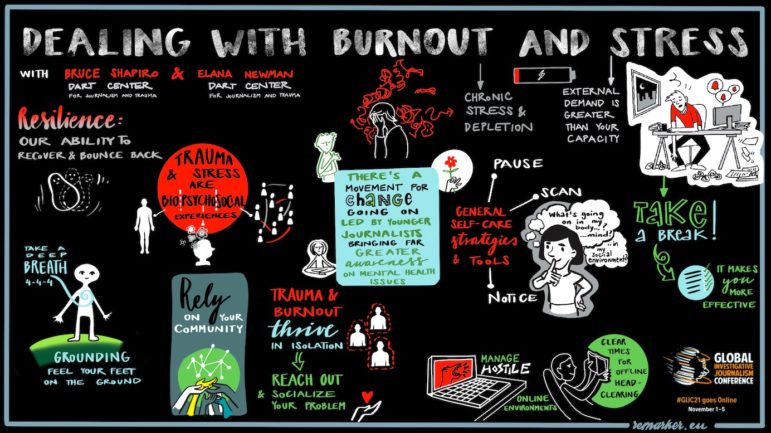

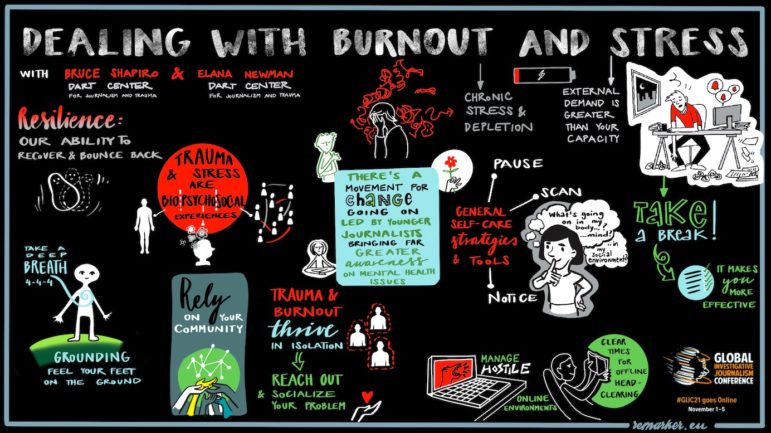

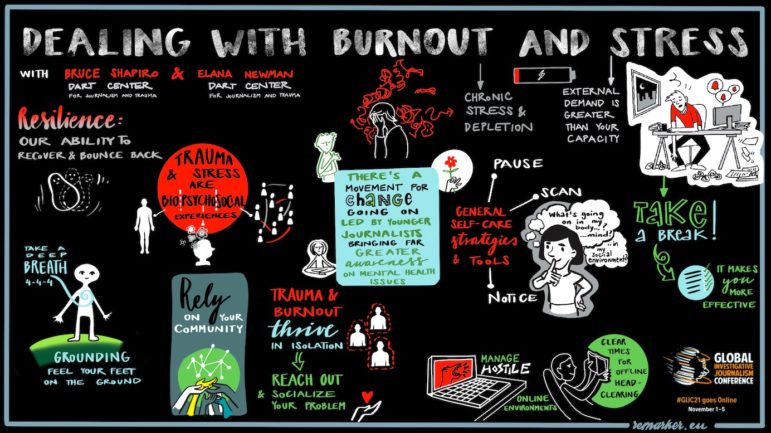

Illustration: Kata Máthé/ Remarker

Resilient Reporting: Tips on How to Cope with Burnout and Trauma

Highlights from Dealing with Burnout and Stress, a session at the 2021 Global Investigative Journalism Conference. Illustration: Kata Máthé/ Remarker

Almost every journalist has contended with the COVID-19 pandemic and its disruptive effects on their lives. Many have directly reported on the impact of the virus while facing challenges like lockdowns, the risk of contagion, increased workloads, and screen fatigue.

Likewise, many reporters still must contend with the usual suspects that cause burnout and trauma, such as emotionally difficult subjects, violence, threats, and graphic imagery.

Resilience is the human ability to cope, bounce back, and adapt after adversity, trauma, tragedy, and significant sources of stress, and journalists may be particularly good at it, according to the experts at the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, a Columbia University project to link journalists, clinicians, and researchers. Trauma exposure in journalism is higher than for the general population, but PTSD rates are comparatively low. Nonetheless, psychological injury can be distinctly harmful for journalists when it happens.

During a panel at the 12th Global Investigative Journalism Conference (#GIJC21), Dart Center executive director Bruce Shapiro and Elana Newman, Dart’s research director and McFarlin Professor of Psychology at Tulsa University, offered practical tips on how to identify burnout and trauma, and how to strengthen reporters’ resilience.

