Tracking COVID-19 World Bank Funding by Country

Read this article in

The World Bank is supporting governments in their response to the COVID-19 pandemic, providing about $14 billion to more than 100 countries. But how is the money being spent and who is getting the contracts?

Tracking the use of this money can be facilitated by World Bank data online along with national procurement records.

This resource aims to encourage such inquiries. We’ll show how to mine the somewhat-complex World Bank record system. We’ll also suggest ways to use these documents in conjunction with research into procurement records at the national level.

Also, see a short GIJN video showing how to access World Bank documents about COVID-19 aid to your country.

While the World Bank is among the largest international donors to developing countries, billions more are flowing from other institutions, such as the Inter-American Development Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). (For details, see this article by Devex, the global development media platform. Also, visit donor websites.)

Add in contributions from donor countries and private foundations, and “more than $20 trillion has been committed for the immediate and long-term COVID-19 response since January,” Devex reported. For overview data on donor responses, see a COVID-19 funding tracking prototype, described here.

The Early Warning System COVID-19 DFI Tracker by the International Accountability Project logs project by the major development banks. Tip: you can sign up for an RSS feed of new information it posts about projects your country (these may not include notice of all new project documents).

The World Bank system also will provide email alerts about each country.

Following international projects will still require getting local information, particularly about contracts. See GIJN guidance: Researching Government Contracts for COVID-19 Spending.

Some national procurement disclosure systems need improvement. Concerns about the potential for misuse of the funds, especially when they are dispersed under emergency conditions, have prompted the Bank, the IMF, and other institutions to take steps to improve national procurement processes. Some nongovernmental organizations have urged stronger action.

How to Follow the World Bank COVID-19 Project, Plus Story Ideas

So the spotlight is on COVID-19 spending. And there are many stories that can be done from World Bank records alone:

- Is fraud or corruption diverting COVID-19 aid money?

- What is your country planning to do with the money?

- What goals has the Bank set, and how is your country doing?

- How does the spending relate to healthcare system reforms?

- Is the contracting being done with no-bid contracting or competitive bidding?

- What contracts have been signed?

- Have the procurement plans changed?

- Is the procurement process taking too long?

Here are stories that can be found using World Bank records plus national procurement information:

- Who got the contracts?

- Who is the contractor?

- Were the goods delivered?

- Is the work getting done?

Let’s get started.

A Workbook for Tracking COVID-19 World Bank Funding

There are several Bank programs. This guide deals mostly with the “COVID-19 Fast-Track Facility” which primarily supports national procurement to fight the pandemic. The program includes about 75 countries.

Another program, “COVID-19 Economic Crisis and Recovery Development Policy Financing,” helps about 70 countries, many of them also benefiting from the fast-track program. This program helps more on the financial front, such as support for public works projects or efforts to encourage private investment.

World Bank support for the private sector is channeled through the International Finance Corporation, which has been urged to be more transparent about its beneficiaries.

Part 1: Navigating the World Bank Website

Step One — Does the World Bank Support COVID-19 Procurement in Your Country?

The Bank has an overview page on its COVID-19 response. On that main page, scroll down to the “Resources” box on the left to see which countries are getting support. That page — the “World Bank Group’s Operational Response to COVID-19 (coronavirus) – Projects List”– is kept updated.

The links provided for each country go to press releases that give useful overall information and list contact persons. However, there’s not much detail. Under the “Related” tab on the right side of the individual country page is a link to the Bank’s home page for each country, “The World Bank in Benin,” for example. These home pages are not very helpful in researching COVID-19 funding specifics, although some additional Bank officials are named.

There’s better stuff in other Bank documents. Read on.

Step Two — Finding Specifics on Bank Activity for Your Country

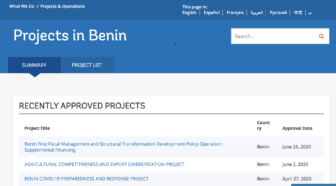

For country-level detail about Bank-supported COVID-19 projects, look here at the projects and operations page. There’s another list of affected countries. Pick a country.

Step Three — Find Documents on COVID-19 Projects in Your Country

Once you’ve clicked on your chosen country from the projects and operations page, you’ll land on a page headlined: “Recently Approved Projects.”

Click on the line that says “COVID-19 Emergency Preparedness and Response Project.” (Or, “COVID-19 Economic Crisis and Recovery Development Policy.”)

