Why Journalists Need to Think Like Designers

I had a terrifying realization during the first semester of art and design school. It happened during one of the first group critiques of my work. I had made a sculpture out of found objects, to make a point about about throwaway consumer culture.

One professor said, “This might be better realized as a large, immersive installation.”

Actually,” said another professor, “I would prefer it as a design book with a series of pages with flattened objects.”

“I see it more as a performance,” said a fellow student.

At that point it dawned on me that my idea could possibly take on an infinite number of forms. It could be a sculpture, a room, a book or a performance. This was both a daunting and a dazzling moment of revelation.

It turns out that the whole practice of art and design is about making decisions – both small and large – about the best way to give ideas form, for particular audiences, in particular situations. But how do you learn how to make these decisions?

As Heather Chaplin, director of Journalism + Design at The New School in New York says, “Design is… a practice of invention: It offers processes and strategies for grappling with the uncertainty and fear that come from working in hard-to-define problem spaces with as-yet-determined solutions.”

Design, in this case, does not mean layout. This is design as systems thinking.

Chaplin believes that journalists can leverage design methods for addressing systemic problems like environmental degradation, corruption, racism and gun violence. Design methods help to map their complexity.

“One thing designers spend a lot of time with is problem definition,” says Chaplin. If you set aside assumptions and spend time exploring the problem or issue, “it will change the story and how you tell the story.”

Defining the problem from a systems perspective can help journalists and news organizations understand their role within those systems and what form their intervention might take.

In Top Form

Form is not typically a word used in J-schools nor a subject of journalism trainings, but individual reporters are making design decisions – which medium? which platform? which community? – now more than ever before.

For example, if a reporter is putting together a story on the environmental health impacts of industrial pollution in the US working-class town of Chelsea, Massachusetts, should her story be a long-form narrative? A live blog, accounting her process of discovery? A twitter chat connecting the global communities whose goods travel through Chelsea? A podcast featuring guest experts? A bot that sends readers alerts every time a new environmental permit is issued in Chelsea? An interactive documentary where you can travel Chelsea’s 2.2 square miles in virtual reality? A slideshow with powerful photos of the struggles of Chelsea residents? An in-person community storytelling event that brings together diverse stakeholders from industry to advocacy?

Some nonprofit newsrooms, documentary producers and online publishers have always had to think about form and engagement in multiple ways. But to other journalists, these possibilities may feel overwhelming and unfamiliar. And all newsrooms don’t have equal resources and the luxury of time to understand an issue from a systems perspective and produce interactive and visual content that intervenes in that system.

Tando Ntunja, a lecturer who teaches interactive media at the University of Cape Town, describes the day-to-day newsroom environment in South Africa as “risk-averse.” But, there are occasions where an ongoing story opens up the time and space for more experimentation. For example, in March 2015, wildfires were raging for several weeks in Cape Town.

“Eyewitness News created this crazy interactive documentary that was tracking the fires during that period,” says Ntunja. “It became an opportunity for them to show they could do this kind of stuff.” Though Landi Groenewald, product strategist at EWN, characterizes their dev and design team as “scrawny,” their documentary – Scorched Earth – won a number of awards. It was also accompanied by supplementary photo features for mobile audiences on Facebook and Instagram.

“Eyewitness News created this crazy interactive documentary that was tracking the fires during that period,” says Ntunja. “It became an opportunity for them to show they could do this kind of stuff.” Though Landi Groenewald, product strategist at EWN, characterizes their dev and design team as “scrawny,” their documentary – Scorched Earth – won a number of awards. It was also accompanied by supplementary photo features for mobile audiences on Facebook and Instagram.

Developing the Design Mindset

People covering crisis situations in journalism did not have to worry about decisions like “interactive documentary vs Twitter feed vs live blog?” too much in the past. Take a typical print journalist from 40 years ago. Her job was to deliver copy. This would likely involve doing background research, interviewing people, developing an angle and writing the story.

She did not have to think about when to publish the story – that was given by the schedule of the newspaper. She did not have to think about where the story would go in the paper – that was the editor’s job. And the spatial layout was clear – it would be a vertical column of black and white words of a certain length. That was fixed by the format of the paper. She did not have to think about who was reading the story because it was clearly the subscribers to the paper and they were handled by the business side of the operation.

But in the digital era none of these things are given. Journalists are, for better or for worse, thinking about aspects of the digital news ecosystem like medium, audience, and distribution that were previously considered very, very far outside their job description.

This is where the skills of the designer bring methods and mindsets to bear that can help to navigate the complexity. Following is a list of some of the most helpful design methods and mindsets that journalists can start to borrow from designers.

Systems Thinking

Designers think of their artifacts not as perfect objects that exist in isolation but rather as imperfect interventions embedded in complex human systems that try to improve something specific about the world. This can also apply to news stories.

