Death of a Prosecutor: 40,000 Audio Recordings, Two Years, One Team

Editor’s note: Following is the inside story of how Argentina’s La Nación Data team uncovered new leads from digging into leaked recordings collected by prosecutor Alberto Nisman, who was murdered while probing a Buenos Aires terrorist attack. The reporters pored over 40,000 audio recordings with a closed group of 120 volunteers over two years to reveal new and important information within the recordings.

I. Introduction

Here’s how and why we built a database of 40,000 phone interceptions, with a closed network of 120 collaborators, to publish a news app of 200 selected audios.

With the judicial trial reopening in December 2016, there is more to come and more to support this effort to hear and classify 100 percent of the audios.

II. A Terrorist Attack, the Jewish Community, the Iranian Government, a President Accused and a Dead Prosecutor

Argentina, July 1994. A massive bomb explodes in front of the AMIA, a Jewish center in Buenos Aires. The attack kills 85 people and injures 300.

After a long investigation, in 2006, a judge orders an international arrest warrant for the accused, most of them members of the Iranian government.

After a long investigation, in 2006, a judge orders an international arrest warrant for the accused, most of them members of the Iranian government.

Immediately, Interpol issues red notices to assist the national police forces. The Argentinian government repeatedly demands that the accused be put on trial, but Iran refuses to comply.

Then, in January 2013, the Argentinian demand for justice takes an unexpected turn during Cristina Kirchner’s presidency, when a memorandum of understanding is signed with Iran to jointly investigate the attack.

The prospect of working with Iran when those accused in the attack were members of the Iranian government creates huge public controversy and disputes in the Argentinian Congress.

In January of 2015, Alberto Nisman, the special prosecutor investigating the terrorist attack, charges Kirchner and other Argentinian authorities with orchestrating a criminal plan with Iran. Nisman claims that the Argentinian government intended to cancel the Interpol red notices and guarantee the innocence of the Iranian accused, with the objective of restoring commercial relationships with Iran.

Three days after making public his accusation and hours before Nisman is due to testify in Congress, he is found dead in his apartment. Some claim he committed suicide, while others say it was clearly murder and march through the streets demanding justice. This march was called the “March of Silence.” The court has yet to decide, but for two years, Nisman’s case has gripped Argentina.

Three days after making public his accusation and hours before Nisman is due to testify in Congress, he is found dead in his apartment. Some claim he committed suicide, while others say it was clearly murder and march through the streets demanding justice. This march was called the “March of Silence.” The court has yet to decide, but for two years, Nisman’s case has gripped Argentina.

Nisman’s accusation about the AMIA attack was dismissed multiple times by different judges during Kirchner’s presidency. Finally, in December of 2016, with new president Mauricio Macri in power, the case was reopened.

The main evidence that Nisman had collected to support his accusation were thousands of audio recordings from a tapped phone. Exactly 40,354.

III. The Collaborative Investigation

The evidence leaked and several media outlets published the whole database or some individual recordings.

But at La Nación Data, we decided to combine technology and collaborative work, and take on the classification and analysis of every single audio in order to produce complete stories with a combination of audios that could help boost the credibility of the prosecutor’s hypothesis, put them in context, or to find and tell new stories.

But at La Nación Data, we decided to combine technology and collaborative work, and take on the classification and analysis of every single audio in order to produce complete stories with a combination of audios that could help boost the credibility of the prosecutor’s hypothesis, put them in context, or to find and tell new stories.

First, we tried using machine-learning techniques and voice analytics without any success.

So we chose to rely on VozData platform, an open source web app that La Nación developed with the support of Open News and Civicus Alliance. (Open Source: Crowdata.)

So we chose to rely on VozData platform, an open source web app that La Nación developed with the support of Open News and Civicus Alliance. (Open Source: Crowdata.)

We uploaded the audios in two phases, and users started listening and organizing them based on established categories.

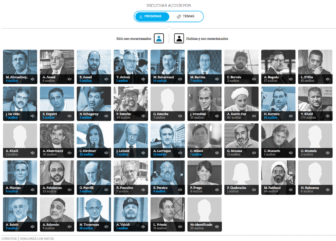

All in all, the entire project involved two years of classification and more than 120 trusted, closed network volunteers from different universities, NGOs, countries and backgrounds.

Most of the work was done remotely. But we also encouraged the users to participate in four civic marathons that were held at La Nación, which we called Audiothons, hoping to share knowledge about the case and to analyze thousands of new recordings.

IV. Analysis

Once the initial classifying phase was complete, we had a shortlist of more than 2,000 audios and we had to listen again this shortlist and select those that included new findings or that gave context to Nisman’s selected ones. This was done by the data team. We started investigating the database using filters for specific words in text typed by collaborators inside categories, like tags and additional information.