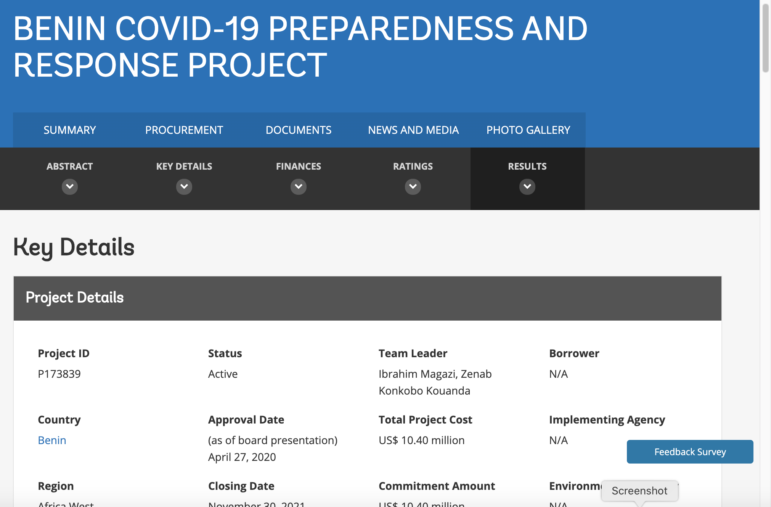

This will bring up a “Project Details” page with general information that includes the total cost and financing source, the team leader, and the project ID number.

While the team leader’s email is not provided, the standard World Bank email convention is: (initial of first name)(last name)@worldbank.org.

Scroll down to see the “Results Framework.” This action summarizes the government’s goals, in 12-20 very specific categories. For example: “Designated acute healthcare facilities with isolation capacity.”

Caution: Confusingly, the numbers in the chart are sometimes percentage and sometimes absolute numbers, a distinction that is not made in the results framework. But it is made in a more complete document we’re about to come to, the “Project Appraisal Document.”

Step Four — Getting Details of the Spending Plan

To get there, click “Documents” in the top bar of your country page’s “COVID-19 Preparedness and Response Project.” (Right where you are now, if you are following along.)

Displayed under “Documents” is a list of everything associated with the project, including “Implementation Status and Results Reports” (ISRs), “Procurement Plans”, “Project Appraisal Documents” (PADs), “Environmental and Social Reviews” (ESRs), and more. These documents are prepared by the Bank in conjunction with the national government.

For the big picture, and some cool details, read the “Project Appraisal Document” (PAD).

Note: The parallel key document for the “COVID-19 Economic Crisis and Recovery Development Policy Financing” is the “Program Document.”

The PAD contains many interesting details. It describes the project goals and lays out the indicators for evaluating success. There is plenty of background information, including the country’s score on a “preparedness” scale. (Recently posted for some countries is a progress report document, ISR.)

For an example, see the Sierra Leone March 27 PAD, or the ISR from July 8.

For even more information, look at the “Procurement Plan.”

For many countries there are multiple versions of the procurement plan, so start with the most recent. (Note: Comparing plans shows items dropped or added.)

Step Five — Examine the Procurement Plan

Once you click on the “Procurement Plan” line, you’ll be taken to a specific page with the document. This document shows exactly what purchases are planned — what clinics will be built or what equipment will be acquired.

The core material is located in a spreadsheet within the document.

Once you figure out how to enlarge the spreadsheet to view the small print, you’ll find:

- A short description of each contemplated contract.

- The estimated amount.

- The contracting procedure. Of note may be the degree to which “no contract bids” (NCBs) and “Direct Contracting” (aka sole source) are used.

- The target dates for bidding notices (where applicable).

- The target dates for contract signing. Some projects may show as “cancelled,” others as “signed,” or “pending implementation.”

However, the spreadsheet doesn’t say who got the contract.

Example: Ghana’s June 18 Procurement Plan.

Step Six — Look Elsewhere on the World Bank Website for More Information

Go back to the “Project Details” page. To get there again, you might need to go back here, pick your country, again choose the line that says “COVID-19 Preparedness and Response Project.”

But this time, in the tabs above, pick “Procurement.”

This page might say “No Procurement Notices available for this project,” or it may display information about tender offers or contracts signed.

For each contract, the information available includes:

- A one line description of the scope of the contract.

- The name of the contractor.

- The address of the contractor.

- The duration of the contract.

- The amount of the contract.

- The bid/contract reference number.

- The date of the contract.

The Bank does not link to the contract itself. So far, there are not too many listings.

Another Bank page, Procurement Results, shows Bank-supported procurement for all purposes, and for which COVID-19 contracts are included. Searches can be narrowed by country, but not by type of project.

However, searches to see only the COVID-19 projects don’t seem to be possible.

Examples of Bank Documents: The Kenyan procurement plan, listing a $4 million contract for ventilators in Kenya.

