14 Independent News Sites Changing Cuban Journalism

Between 2001 and 2017, 14 media organizations were launched in Cuba that are already making an impact on and off the island. Most of their teams have fewer than a dozen journalists and many of them are volunteers. All these media sites have reporters working from Havana, but 50 percent have offices or newsrooms in foreign cities, such as Miami, Mexico City and Valencia in Spain.

The sites cover a broad range of topics: politics, society, the environment, the economy, technology, culture and sports. Most of them have received threats or have been harassed by fake social media accounts. While some have solid business models, others haven’t even started thinking about how to generate revenue. Their audiences are scattered around the internet and include Cubans living on the island with infrequent online access (available almost exclusively in public spaces), Cubans living in the diaspora and foreigners who want to learn about Cuba.

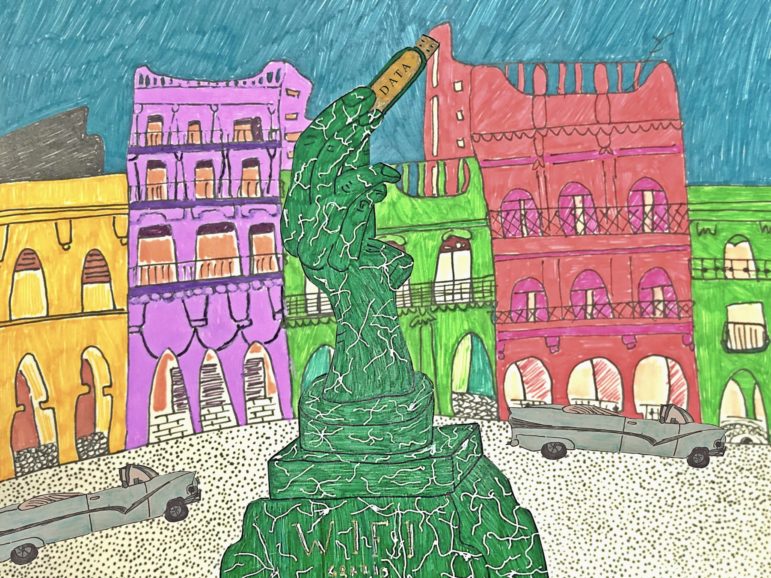

These media organizations innovate without realizing they are being innovative. They develop applications to download content offline, raise funds in a kind of “Creole” crowdfunding system that flouts national laws and the US blockade of the island, produce podcasts and create partnerships.

Almost all of them survive in an openly illegal terrain known as “allegality.” Non-state media in Cuba defy the very constitution of the country, which explicitly prohibits the existence of private media in Article 52.

They have won international awards and recognition, which endorses the quality of their content. For example, in 2017, El Estornudo’s Jorge Carrasco became the first Cuban journalist to receive the Gabriel García Márquez Journalism Award and the Postdata team was a finalist in the Data Journalism Awards.

These publications have caused such a stir that, at a meeting with officials of the Cuban Communist Party in early 2017, the vice president reportedly said: “The OnCuba digital platform is very aggressive toward the Revolution and we are going to shut it down. If they want to make a scene, so be it. Let them say we are censors.”

An analysis of the 14 non-state media in Cuba shows they all have one thing in common: their primary goal is journalism. They are: Periodismo de Barrio (2015), Cachivache Media (2016-2017), 14ymedio (2014), Cibercuba (2014), El Estornudo (2016), Diario de Cuba (2009), El Toque (2014), Hypermedia Magazine (2016), La Joven Cuba (2010), Negolution (2016), OnCuba (2012), PlayOff (2015), Postdata (2016) and Progreso Semanal (2001).

Almost all of them were launched after 2014. Seventy percent of non-state media in Cuba were created between 2014 and 2016, meaning they only have three years of experience. But many of those ventures have received recognition from international journalism organizations such as the Gabriel García Márquez Foundation for a New Ibero-American Journalism, and their work has been published by larger media groups, including Univision and Internazionale magazine in Italy.

