Investigating Murdered or Missing Persons

Attacks on Indigenous people worldwide are an important focus for investigative journalism.

However, these stories of personal tragedy contain leads that can inform reporting on wider systemic issues which relate to these personal stories.

Reporters have delved into cold cases, documented the disproportionate numbers of missing and murdered Indigenous persons, and identified underlying causes.

This GIJN/NAJA guide provides examples of good journalistic work done in this area, suggests new avenues to explore, and provides tools and techniques that are useful in covering this issue.

In North America, this topic often goes by the acronym MMIW (murdered and missing Indigenous women) and sometimes MMIWG, with “girls” added. (On Twitter, the hashtags used are #MMIW and #MMIWG.) Largely unknown is the fact that men and boys go missing in greater numbers. See article on missing MMIMB in Canada and data from the US.

The broad categories covered are:

- Crime-Solving: With so many unsolved cases, what can journalists do?

- The Big Picture: What is the scale of the problem?

- The Reasons: Why are abductions and murders occurring?

- Problem-Solving: What is being done?

Photo: Flickr/Lorie Shaull

Crime-Solving

Cree journalist Connie Walker covers individual cases of missing persons but also looks at the issue in a broader context, examining contributing factors such as colonization, racism, and the intergenerational effects of residential schools.

“It was important for us not only to focus on an unsolved true crime case, but also examine the bigger picture,” Walker said in a 2018 Columbia Journalism Review article by Elon Green about her work for the Canadian Broadcast Company (CBC).

Walker’s podcast describes investigative techniques such as finding a gravestone online, identifying an adoption family, and getting policy records, but she also addresses the mindset that guides her work.

“It’s about being respectful of the people that you’re reporting on, but also amplifying voices as opposed to telling stories for people,” she said.

The use of podcasts to dramatize crime stories, also featuring Walker, was discussed in a 2019 High Country News article by Elena Saavedra Buckley.

A look at MMIWG in Montana was undertaken by Sam Wilson in The Billings Gazette in 2019, focusing on complaints about the police investigations.

Investigating Cold Cases

The reported lack of adequate police investigations has led victims’ families and journalists to delve into cold cases.

In Australia, the Australian Broadcasting Company (ABC) investigation Blood on the Tracks put new light on the 1988 death of Aboriginal teenager Mark Haines. This piece led to the case being reopened.

How journalists Allan Clarke and Suzie Smith, who are respectively Muruwari and Gomeroi, unraveled the 30-year mystery of Haines’ death is described in an interview with the two journalists. Also see an article by Amy McQuire about Clarke’s work.

Also in Australia, ABC reporter Steven Schubert looked at two deaths, one in 2007 and one in 2013. He found that “the police made virtually almost all the same mistakes,” particularly by performing shoddy investigations and ignoring evidence.

Examination of individual cases often plays a significant role in illuminating the larger story. Among the many examples:

- Associated Press reporter Sharon Cohen’s 2018 stories: #NotInvisible: Why are Native American Women Vanishing and Haunting Stories Behind Missing Posters of Native Women

- Advocates Strive to Raise Awareness About Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women in the US and Canada, by Public Radio International in 2019

- The Al Jazeera Fault Lines 2019 documentary, The Search: Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women

- The Missing and Murdered: ‘We as Native Women are Hunted’ (2018) by Garet Bleir and Anya Zoledziowski for News21 in partnership with ProPublica’s Documenting Hate Project

Investigative Tools

Few resources exist to guide journalists on searching for missing persons.

A dive into the world of amateur true crime solvers’ work and police manuals turns up some common recommendations:

- Put what you know in order using spreadsheets.

- Create a timeline.

- Look for gaps, inconsistencies, overlaps, and odd bits of information.

- Re-read everything.

- Follow every lead.

- Keep an open mind.

Deborah Halper, a US journalist who wrote the 2014 book “The Skeleton Crew: How Amateur Sleuths Are Solving America’s Coldest Cases,” recommended the US National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs) as a good resource. This database of reported missing persons is searchable and alerts can be provided for updates on specific persons. See PowerPoint instructions. Regional resource experts at NamUs can be consulted for further assistance. Also note a 2019 NaMus presentation, including graphics: Using Data and Research to Address Missing and Unidentified Persons Cases in Indian Country and Alaska Native Villages.

Other countries have comparable official and private organizations.

Halper’s 2014 article, How to Solve a Murder With Just Your Computer, includes five tips:

- Leave no digital stone unturned.

- Invest in paid services.

- Develop a tolerance for rejection.

- Have a strong stomach.

- Think visually.

Another common message: Be persistent.

Creative Techniques

The use of drones and social media to track down missing persons may not have been used yet by reporters, but the possibilities are intriguing.

Citizens conducting independent investigations have used drones. In the Search for Missing Women, Neighbors and Family Members Pair Drones With Indigenous Knowledge, an article by Janice Cantieri in the Canadian publication Yes Magazine, tells the story of efforts by a Splatsin tribal team.

Social media is another way to gather information on this topic.

United Press International reporter Jean Lotus, who is based in the US, wrote a story that drew attention to the use of social media titled ‘Missing and Murdered’: Indigenous Women at Risk in U.S., Canada.

There are also Facebook sites on MMIW cases, including: Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls USA and Lost and Missing in Indian Country.

Media Coverage Faulted

As previously stated, these personal tragedies often relate to larger societal issues, which may include how well the media has handled particular instances.