PART 2: Following Up with Country-Level Research

The World Bank provides a road map for what governments are expected to do with World Bank funds. But, the Bank leaves the local contracting up to individual nations. The Bank collects some information on contracts, but it is incomplete and late. So supplementary in-country research is vital.

For information on a specific country’s laws and procurement agencies, see the World Bank’s database. Pick a country and then choose “Public Procurement Agency” under “Resources,” on the right side.

For information on a specific country’s laws and procurement agencies, see the World Bank’s database. Pick a country and then choose “Public Procurement Agency” under “Resources,” on the right side.

Unfortunately, many national online systems are incomplete and/or difficult to use. Ideally, they should include reference to the World Bank Group project ID (but many may not). Following the procurement process will likely mean reading public announcements looking for tender offers, contract openings, and contract signings.

Transparency gaps may impede reporting. The Bank in agreement with some countries mandated the public posting of only “large” procurement contracts and the names of their beneficial owners. Figuring out the national system will be key to making use of the information from the World Bank.

Note: In some documents, the Bank makes frank and critical comments on the national procurement regime. There are suggestions of country promises to reform.

Longer term, the Bank has mandated audits of the spending, including by third parties. So there may be comprehensive accounting down the road, if the reports get released. In the meantime, there’s plenty to investigate.

Tracking World Bank COVID-19 Spending Through Audits

A variety of monitoring reports will be prepared about COVID-19 spending, some by the Bank, some by third parties, and some by national governments.

Access to them may vary. A few are being released already; others will come later.

Here’s what to watch for:

Reviews Conducted by the Bank

The Bank itself will monitor the COVID-19 projects in a variety of ways, including some innovative new ones.

Emerging already are ISRs. These are quarterly project summaries written by Bank staff based on information from governments. ISRs summarize whether governments are achieving the project’s quantifiable goals, the “results indicators.”

The Bank has said it will monitor COVID-19 projects by Bank staff using a procurement and financial management “SWAT Team,” but has not indicated whether the findings will be made public. Also revealed are the Bank’s plans for a “Geo-Enabling Initiative for Monitoring and Supervision” (GEMS) and an “Iterative Beneficiary Monitoring” approach, but little information is available.

Formal requests for information can be submitted here under the Bank’s Access to Information Policy.

The Bank always reserves the right to investigate government handling of Bank projects to ensure they comply with the Bank’s anti-corruption guidelines. This applies to the COVID-19 projects, but the results of any such probes will not be available for some time. The investigations are handled by the Integrity Vice Presidency, an independent unit within the Bank. Some outcomes are disclosed, but not always with names.

Government Monitoring Efforts Encouraged

Some governments have been tasked by the Bank to hire “third parties” to conduct an “external audit” of projects related to COVID-19.

For example, in Gambia, which will receive about $10 million from the Bank, $11,000 was allotted for the “external audit,” according to the July 15 procurement plan. Asked if third party monitoring reports will be released, a Bank spokesperson said: “Not necessarily, there is no such standard requirement.”

Governments may conduct their own audits too, and the Bank has indicated concerns about whether some governments have capacity to do so, and whether the resulting audits will be transparent.

Will the audits be made public? Maybe not. But learning of their existence is a starting point for asking to see them.

Other Resources

To locate fraud and corruption in government contracts, see the many suggestions of “red flags” in GIJN’s resource guide Researching Government Contracts for COVID-19 Spending. This is also available in Arabic and Bangla. GIJN’s suggestions are summarized in this one-page tipsheet.

A GIJN webinar on investigating contracts featured several journalists and an expert from the Open Contracting Partnership. Also, the Open Contracting Partnership has published a Guide to Collect, Publish and Visualize COVID-19 Procurement Data. OCP’s weekly newsletter includes examples of good journalism on contracts from around the world.

The Bank Information Center, a Washington-based NGO, has produced a database, COVID-19 World Bank Emergency Response: Projects Repository. It is not focused on contracts, but does thoroughly identify COVID-19 spending, including some outside of the “emergency response” projects.

Toby McIntosh is GIJN’s Resource Center senior advisor. He was with Bloomberg BNA in Washington for 39 years. He is the former editor of FreedomInfo.org (2010-2017), where he wrote about FOI policies worldwide. His blog is eyeonglobaltransparency.net.

Toby McIntosh is GIJN’s Resource Center senior advisor. He was with Bloomberg BNA in Washington for 39 years. He is the former editor of FreedomInfo.org (2010-2017), where he wrote about FOI policies worldwide. His blog is eyeonglobaltransparency.net.