All of them focus on national issues, while only 35 percent also cover stories in the Cuban provinces and 21 percent cover local news. Eighty-five percent address social issues, followed by culture (57 percent), politics (50 percent), sports (42 percent) and the economy (35 percent). Some specialize in specific niches, such as the environment (Periodismo de Barrio), technology (Cachivache Media), entrepreneurship (El Toque), business (Negolution) and sports (PlayOff). For the rest of the publications, coverage is usually more general.

Who Is Creating Cuba’s Emerging Media?

Young people. Teams. Women. Thirty percent of Cuba’s independent media organizations were founded by one person, while the other 70 percent were launched by two to eight journalists. Such is the case with 14ymedio, El Estornudo, PlayOff, Cachivache Media and Postdata, among others. Following a regional trend, more than 40 percent of the founders are women.

Fifty-eight percent of the founders are journalism and social communication graduates and five of them have pursued graduate studies. Most of the executive and editorial management positions are held by men, and all of their managers are journalists, except at CiberCuba, PlayOff and La Joven Cuba.

Who Is Reading? From Where?

The audiences of the digital publications we studied vary significantly. There are sites with fewer than 4,000 unique users per month, while others that have more than 4 million. It is notable that some of the audiences overlap, such as CiberCuba or general information outlets OnCuba and 14ymedio.

For the remainder, which tend to produce long-form, specialized content for a specific niche, attracting new users does not seem to be a priority.

It’s also important to note that these numbers are for website traffic, but they do not reflect the total number of users. Due to limited internet access on the island, traffic is often generated through other means, including emails, PDF magazines published offline, or in the so-called Paquete de la Semana (a weekly package of digital news and entertainment that is distributed via USB drives throughout Cuba).

Although their content is aimed at Cubans living on the island, only 41 percent of these sites succeed in having residents of Cuba as their main source of traffic. For 50 percent of these organizations, the majority of readers come from the United States, specifically the Cuban diaspora residing in Miami.

As for the second country of origin, users vary between Venezuela, Uruguay and Spain, while the third is further diversified and includes Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, etc.

Traffic from mobile devices continues to rise among non-state media in Cuba. CiberCuba, which is blocked on the island, reaches 70 to 79 percent of its audience via mobile devices and Facebook Instant Articles, which made it more accessible to users of the social network living in the country.

Based on our observations, Facebook is the most-used social network by these media organizations. All of them use Facebook, followed by Twitter (92 percent), YouTube (78 percent) and Instagram (57 percent). None of them use apps that require a more consistent connection to the internet, such as Snapchat, Telegram or WhatsApp.

Social media strategies vary from publication to publication. In 14ymedio’s case, its founder, Yoani Sánchez, had more than 700,000 Twitter followers when she launched the site, which is why it focuses on social media as the main way to bring traffic to the site.

El Estornudo has developed exclusive social media profiles where it publishes daily. “Píldoras,” for example, is a photo gallery accompanied by short stories about ordinary people living in Havana and Miami. It also has a weekly section where it publishes illustrations and animations by Cuban designers.

Periodismo de Barrio (a site founded by the writer of this report) added a part-time journalist to the team in 2017 to develop its social media strategy. Among its most successful innovations is the publication of more than 10 photographs on Instagram every week, and the way it has adapted 10 stories into slideshows that are less than three-minutes long.

Three of the media organizations have mobile apps. CiberCuba has the most impressive statistics, with approximately 100,000 downloads and 30,000 regular users per month. Because its website is blocked, the app is the main access point for local users.

How Relevant Is the Content?

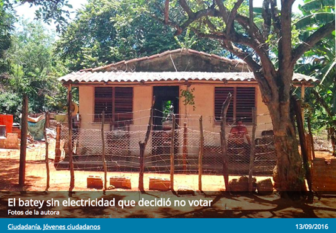

“The locals say that the Los Danieles batey [a Cuban word for settlement] is so intricate that not even the thieves approach it. It is so far off in the country, so isolated, that the electric system does not reach it.” That’s how a September 2016 article published on digital magazine El Toque begins.

