Investigative Journalism in China: Challenge, Risk, and Opportunity

If you put “investigative journalism + China” in a Google search bar, you’ll probably be disappointed with the few results it returns. There is a book about the topic, “Investigative Journalism in China: Eight Cases in Chinese Watchdog Journalism,” which I read a few years ago and would still recommend. For the English-reading world, there is really limited information about this important topic. Even if your Chinese is good enough to perform a search, you will again be surprised about how few relevant results you get.

If you put “investigative journalism + China” in a Google search bar, you’ll probably be disappointed with the few results it returns. There is a book about the topic, “Investigative Journalism in China: Eight Cases in Chinese Watchdog Journalism,” which I read a few years ago and would still recommend. For the English-reading world, there is really limited information about this important topic. Even if your Chinese is good enough to perform a search, you will again be surprised about how few relevant results you get.

This is not an indication that investigative journalism is dead in China. But it is indeed declining – check out an article I wrote for IJNet back in 2011 (China’s Next Brain Drain: Investigative Journalists) or a more recent one on the same topic in 2013 (中国第一代调查记者“触顶”转型). My friends who used to work as investigative journalists in China have been flocking to other industries. Many started their own businesses (check out these articles in Chinese 亚洲周刊|胡泳:新媒體創業風起雲湧爭奪話語權, published earlier this year). Some have turned to non-profits (Deng Fei for example). And some have just retired to open their guesthouses and enjoy life.

For those who stay and continue to fight, however, China remains a gold mine for investigative stories, with lots of pressing issues – an environmental crisis, government/Party corruption, judicial injustice, public health, and money laundering (see the cases of Bank of China and UnionPay), among others. New technologies and powerful social media, meanwhile, are providing new opportunities and helping stories reach a broader audience and achieve greater social impact.

A recent example is an investigative documentary about air pollution by Ms. Chai Jing, a former reporter for China Central Television (CCTV). She quit her job, led a team, spent 1 million RMB (around US$160,000) and made this film, basically trying to answer three questions: What is the pollutant PM2.5? Where does it come from? How can China solve its pollution problem? You can watch the film here – with English subtitles (crowdsourced by Chinese watchers and led by a high-school final-year student):

The video, entitled Under the Dome, went viral since it launched on March 1, 2015. Within 3 days, it reached 200 million hits. It is a TED-style talk, mixed with traditional TV interviews with credible sources, international reporting (she went to the UK and US to learn from the experience and practice in London and Los Angeles), drone shooting of polluting factories (which failed because the pollution was too serious), data and charts as an effort to make sense of abstract numbers, social network visualization of the corruption within the environment and energy power system, and even animation to illustrate how PM2.5, a harmful micro-particle in pollutants, can invade human bodies and cause irreversible harm.

The video is not perfect – lots of public debate has centered around the way it tells the story and marshals facts and data — but it successfully leveraged multiple technologies and presentation formats now available to make an extraordinarily powerful film.

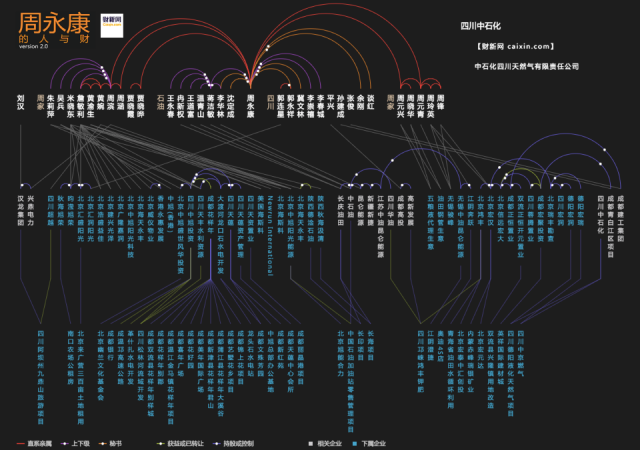

Another example is a series of stories around Zhou Yongkang, the most senior Chinese Communist Party official caught in the anti-corruption campaign last year. Carried out by a nine-person team at Caixin magazine, one of the most reputable media organizations in China, the investigation took one year and produced a 60,000-word piece, portions of which are translated into English.

Another example is a series of stories around Zhou Yongkang, the most senior Chinese Communist Party official caught in the anti-corruption campaign last year. Carried out by a nine-person team at Caixin magazine, one of the most reputable media organizations in China, the investigation took one year and produced a 60,000-word piece, portions of which are translated into English.

It is solid reporting, but how many people will sit down and read through 60,000 words? So Caixin’s Data Visualization Lab produced an interactive visualization to illustrate the people and companies connected with Zhou. (There’s an English version here, but note that it’s designed differently from the Chinese version below.) This project received 4 million hits, according to Huang Zhimin, the CTO of Caixin and head of its Data Visualization Lab.

In other cases, investigations are not done by professional journalists or media organizations, but by ordinary citizens. Interestingly, you don’t hear the term “citizen journalism” in China now, at least not as much as you would a few years ago. But that doesn’t mean citizen journalism is dead. Quite the opposite – with the popularity of social media, everyone provides information and the pieces can quickly come together. A well-known example is the 2012 case of the “watch brother,” a local official whose photos of wearing luxury watches were spotted by social media detectives, who identified all the brands (Bulgari, Omega and Rolex, to name a few) and even some of the models. The official was later investigated and sent to jail for 14 years.

Under the Dome was taken down from Chinese video platforms after surviving online for only 7 days. However, an app about pollution that was mentioned in the documentary hit number one in the app store and reached 3 million users. It not only takes data from the Ministry of Environment and makes it more readable, but also has a crowdsourcing function where users can report factories that are disposing pollutants. By March, more than 300 factories had been reported and had to change their behavior.

Under the Dome was taken down from Chinese video platforms after surviving online for only 7 days. However, an app about pollution that was mentioned in the documentary hit number one in the app store and reached 3 million users. It not only takes data from the Ministry of Environment and makes it more readable, but also has a crowdsourcing function where users can report factories that are disposing pollutants. By March, more than 300 factories had been reported and had to change their behavior.

Changes are happening in Chinese investigative journalism, with the help of more open data and better tools. There are still lots of challenges and risks for doing serious in-depth journalism in China. Censorship is exercised online and offline. Surveillance is by default, internal and external. Media institutions are declining, much as everywhere else in the world. Yet despite of all the difficulties, continuous efforts are being made – always as a collaboration among media organizations, civil society, and individual citizens. And it’s important to keep it going.

Yolanda Ma is the co-founder and editor of Data Journalism China, an independent website that promotes and educates on data journalism in Chinese. She has trained hundreds of professional journalists in China on data analysis and visualization skills since 2012. She also consults for the U.N. on innovation and communications. She previously worked for Reuters and the South China Morning Post in Hong Kong, and is currently based in Bangkok.

Yolanda Ma is the co-founder and editor of Data Journalism China, an independent website that promotes and educates on data journalism in Chinese. She has trained hundreds of professional journalists in China on data analysis and visualization skills since 2012. She also consults for the U.N. on innovation and communications. She previously worked for Reuters and the South China Morning Post in Hong Kong, and is currently based in Bangkok.