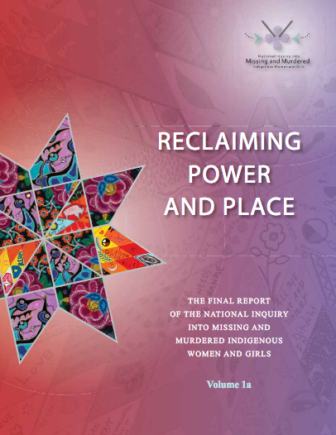

In Canada, the 2019 report on the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls includes many policy recommendations, including the investigation of cold cases. Of note, a whole chapter (see p. 385) is devoted to stereotyping and dehumanization by the media.

In Canada, the 2019 report on the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls includes many policy recommendations, including the investigation of cold cases. Of note, a whole chapter (see p. 385) is devoted to stereotyping and dehumanization by the media.

The higher rates of missing and murdered men and boys has received less press attention and was not part of the Canadian inquiry, but a “holistic model of inquiry” is needed, according to University of Saskatchewan professors John G. Hansen, a member of the Opaskwayak Cree Nation, and Emeka E. Dim.

Among their conclusions, they wrote: “The exploration of Canada’s missing and murdered Indigenous people needs to emphasize social change, where we must consider, among other things, how violence against Indigenous people is influenced by racial inequality, poverty, the effects of colonialism, intergenerational residential school effects, and social exclusion.”

A detailed 2018 report by the Seattle-based Urban Indian Health Institute (UIHI) faulted the US media for being too centered on reservation-based violence and using language “that could be perceived as violent and victim-blaming.”

The UIHI researchers called for more research on root causes, explaining that “many of the reasons commonly attributed to root causes of MMIWG in the media and popular narrative — sex work and domestic violence, for example — are forms of violence that were not prominent in the cases UIHI found, and the geography of this data does not match an assumed perception on where MMIWG cases are more likely to occur.”

Among other things, the UIHI report suggests more work on racial and gender bias in police forces.

See a 2014 review, Violence Against Women and Girls in Canada by Pippa Feinstein and Megan Pearce, which summarizes recommendations from decades of studies in Canada and includes a spreadsheet with links to the studies.

The 1,200-page Canadian report concludes that “the root cause is colonialism, which runs deep throughout the foundational fabric of this country.”

It continues, “This violence is rooted in systemic factors, like economic, social, and political marginalization, as well as racism, discrimination, and misogyny, woven into the fabric of Canadian society.”

The report examines these areas in detail and some of the findings might inform further reporting on root causes.

For example, it states, “There is substantial evidence of a serious problem that requires focused attention on the relationship between resource extraction projects and violence against Indigenous women.”

The Canadian report says recommendations which focus on root causes “have been made many times before, and little has changed.”

There are too few stories that specifically explain the unique experiences of Aboriginal women, wrote Amy McQuire, a Darumbal and South Sea Islander journalist, in a 2018 article in @IndigenousX, We Can’t Dismantle Systems of Violence Unless We Centre Aboriginal Women.

There seem to be few stories in that vein, but see an article published by the Canadian magazine Maclean’s by Kyle Edwards titled How We Treat Women, which examines life in remote work camps.

International Dimension

A number of international institutions are interested in this topic.

The Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) met with United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous People Victoria Tauli-Corpuz to urge her to support efforts to broaden the definition of genocide in international law, as described in Indian Country Today.

Besides the UN Human Rights Office, there are a number of other potential international bodies of note.

The Inter-American Human Rights Commission of the Organization of American States issued a report in 2014 on missing and murdered Indigenous women in the Canadian province of British Columbia.

Violence against Indigenous activists was a topic discussed at the 2019 Bonn meeting of the Global Landscapes Forum, according to a Forest Peoples Programme account. Geovaldis Gonzalez Jimenez, an activist from the region of Montes de Maria in Colombia, said 566 community leaders have been killed in Colombia – including 135 in 2019 alone. According to Front Line Defenders, in 2018, 321 defenders in 27 countries were targeted and killed for their work, which is the highest number ever on record. More than three-quarters of these “were defending land, environmental, or Indigenous peoples’ rights, often in the context of extractive industries and state-aligned mega-projects.”

Sixty-seven percent of the 312 human rights defenders murdered in 2017 were defending their lands, the environment, or Indigenous rights, often in the context of private sector projects.

Alternative Data

Official statistics have often been found wanting, and although some reform efforts are underway, independent data-gathering has emerged to fill the gaps.

“Ill-informed newsrooms often rely on stereotypes of tribal communities, which can result in the exploitation of victims, instead of contextualizing history to produce ethical coverage of Indigenous peoples,” begins a NAJA guide on covering violence against women.

“Though awareness of the crisis is growing, data on the realities of this violence is scarce,” a 2018 report by Urban Indian Health Institute in Seattle stated.

Annita Lucchesi, a member of the Cheyenne Tribe, created a database that includes 2,501 cases in the US and Canada going back to 1900. She continues the effort through the California-based Sovereign Bodies Institute. The lack of official data prompted Lucchesi’s effort, as described in this 2018 article in The Intercept by Allen Brown.

The blog Justice for Native Women collects and displays pictures and thumbnail information on missing and murdered Indigenous women.

The US National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center in 2019 published Special Collection: Missing & Murdered Indigenous Women & Girls, a collection of resources to address the issues of MMIWG.

Journalists have created databases to document the magnitude of the problem and get leads. See a major effort by CBC News with pictures and information about the cases of death or disappearance of Indigenous women that authorities said were not due to foul play. “CBC News found evidence in many of the cases that points to suspicious circumstances, unexplained bruises, and other factors that suggest further investigation is warranted.”

A coalition of Latin-American journalists developed the reporting project, Tierra de Resistentes (Land of Resistors), which examines the dangers that face Indigenous environmental activists.