In 2012, just before the local elections, the residents of this community decided not to vote; in previous elections, only six people from the 18 families who live there participated. El Toque’s piece attracted a lot of attention from readers living in Cuba, highlighting the importance of telling local stories with national significance.

Cuba is often perceived as an island with limited access to the internet and a state media system that leaves no room for dissent. However, the emergence of the sites mentioned in this story demonstrates that the national media ecosystem is more complex and diverse than many think.

Despite all the limitations they face, the new media launched between 2001 and 2017 are innovative and have an impact. Some of the most significant successes in recent years have been:

- Covering issues omitted or under-reported in the national press.

- Experimenting with new genres and formats.

- Diversifying content distribution spaces.

- Establishing alliances with other national and international media.

- Winning awards and other recognition from institutions, organizations, companies and international governments.

For example, El Estornudo focuses on two main issues: the Cuban exodus to the United States – the migratory route through Central America, the immigrants stranded in Panama or Costa Rica and the border crossings through Mexico – and the living conditions in certain neighborhoods of Havana, marginal areas where rural migrants gather, people who the state does not recognize or register in the census, as well as the forced deportation of those same migrants.

Hypermedia magazine has recruited important Cuban intellectuals from the diaspora to contribute to the magazine, including Rafael Rojas and Gustavo Pérez Firmat (named one of the most influential Latinos in the United States in 2004), increasing its prestige.

Postdata has employed gamification techniques to report on Cuban cinema. In an issue dedicated to cinema, it developed a trivia game that allowed users to test their knowledge.

The stories that have had the most impact in Negolution are those related to social ventures that go beyond profit and have a positive impact on the community. Through these stories, Negolution has attracted contributions from inside and outside Cuba and increased social awareness on topics such as recycling, hiring, the benefits and treatment of workers, the relationship with the communities where the projects are developed, and corporate social responsibility.

In 2010, Cuban intellectual Esteban Morales separated from the Communist Party of Cuba after publicly voicing his concerns about corruption in the country. La Joven Cuba was one of the sites that published articles on the topic and has since conducted several interviews with Morales. In 2012, it organized a National Meeting of Cuban Bloggers that addressed issues related to internet access and the right to free expression on social media and blogs. Shortly after, the La Joven Cuba site was blocked at the University of Matanzas. In 2013, the block was lifted.

Among its products, Cachivache Media created El Trastero, a podcast which already has more than 30 episodes and is available on iTunes and Soundcloud.

Among its products, Cachivache Media created El Trastero, a podcast which already has more than 30 episodes and is available on iTunes and Soundcloud.

One of 14ymedio’s most important challenges came on March 20, 2016, when US President Barack Obama visited the island. For the first time, an independent Cuban media outlet was accredited by the White House to cover part of the visit – an important step that brought 14ymedio global recognition.

In May 2016, Mónica Baró, from Periodismo de Barrio, took part in a workshop on covering water issues which was organized by the Gabriel García Márquez Foundation. Following the workshop, more than 33 short stories were written by 26 journalists from 13 Cuban provinces. The series included illustrations and provided job opportunities for four designers and 26 journalists.

Dangers, Threats and Misconceptions

Almost all of these emerging Cuban media groups have been the target of threats and other forms of harassment. Some journalists based in Cuba have been interrogated by the Department of State Security and others have been harassed on social media by fake or anonymous profiles and pages.

At the end of December 2014, 14ymedio reported that several members of its team had been arrested. Reinaldo Escobar was arrested when he left the building and was handcuffed and taken to a patrol car waiting nearby; 14ymedio reporter Víctor Ariel González was also arrested. The day before, an officer had arrived at journalist Luz Escobar’s home to warn her not to go to Plaza de la Revolución where the artist Tania Bruguera had planned an event demanding freedom of expression. That same day, the editor of the publication, Yoani Sánchez, was placed under house arrest.

The lack of legal recognition hinders journalism in Cuba. On October 11, 2016, six members of Periodismo de Barrio (including the author of this article and two of our contributors) were arrested in the municipality of Baracoa, Guantánamo.

