Double Exposure Film Fest Showcases Documentary Tradecraft

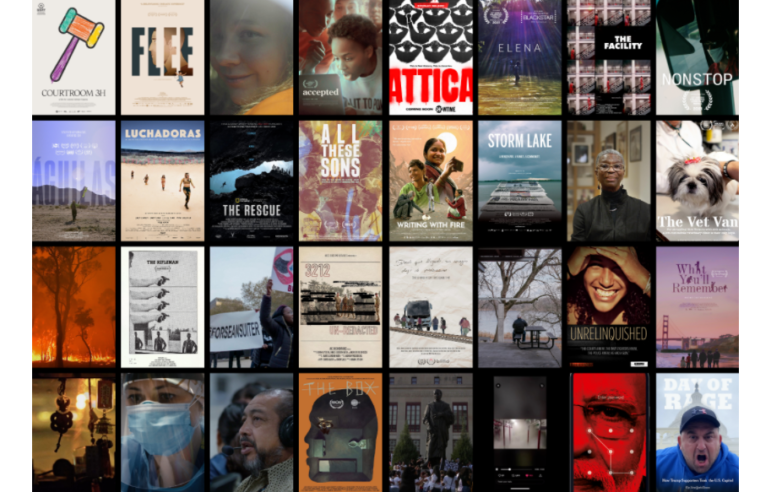

When 32 outstanding investigative documentaries were showcased at the Double Exposure Film Festival in the US last week — presented by GIJN member 100Reporters — one common question for attendees was this: How on Earth did the filmmakers persuade all these people to let their video cameras in?

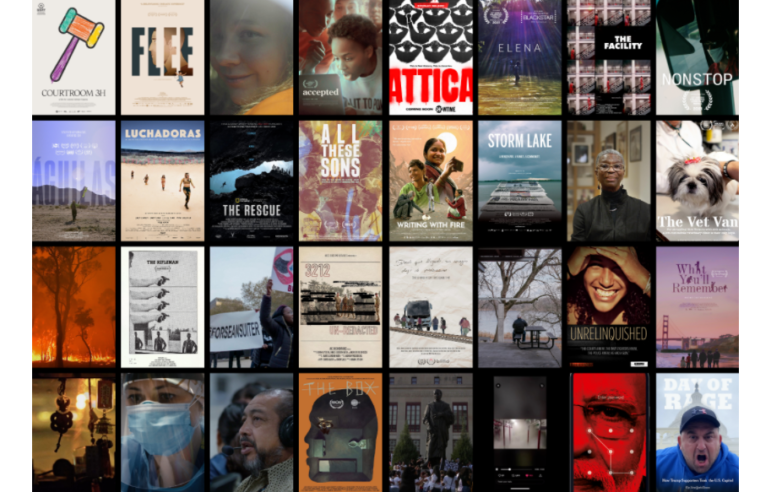

After all, it’s hard enough just getting off-record comments from sensitive sources when you have nothing but a notebook in your hand. Yet some of the featured filmmakers were able to film for extended periods in immigration detention centers, a New York COVID-19 intensive care unit, and otherwise sealed family court trials, while another team persuaded Thailand’s Navy SEALs to release their own rescue footage from the cave where 12 Thai children were trapped in 2018. The five-day event was bookended by premiere screenings of “United States vs. Reality Winner” — which tells the story of a US intelligence agency whistleblower — and “Accepted,” which delves deep into US college admission policies. The documentary “Writing with Fire,” created by filmmakers Rintu Thomas and Sushmit Ghosh, was also recognized for profiling the courage and impact of “low caste” women journalists in India.

“Writing with Fire” was celebrated at the DX Festival for unearthing the courage and impact of “low caste” women journalists in India. Image: Screenshot

All 32 documentaries are listed here.

In addition to more than two dozen separate discussions about the technical, ethical, and legal challenges facing investigative filmmakers, that central question about camera access was answered by a panel in a parallel, virtual festival event, the DX Symposium.

In this session, titled “Filming the Near Impossible,” filmmakers behind four of the featured documentaries — “The Rescue,” “The First Wave,” “The Facility,” and “Courtroom 3H” — described a wide variety of access strategies with one attribute in common: the trust of their subjects.

Access Strategies from Three Filmmakers

Seth Wessler — an investigative reporter at ProPublica — revealed that a webcam app activated by detainees inside a detention center in the US state of Georgia was the key access tool for “The Facility,” his exposé on the COVID-19 crisis facing immigrant detainees. He said funding proved important for the project, as the app charges 25 cents per minute for video calls, and he needed the service to run for hundreds of hours in 2020 to explain the life-and-death plight of ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) detainees.