“These strategies for coping are not a substitute for mental health,” warned Newman. “This is more of a psycho-education presentation where we will help you understand some of the stress you may be experiencing, and some immediate skills that may help you with noticing stress levels and then responding to them.”

Identifying Burnout and Trauma

While stress is a normal reaction which cannot be eliminated, and may be beneficial in small doses, burnout is a response to chronic work stress or a result of unmanaged work stress. It may emerge when stress is unremitting, and there is an inability to adjust to it or shut off the stress response.

Trauma involves experiencing or witnessing a life threat, serious injury, or sexual violence. Some of the signals of trauma are similar to those of PTSD. “Trauma has a slightly different biological profile [than burnout], but the point of both of these is that trauma and stress are biopsychosocial experiences, and they have an impact on your biology, your psychology, and your social interactions,” explained Newman.

The following are signals of stress reactions to burnout/trauma divided into their biological, psychological, and social manifestations:

|

BIO |

PSYCHO |

SOCIAL |

| Fatigue, sleep problems | Sadness, despair, anguish | Isolation |

| Trouble concentrating | Anxiety/unease about the future | Irritability/anger |

| Jumpy, edgy feeling | Changed meanings about the world | Withdrawing |

| Trouble breathing | Troubling thoughts, images | Feeling misunderstood |

| Headache, body aches, stomach distress | Dread/sense of foreboding | Feeling lonely |

| Feeling spacy, disconnected | Self-attack | Anxious about contact with others |

Coping with Burnout and Trauma

The tools and strategies to cope with burnout and trauma may be divided according to the three biopsychosocial dimensions, and each individual may decide what tools work better and which don’t.

The first technique involves increasing self-awareness and scanning each domain: What are you noticing in your body? What are you noticing in your mind? And what are you noticing interpersonally? Identify in which domain signs of burnout or stress might be present.

Newman and Shapiro identified various techniques for coping:

Physical Techniques

- Take a breath. When we are stressed we forget to breathe, and a powerful tool to reduce stress might be taking several deep and slow breaths from your belly.

- Place your feet on the ground and feel connected to the ground.

- Take small breaks every hour.

- Stretch and relax your tense muscles.

- Take a walk and do regular exercise.

- If possible, take a power nap.

- Distract yourself with something very absorbing.

Psychological Techniques

- Be aware of your thoughts and what you are saying to yourself, and identify negative or pessimistic thoughts.

- Focus your thoughts on the things that are going well.

- Load your phone with pictures that inspire you and look at them.

- Play a song for three minutes that makes you happy.

- Think of something humorous.

- Imagine something beautiful, like a scene or landscape, or a safe place in your mind.

- Count something, such as the number of red objects in your room.

- Invoke visual protective equipment, such as imagining a mental seatbelt or an invisible shield from which your pressures bounce off.

- Write in a journal.

- Be aware of your vulnerabilities.

- Be aware of your signature strengths.

Social Techniques

- Make a quick phone call or write a text to a friend.

- Talk to a colleague.

- Plan something fun.

- Play with your children or pet.

- Think of when you’ve experienced support from a colleague.

- Give social support. Reaching out to someone who needs help may sometimes be the best way to help yourself.

“Structuring your involvement with your colleagues on a team or creating an informal team of colleagues with whom you check in periodically is really crucial to social support,” said Shapiro. “Some newsrooms have created buddy systems, and we can do this informally too.”

Also, it’s important to keep in mind what you have control over and what you don’t, he added. If you have control over it, act; if you don’t, ask yourself what you can do to improve your emotional response. If you are prone to worrying about things, even chronically, control this reaction by setting aside one hour each day specifically to worry about things, but make the effort of not engaging in worrying at any other time.

These tools require practice to make them effective, and if you are suffering from severe trauma symptoms, consult a therapist. The Dart Center has resources for journalists worldwide, in various languages, including the Journalist Trauma Support Network, which offers referrals and resources, and a guide for journalists seeking therapy for personal or work-related issues.

Other Resources

- Dart Center website

- If you are going to engage in assignments that may prove traumatic, the Dart Center’s “Self-Care Tips for News Media Before/During/After a Potentially Traumatic Assignment” can help prepare you.

- Elana Newman and Naseem S. Miller, senior health editor for The Journalist’s Resource, assembled a list of resources for coping with trauma as part of the Investigative Reporters and Editors Conference in June 2021.

- GIJN’s “How Journalists Can Prepare for Online Harassment, Disinformation” offers tools to deal with the stress of online harassment.

- Bruce Shapiro also recommends the online resource Troll Busters, for journalists who are victims of online harassment.