As reported on Periodismo de Barrio, the rationale for the arrests was that in Baracoa, Maisi and Imias, reporting activities could not be carried out because those areas were under a state of emergency. We were interrogated and our equipment was seized. A later review of the Cuban legislation revealed that no such state of emergency had been declared. However, all journalists were forced to leave the territory.

Around the same time, Maykel González Vivero, a contributor to El Estornudo, was detained by Cuban government authorities for 72 hours. They confiscated his laptop and the rest of his equipment. A year later, during his coverage of Hurricane Irma, he was arrested again and he recently reported being a victim of “humiliating procedures” in an article published by Diario de Cuba, where he also works.

Reporter Sol García Basulto was arrested on the night of November 4, 2017, by state security forces when she was traveling to Havana. A Camagüey correspondent for 14ymedio, she was intercepted during the trip to the capital by officers who handcuffed her and confiscated her belongings. She was released at about two in the morning, and warned that she could not leave the province for 60 days.

As reported in this story, García Basulto was detained while she was traveling to Havana to visit 14ymedio’s newsroom to begin filing the paperwork necessary to travel abroad. The reporter was going to apply for a visa at the consulate of Panama to take part in an investigative journalism course at the invitation of the Latin American Journalism Center.

In the last months of 2017, Harold Cárdenas, one of the editors of La Joven Cuba, was subjected to intense online campaigns to discredit him, mostly by anonymous users. In addition, several journalists who contribute to both emerging and state media have been dismissed or sanctioned.

Innovation, Awards and Recognition

Despite the technical and operational challenges faced by journalists launching new media initiatives on the island, they are winning recognition from renowned international institutions.

El Estornudo won the 2017 Gabriel García Márquez Award in the text category for Jorge Carrasco’s work entitled “The Story of a Pariah,” which tells the story of Havana’s “most famous transvestite.” When Distintas Latitudes published the 25 most interesting journalism pieces of the year 2016, four stories by El Estornudo appeared on the list. Its editorial director, Carlos Manuel Álvarez, received the fifth edition of the “Nuevas Plumas” narrative journalism award for his piece “The Noble Beasts,” also published in El Estornudo.

During its first year, Periodismo de Barrio was recognized in important international competitions. The story “La mudanza,” by Mónica Baró, was one of three finalists in the text category of the 2016 Gabriel García Márquez Award. Elaine Díaz, director of Periodismo de Barrio, and author of this report, received a scholarship from the Earth Journalism Network to cover the United Nations Conference on Biodiversity, held in December 2016 in Cancún, Mexico. This enabled the publication to further its coverage of environmental issues at the regional level and to establish a working link with Peru’s La Mula.

CiberCuba has been a pioneer in social media publishing through Facebook Live, Messenger and Instant Articles. Postdata has formed an innovation team where journalists and data analysts work together for the first time.

The team at Diario de Cuba has developed a space for geo-referenced data journalism, with a focus on particularly sensitive and current issues in Cuba. The results, which combine digital maps with data collected by journalists and contributors, not only answers the classic question of where the events are taking place, it also serves as a tool for analysis that contributes to freedom of information.

PlayOff is the second PDF magazine that has emerged in Cuba and is distributed in the weekly paquete of digital news distributed via USB drive.

Among this group of independent digital media, several interesting initiatives are worth mentioning, including international alliances such as the one that El Estornudo has formed with the Spanish publication, Contexto, and The Huffington Post, where it publishes a weekly column. Periodismo de Barrio has a similar alliance with Global Voices.

This post first appeared in Spanish on SembraMedia and was translated into English by IJNet. The English version is cross-posted here with permission.

Elaine Díaz is SembraMedia’s Cuban ambassador and the founder and director of Periodismo de Barrio, which in March became GIJN’s first member organization in Cuba. Díaz is the first Cuban to receive a Nieman Fellowship at Harvard and was a professor at the University of Havana from 2008 to 2015.

Elaine Díaz is SembraMedia’s Cuban ambassador and the founder and director of Periodismo de Barrio, which in March became GIJN’s first member organization in Cuba. Díaz is the first Cuban to receive a Nieman Fellowship at Harvard and was a professor at the University of Havana from 2008 to 2015.