Once the initial classifying phase was complete, we had a shortlist of more than 2,000 audios and we had to listen again this shortlist and select those that included new findings or that gave context to Nisman’s selected ones. This was done by the data team. We started investigating the database using filters for specific words in text typed by collaborators inside categories, like tags and additional information.

The 40,000 audio tapes corresponded to calls made in the four tapped telephones of Yusuff Khalil, an Iranian agent in Buenos Aires.

Only 10 percent of the tapes contained metadata identifying the origin telephone number and the destination telephone number of the calls, and also the data of the cell which detected them, if it was a mobile phone.

The big challenge of this call screening task was to identify the voices of the people involved, when these people, due to any relationship between them, did not identify themselves, or when they called each other by nicknames. We then corresponded the phone number with a person, office, institution, etc. In our volunteer network and data team members, we had “specialists” on specific people so we would then pass any audio we had doubts about to them. So we found some of us were good “hearers” and could identify specific voices – a new skill useful for future audio cases.

Then we organized a telephone guide which included all the numbers as we identified them. The voices of some of the people who appeared more frequently in the media were easily recognized, but this was not so easy with the majority of the voices.

To simplify the task, on a spreadsheet, we filtered by destination phone number *2747 – the voicemail of the cell phone company – and, after listening to the messages left on the voicemail, we identified the origin phone number and the date and time. Some of the people involved in the phone calls identified themselves with first and last name when they left a voice message.

V. Major Findings

For the second anniversary of Nisman’s death, in January of 2017, we prepared a special scrollytelling feature that was published on all our platforms, including the TV channel.

For the second anniversary of Nisman’s death, in January of 2017, we prepared a special scrollytelling feature that was published on all our platforms, including the TV channel.

We produced four new front page stories revealing original information discovered within the audios. We also created an interactive app to navigate the recordings by both topic and person, and we received even more information from readers in a Google form where we asked for feedback.

Iran’s local community paid bails to help a local activist, leader of the Kirchner political movement “Quebracho.”

Iran’s local community paid bails to help a local activist, leader of the Kirchner political movement “Quebracho.”- A national senator from official government party was an active lobbyist for Iranian government, along with local businessmen.

- Anniversary package included analysis, an interactive timeline, app launch and behind the scenes information.

- Ex-National Army Chief General Cesar Milani is possibly related to an illegal espionage network.

- Iran financed a local activist movement leading pro-Kirchner government demonstrations in a march against the US Embassy.

VI. The App

From the original database we included almost 200 audios in an interactive news app that can be navigated by person or topic.

Whole audios were uploaded to avoid complaints that they were edited to reach conclusions; we highlighted the most relevant parts of the conversations to facilitate the listening.

Whole audios were uploaded to avoid complaints that they were edited to reach conclusions; we highlighted the most relevant parts of the conversations to facilitate the listening.

Each person and topic has an extended information link within the app.

To reuse the platform for future reporting regarding Nisman trial updates, any tag for person or topic can be embedded as a single playlist in an article.

VII. Technology

HTML; Javascript Isotope and Wavesurfer.js; Google Spreadsheets; Excel; Google Forms; and XMind.

VIII. Impact

The publications obtained wide reach on social media and among other news outlets.

The investigation was requested by Federal Judge Claudio Bonadio as evidence in the trial of ex-chancellor Héctor Timerman, who is accused of treason in the AMIA case.

The investigation was requested by Federal Judge Claudio Bonadio as evidence in the trial of ex-chancellor Héctor Timerman, who is accused of treason in the AMIA case.- The investigation received the attention of Argentinian Minister of Security Patricia Bullrich, who highlighted the proactive role of media to investigate in the absence of judicial commitment that had abandoned and dismissed the investigation.

- One of the stories on Iranians financing bail for a local activist was a trending topic in Argentina.

- Twenty-three readers also contacted us directly with more information about the audios through a Google form that we included in the app.

IX. Open data

We published the database in Google Spreadsheets, including audios, main text highlights, time stamps of the most important selections within the audio, descriptions of subjects and biographies.

X. Conclusion

What we’ve learned at La Nación Data is to never believe a project is impossible, no matter how large. The proof was there — 40,000 audio files — but everyone said this was impossible to process. So we said, why not?

If you believe in the power of a community that wants to help, just make it possible; facilitate with the right tools and offer some basic rules, call them and they will assist.

This is another case we hope inspires other media to use technology to serve a cause, and prove that real impact and change will come if we learn to collaborate .

Volunteers’ participation and close interaction closely with journalism, along with a very large dataset, produced knowledge. In this industry in which we differentiate through knowledge — not raw data — we can only become sustainable if we learn to open, change our self-centered mindsets, and ask for help.

This post first appeared on La Nacion’s blog and is reproduced here with permission. LNData is La Nacion‘s data team which focuses on special cases, data visualizations and creating databases and tools for journalism.