As Chaplin says, “I’ve come to see every news story as a system.” That system includes the words and content, of course, but also the places the story travels across the internet, the conversations it generates, the people who read/experience/interact with it, and the actions it catalyzes in the world. The question becomes not “What is a news story?” but “What does a news story do?”

Experimentation and Iteration

Giving form to ideas and integrating that into existing systems is a messy process and designers know they never get it right the first time. Designers have extensive methods for prototyping and testing ideas while in process, ranging from rapid ethnography to co-design to paper prototyping.

Rather than investing large amounts of time and money into giant projects only to realize that your original assumptions were flawed, an ethos of experimentation permits learning, failure and dialogue with your audience along the way.

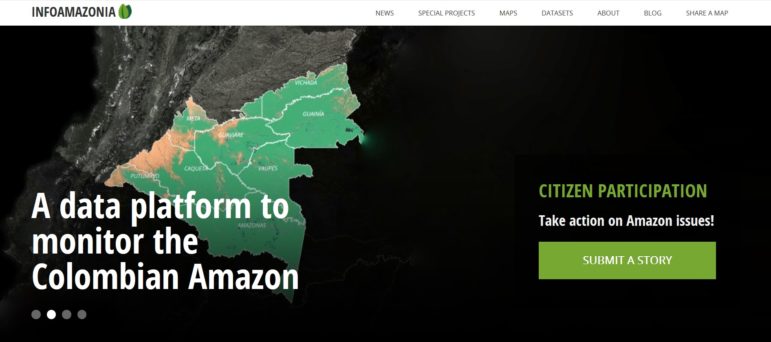

For example, Ntunja recently challenged her students to create multilingual interactive news projects to account for indigenous South African languages. But she admits that experimentation is very difficult to do in a day-to-day newsroom, “It’s more feasible to experiment with special projects and in the classroom.” Undertaking experimentation may mean organizations need to look outside their subscriber base for funding; the environmental data journalism site InfoAmazonia was launched by Brazilian journalist Gustavo Faleiros, who partnered with NGOs to crowdfund much of their work.

Aligning Form and Content

Designers have a sophisticated understanding of the interplay between form and content. They talk about “affordances” and “constraints” of different mediums. For example, if one of your goals is to spark deep, reflective conversation on a complicated policy issue, you would likely not choose Twitter as your medium because brevity is one of its constraints. Likewise, a single 500-word news story published on a single day can’t fulfill the goal of holding powerful figures to account for campaign contributions in an on-going way.

Miguel Paz did this in three Latin American countries with Poderopedia, a constantly updated database of powerful politicians and their voting records. In this case, the form chosen matches the goals of the designer.

Expansive Thinking on Engagement

Social media, mobile phones and comments have drastically transformed the relationship between publishers and the “people formerly known as the audience.” Newsrooms are hiring engagement editors, producing storytelling events and starting to curate communities at scale.

These are not simply ways to garner more eyeballs and marketing revenue. These are design opportunities for architecting fundamentally different relationships between news providers and the communities they serve. Ntunja sees the comments section of a story as a way to study her audience, “Engagements between users create another layer of content that you can use to create other kinds of content. What are audiences invested in and what do they value?”

Journalism + Design

So is there a demand for this kind of thinking? Chaplin’s former Journalism + Design program at Parsons in New York was the second most popular major at the entire school.

But how can we create educational opportunities for working journalists in a global context to learn about design methods and mindsets? The work of bringing two distinct fields of practice together is mostly happening in an ad-hoc way, in the individual teaching practices of many early-career journalism lecturers such as Ntunja and the innovative projects of entrepreneurs like Paz and Faleiros. But we should work collectively, as a field, to start to see more strategic and systematic connections between journalism and design, across professional trainings as well as higher education.

Stay tuned – Chaplin is working on a free, systems thinking toolkit for journalists. “What is primarily valuable about systems thinking to a reporter? It’s learning to map connections and interconnections and identifying leverage points.”

This article was updated after publication to reflect Heather Chaplin’s new role as director of Journalism + Design at The New School in New York.

Catherine D’Ignazio is an assistant professor of Civic Media and Data Visualization in the Journalism Department at Emerson College. She is currently a faculty director at the Emerson Engagement Lab, a research affiliate at the MIT Center for Civic Media and the MIT Media Lab and an organizer with the Public Laboratory for Technology and Science.

Catherine D’Ignazio is an assistant professor of Civic Media and Data Visualization in the Journalism Department at Emerson College. She is currently a faculty director at the Emerson Engagement Lab, a research affiliate at the MIT Center for Civic Media and the MIT Media Lab and an organizer with the Public Laboratory for Technology and Science.