Resources

To illustrate how the rules are being bent or broken, documents and other evidence are essential. Journalists can obtain executive orders, minutes of official meetings, and official correspondence from government departments regarding land resources regulations and transactions using Freedom of Information laws. Court documents such as petitions, affidavits, orders, and judgments can also be helpful in finding information and data, as well as parliamentary proceedings, including question and answer sessions. These can be searched online in most countries.

For instance, in India, Parivesh, the project clearance dashboard, where environmental approvals for development projects are published by the Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change, is a great example of an online database where data and documents about land conflicts are stored. Land Conflict Watch is another resource that journalists and researchers can use to access data and documents about land governance. (Editor’s Note: The writer of this guide is the founder of Land Conflict Watch.)

Most governments have now started to digitize land records — ownership deeds, surveys, transaction details — and have started making available the details of land ownership and land transactions online. These land record portals are a valuable source of documents for investigating land ownership and property transactions. For instance, in India, most provinces have online portals where land records and property transaction details for a specific location and for a specific time period can be downloaded. Old maps, revenue receipts for land taxes, even court notices and summons or penalty receipts for encroaching on land have often served as evidence for communities to show historical possession of land, such as in this case of forest land disputes in southern Rajasthan. Journalists should think out of the box and look for such evidence to substantiate their stories.

Use of Satellite Imagery

Satellite imagery can also be a powerful tool for journalists investigating land conflicts, enabling them to visualize disputes with evidence of changes in land use over time. High-resolution imagery, from platforms like Google Earth Pro or NASA’s Landsat, allows reporters to monitor deforestation, encroachment on common land, or shifts in agricultural patterns that often underlie conflicts. For instance, journalists can use historical imagery to document the clearing of forested areas or the expansion of mining operations. Organizations like the European Space Agency and Planet Labs offer resources and tools for accessing satellite data. Additionally, platforms like Google Earth Engine enable journalists to analyze large-scale geospatial datasets, helping them uncover trends and patterns in land-use changes.

By overlaying property maps or “protected forest area” boundaries on satellite images, reporters can reveal realities on the ground. Tools like Mapbox and OpenStreetMap allow for the integration of local mapping data with satellite imagery, adding a layer of context to stories.

Reporting Land Disputes Holistically

Land conflicts do not exist in isolation, they involve a range of other societal issues. Understanding and reporting on these holistically is crucial, as it allows for more comprehensive coverage, reporting that goes beyond surface-level disputes. Here are some key areas where these intersections manifest along with case studies illustrating them.

Land and Politics

Land conflicts often have deep political underpinnings. Politicians may amass wealth by building real estate empires and political parties may exploit land issues for electoral gains, leading to tensions between local communities and state authorities. Reporting on these dynamics can reveal the complex motivations behind land conflicts and highlight the role of the regulatory environment in shaping outcomes.

Case study: In this undercover investigation, Al Jazeera journalists reported on how Bangladesh’s former land minister, Saifuzzaman Chowdhury, allegedly spent more than US$500 million on luxury real estate in London, Dubai, and New York City, but did not declare his overseas assets on his Bangladesh tax returns. Chowdhury said that the funds used to buy these properties came from legitimate businesses he had owned outside Bangladesh for years. As of June 2025, his assets have been frozen by the UK’s National Crime Agency (NCA) and he is under investigation by Bangladesh authorities for money laundering.

The Indian Express investigated more than 2,500 land registries across 25 villages near the Ram temple in Ayodhya. The temple became a major political plank and journalists found a 30% rise in the number of land transactions after the Supreme Court allowed the construction of the temple. According to the Indian Express, many of these deals were allegedly made by family members of politicians and government officials or those closely linked to them across party lines.

The response to these allegations varied amongst the individuals named. Most of them denied any direct involvement in the purchase of land, while others minimized their purchase by stating it was for a school or helping a poor family.

Land and Business

An investigation by Pakistan’s Dawn newspaper documented the illegal expansion of a community beyond its approved borders. Image: Screenshot, Dawn

The interests of private enterprises often clash with those of local communities, particularly when land is repurposed for industrial or commercial use. Journalists should investigate how business interests influence land transactions and assess the impact of these decisions on affected communities.

Case study: This investigation by Pakistan’s Dawn newspaper focused on alleged financial corruption in the development of Bahria Town, a gated community on the outskirts of Karachi. The story showed how the town had been expanding, violating a 2019 Supreme Court judgment that only allowed the project a specific acreage. It also highlighted how the real estate company hadn’t paid a court-mandated fine. The story used satellite mapping to show where the development had encroached on land outside its approved borders.

In court, the company denied exceeding its development outside the land allotted to it after the 2019 judgment. In April 2025, the National Accountability Bureau (NAB), which was investigating the case, froze the company’s assets and issued arrest warrants for the owner.

Land and Caste

In South Asia, caste dynamics significantly influence land ownership and access. Historically marginalized groups often face additional challenges in asserting their land rights. Understanding these nuances can enhance reporting and bring to light the social injustices that underpin many land conflicts.

Case study: This investigation on the ground in many Indian states found that land titles given to Dalits as part of past land redistribution programs have been rendered ineffective because the original owners, who were members of higher castes, never ceded control over the land.

Land and Technology

As many countries in South Asia strive to digitize their land records, new stories are emerging about land issues and technology. On the one hand, technology can improve transparency in land transactions and enhance services related to land for communities. On the other hand, it can exacerbate inequalities, especially if marginalized groups lack access to digital resources.

For instance, in India, the Digital India Land Record Modernisation Programme is being implemented to digitize, update, and safely store land ownership data across the country. It has led to the purging of hardcopy land records and the modernization and digitization of land governance systems. However, this push to use technology solutions for the country’s land problems has also led to disruptions and an emerging area of conflicts.

Case study: This investigation by Down To Earth found that land records were forged during the digitization process of records in order to take land belonging to Dalits in India’s Madhya Pradesh province.

Land and Climate Change

Displacement or migration caused by climate change-related disasters, such as floods or droughts, can lead to disputes over land rights and access to resources. Journalists should investigate the existing policies and government action to address the losses of those affected by climate change. For instance, hundreds of thousands of people are affected by floods in India’s Assam province every year, but a lack of compensation or assistance for these people often leads to new conflicts.

While such stories have traditionally been reported, there are new kinds of land conflicts emerging, which are triggered by “solutions” to mitigate climate change. For instance, large-scale renewable energy, carbon offset, green hydrogen, or rare earth metals/minerals mining projects can also lead to land conflicts if their social and environmental impacts are not properly assessed and mitigated.

Case study: This investigation by India’s Article-14 revealed how land conflicts can arise if climate solutions such as critical mineral mining are allowed without consideration of the land rights of communities. In this case, the local government assured the villagers that there was no threat to their land but their village was nonetheless included in an auction for mineral exploration. Similarly, this investigation by Frontline magazine showed how a solar power plant allegedly appropriated the land of several Indian farmers without their consent or any compensation. Officials had claimed that the proposed land area “remained uncultivated and (was) lying vacant.” The company said it had “purchased the land from bonafide land-owners.”

Editor’s Note: Dilrukshi Handunnetti and Miraj Chowdhury contributed to this guide.

Kumar Sambhav Shrivastava is an award-winning journalist, researcher, and social entrepreneur who specializes in innovative research methods for accountability and equity-based reporting. He is the founder of Land Conflict Watch, a data research initiative that tracks land and environmental conflicts in India. In the past, Kumar served as India Lead for Princeton University’s Digital Witness Lab and was an AI Accountability Fellow with the Pulitzer Center. He has written for international and Indian publications.