Producers Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin, having previously documented real-time events in the Oscar-winning mountaineering documentary “Free Solo,” faced the new challenge of documenting a past event in their exploration of the 2018 cave rescue of a Thai youth soccer team. In addition, their film “The Rescue” was limited by COVID-19 restrictions, and lacked any interviews with the child survivors, as a “life rights” agreement for their personal stories had been already acquired by another studio.

Instead — having learned that crucial footage of the drama was held by Thailand’s Navy SEALs — the team slowly built relationships with officers from that unit in a series of video calls for more than a year.

“But we couldn’t get this footage just negotiating via Zoom,” said Chin. “So Chai had to fly [to Thailand] and quarantine and meet them in person. It just showed how you need that human connection.”

Vasarhelyi and Chin also convinced the international cave rescue team to reenact their rescue, moment by moment, and included some of this footage in their film.

Responding to a question on ethical deal-making with sources, Vasarhelyi said accepting reasonable conditions — and seeking permissions — from sensitive participants was generally a journalistic price worth paying to tell important truths, as long as filmmakers are transparent about their choices.

“I have a friend who made a very important film, and who never got permission from the participants — and that film still sits in the corner of their office,” she warns. “So we never film until we have a (legal) release form signed, period — and that’s how I’ve made seven out of eight films.”

But Vasarhelyi said the Thai Navy SEALs cave footage was so important that, for the first time, she had to agree to several specific conditions from a source — such as blurring all Seal members’ faces, agreeing not to share the footage through internet channels, and contractual stipulations about factual accuracy.

“That becomes more fuzzy — what is factual accuracy when you have 3,000 people on the ground, all experiencing events from their own point of view?” she said. “Look, (the negotiations) were incredibly difficult, and I won’t say I recommend it. But we were confident that everyone would understand that our intentions were right.”

The session also revealed that filmmakers can take advantage of built-in trust, in which sources know and respect previous quality investigations. For instance, Matt Heineman — whose prior projects include the Oscar-nominated “Cartel Land,” which revealed a vigilante resistance to Mexico’s drug cartels — explained that a connection from a previous documentary helped arrange four months of access to an intensive care unit in New York City, for his film “The First Wave.” He said this personal contact proved crucial, as he had previously “reached out to nearly every hospital system in the US for access,” without success. While the filming was initially restricted to medical staff, he said individual trust relationships developed so that the team’s cameras could follow the stories of two patients as well. Here, Heineman secured perhaps the most difficult kind of permission: agreement from grieving families to show the last living moments of COVID-19 patients.

“Of course there are HIPAA [US medical privacy] rules, but there was a lot of gray area we were treading, and I think we all felt this moral obligation to show what was happening inside our hospitals, because no one was really seeing it,” said Heineman. “If people really saw what was happening at that early stage on a greater level, would that have changed the eventual trajectory of the disease?”

Tips for Video Access

Some of the panel’s tips for gaining video access included:

- Be persistent and patient in asking for access — and try to make the most important access requests in person.

- If filming on site is impossible, seek creative alternatives — such as webcam apps, staff-carried GoPro cameras, social media video, or footage held by institutions.

- Try to get your principal subjects to sign a basic consent release form for the project — but invest time to develop a relationship with them before offering them the legal paperwork.

- If you’re restricted to video streaming while trying to develop relationships with potential participants, build rapport by turning some of the interviews into longer hangouts, with the record function switched off, and chat about issues unrelated to the investigation.

- Don’t make any agreements that would allow sources to vet film content, but be open, where reasonable, to a subject’s conditions about the filming process — such as a COVID-19 ward doctor allowing a video reporter to show a patient’s feet, but not their face.

- Ensure that the needs of the film do not trump the needs of the participants.

- Don’t pay for comment or cooperation, but be open to paying participants standard rates for material work done, such as freelance footage previously shot.

- If you decide to protect the identity of certain subjects by not showing their faces, then re-watch the whole documentary for any risks of the “mosaic effect” — where viewers can piece together a person’s identity from different scenes and event timelines.

Vasarhelyi said documentaries also have the storytelling power to unearth the highest standards in human behavior among private citizens, and can serve as a useful contrast to the illegal or unethical behavior by public officials that journalists often reveal.

“These films tend to be personal, and, for us, it has to move the dial [for society] in some way — to make the world just a little bit better,” she explained. “‘The Rescue’ is really about how all these people from very different walks of life came together to achieve the impossible. Just ordinary people — a retired fireman; electricians — who risked everything to save 13 souls they’d never met. Films like these invite us to be more generous in our own lives.”

Additional Resources

DIG Festival Honors Investigative Films That Exposed Scandals

Double Exposure 2020: 5 Investigative Documentaries to Watch

What To Watch: 5 Anti-Corruption Documentaries from Films for Transparency

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.